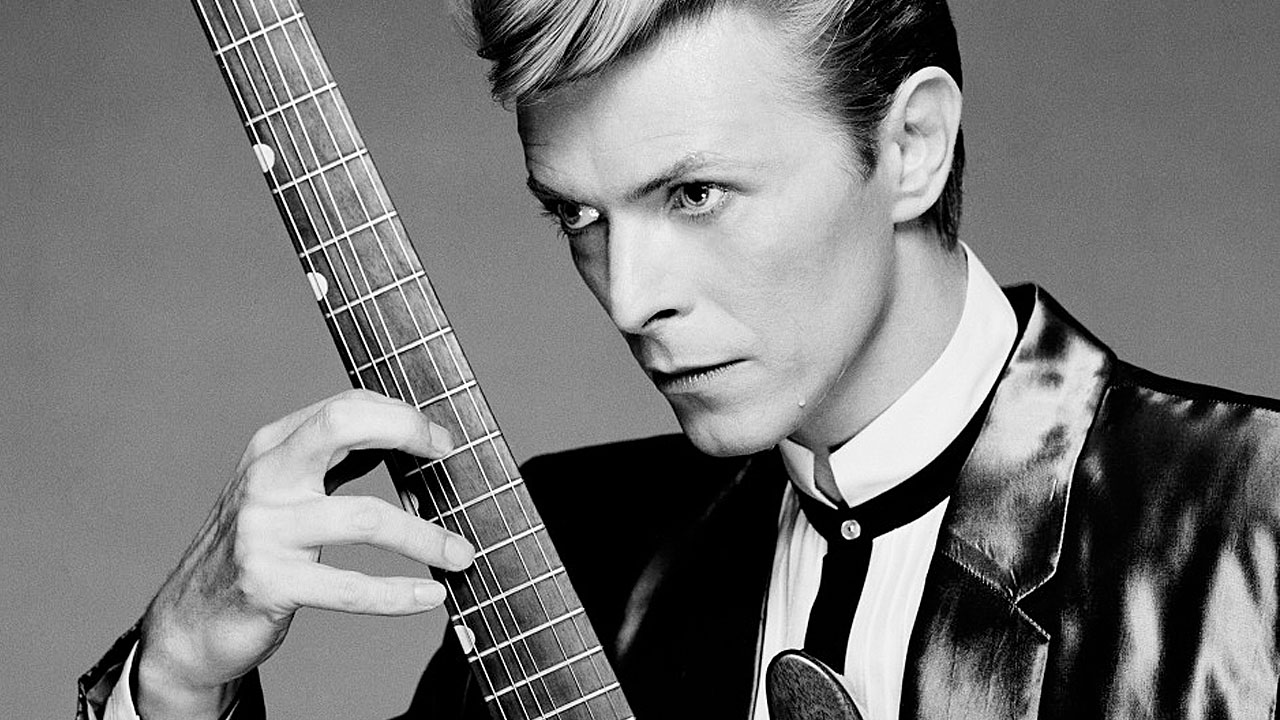

You have to hand it to David Bowie. He certainly knew how to be the party—and how to break up the party. On Sunday night, just as Hollywood celebrities were arriving at their post-Golden Globe awards events, the laughter reportedly died down and a hush fell across the revelers: Bowie was dead at 69 from cancer.

David Bowie turned toasts into conversations about memento mori.

His death stunned everybody. Just a month earlier, he had appeared at the opening of his off-Broadway show Lazarus, and, as always, he looked great. Three days earlier, he released his most ambitious record in recent memory—a progressive jazz tour de force. We had seen him in brand new music videos which bewildered us.

To the art world, he seemed transcendent. In film, he held multiple generations transfixed. To fans, he gave hope that you could always reinvent yourself, that you need not stay mired in the same role or life phase. In the cartoon The Venture Bros, he appeared simply as “The Sovereign,” a benevolent force for good working mysteriously behind the scenes of the cosmos. Arguably no celebrity meant this much to that many people since John Lennon.

Perhaps most of all, in death, Bowie taught us something about how to die. He did not make his fight with cancer a publicity spectacle. He died with dignity, in quiet, with his family.

To the Christian community, however, the early Bowie initially seemed to some like an existential threat. His gender-bending characters in the ’70s on albums like Hunky Dory and The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust had pastors and church leaders alarmed.

To Larry Norman—the Jesus Movement rock icon—Ziggy represented the lostness of the new generation of music. On Only Visiting this Planet, his album on MGM records recorded under the supervision of George Martin, Norman quipped, “Alice is a drag queen; Bowie’s somewhere in between. Other bands are lookin’ mean. Me, I’m trying to to stay clean. I don’t dig the radio. I hate what the charts pick. Rock & roll may not be dead, but it’s getting sick.”

Even the critically savvy British rock journalist Steve Turner, a Christian who had written profiles on Eric Clapton, Johnny Cash, and many others, saw nothing of permanence in Bowie’s work. He wrote in 1978: “I can’t see us humming Bowie tunes in 20 years or even 5 years’ time.”

In a piece written in 2013 entitled “The Hole in Bowie’s Soul,” Turner revisited that idea, advancing the thesis that Bowie’s legacy was about style, not substance. Unlike contemporaries like John Lennon, Bob Dylan, and Pete Townshend, Bowie stood for little more than selling himself. Politically and philosophically, Turner implies, The Thin White Duke was innocuous at best or horribly misguided at worst. Religiously, he dabbled early on in everything from the occult to Buddhism. Not good.

But such a harsh assessment of Bowie seems not in keeping with the actions of a man who, at a key turning point in history, rallied against totalitarianism. In 1987, Bowie returned to West Berlin, where he once lived and recorded some of his best work. With his back to the Berlin Wall, he belted out “Heroes” with his band, crying out for liberty to the crowd in German. Thousands of East Berliners pressed up against the other side of the wall to hear him, and they subsequently began vigorously protesting against the Communist regime.

The riots got the attention of the West, and one week later Ronald Reagan stood near that same place and uttered the now unforgettable words: “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall.” As he commented on the event some years later, it was clear the event moved Bowie, who remembered that “when we [played] ‘Heroes,’ it was really anthemic, almost like a prayer.”

On January 11, 2016, the German Foreign Office officially recognized Bowie’s contribution in helping bring down the wall.

For some reason, Bowie persisted in conventional God talk throughout his life. In the end, he revisited biblical themes in his work. Despite repeated reviews calling his music nihilistic, he responded, “I’m not quite an atheist, and it worries me.” Later, when paying tribute to his recently deceased friend Freddie Mercury, Bowie recited The Lord’s Prayer and told reporters, “I have an undying belief in God's existence. For me it is unquestionable.”

Something also changed for the star after he became a father. In an interview with NPR’s Renee Montagne in 2002, she noted that—could it possibly be?—he was singing on his then most recent record about the theme of hope? Bowie replied: “I think I have to imbue my songs with a certain sense of optimism now, more than I ever did before, because I have a child.” (Indeed, it’s exceedingly difficult to keep up one’s nihilism with a toddler running around the house.)

And then there is Blackstar, his final artistic statement, his “parting gift to fans,” a death notice, according to his longtime producer, Tony Visconti. His final single (and Broadway play) is entitled “Lazarus,” which, London’s Telegraph newspaper had to inform its readers, “refers to the biblical character who was raised from the dead four days after he died by Jesus.”

On two tracks, Bowie speaks of leaving his body and ascending to heaven, singing, after the manner of gospel hymnody, “just like that bluebird, oh I’ll be free. Ain’t that just like me?” So too, in heaven, he claims that he has scars that can no longer be seen—possibly indicating his belief in a continuity of his personhood before and after death.

And, finally, on the last track of his final record, we hear him seemingly do an about-face with respect to charges that his work was characterized by the “soulless” and “meaningless.” He says in his final goodbye, “I Can’t Give Everything Away”:

I know something is very wrong

The pulse returns the prodigal

The blackout hearts, the flowered news

With skull designs upon my shoes

The Friday before he passed away, Iman, his wife, tweeted, “The struggle is real, but so is God.” But that isn’t really why believers should care about David Bowie. Not ultimately. His intrigue resides not in some imagined last-minute conversion—however cryptic. It lies in the Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter posts of brokenhearted people who felt like when they were weak, or aliens and strangers in the world, Bowie helped them feel strong.

He was free. He could change on a dime. That’s the greatest fantasy—to start over. To be born again.

Gregory Alan Thornbury, Ph.D. is the president of The King’s College in New York City.