I’m a bit surprised by how much I love the British TV series Doctor Who. After all, I’m more “period dramas” than “aliens and space stations.”

But a few years ago, when I was quarantined with a houseful of sick children sleeping the days away, I decided to watch an episode or two to see what all the fuss was about. (I’m unapologetically an Anglophile when it comes to my television habits, so I’d begun to wonder if it was perhaps my duty to the Queen as a member of the Commonwealth.)

Then I fell into the time vortex.

I’ve since become that geek: the one with the TARDIS mug and the Fourth Doctor’s scarf, the one who writes a beginner’s guide to the series for newbies and can spiderweb the connections and storylines like a conspiracy theorist. If I ever get a dog, I’m determined to name her after the character Amy Pond so that I can repeat one of the show’s popular catchphrases, “Come along, Pond,” every day of my life.

Everyone has some piece of pop culture they love without moderation or reason—I’m looking at you, Jen Hatmaker with the Gilmore Girls—and Doctor Who is mine. Besides, as the Doctor himself says, anybody remotely interesting is mad in some way or another.

Doctor Who originally premiered on the BBC in 1963. The “Classic Who” era ran from then until 1989, and then the Rebooted Series (sometimes called the “New Who”) launched in 2005 and continues to dominate ratings on both sides of the Pond.

The show follows the Doctor, an ancient Time Lord with the power to regenerate into a new body whenever he is mortally wounded. Practically, that means that we have had 13 different actors portray the Doctor, each one bringing a new take on “the mad man with a box.” Its newest season debuted last month.

Despite our sci-fi stereotypes, Doctor Who showcases the emotional and spiritual heart of the genre. As Doctor and his human companions pursue adventures in time and space, we encounter themes of wonder and goodness, of suffering and our choices, of friendship and love, of war and hate, of belief and curiosity. Doctor Who is about navigating complex morality in a shifting and wild universe.

The concept of the show involves Christian symbolism; the series reboot gets referred to as a “resurrection” and each new Doctor an “incarnation.” As the central character, he’s a mysterious and powerful hero who travels through space to earth (and across the universe) to help and save. Steven Moffat, the Doctor Who writer who became the series’ show-runner in 2010 (he’s also responsible for BBC’s Sherlock), once said:

When they made this particular hero, they didn’t give him a gun, they gave him a screwdriver to fix things. They didn’t give him a tank or a warship or an x-wing fighter, they gave him a call box from which you can call for help. And the didn’t give him a superpower or pointy ears or a heat ray, they gave him an extra heart. They gave him two hearts. And that’s an extraordinary thing; there will never come a time when we don’t need a hero like the Doctor.

Whole websites are dedicated to parsing “Whovian ideas” as they relate to spirituality. The King’s College president Gregory Thornbury released a book this year about Christianity and Doctor Who. Theologian fans use the Doctor’s stories to contextualize the gospel with small group studies on how the sonic screwdriver is mightier than the sword or how we are both inside and outside of time. A collection of academic essays titled Time and Relative Dimensions in Faith: Religion and Doctor Who takes the show’s spiritual dimension seriously and aims to learn from it.

Personally, I’ve never found a better phrase to describe time from God’s perspective than the Doctor Who quote: “People assume that time is a strict progression of cause to effect, but actually from a non-linear non-subjective viewpoint, it’s more like a big ball of wibbly-wobbly timey-wimey stuff.”

In a memorable episode from season 7, the Doctor’s companions, Amy Pond and Rory Williams, are trapped flickering between two realities. They must figure out which is a dream and which is real. The dilemma exemplifies the tradeoff of traveling through time and space with the Doctor: There is never adventure without danger, never gain without loss, never love without heartbreak.

Amy is left devastated by the experience and begs the Doctor to undo it, since he’s previously stated that “time can be rewritten.” He refuses, admitting that he cannot change it for her. Even this pain is part of a larger narrative of fixed points in time upon which history rests. Amy responds bitterly, “Then what is the point of you?” And so she echoes the cry from so many of us when we suffer loss or pain or heartbreak: Please fix it, fix it now, or what is the point of you?

We don’t even know the Doctor’s real name, only the nickname of the Doctor, chosen because he sees it as a promise: “Never cruel or cowardly, never give up, and never give in.” In his best moments, he truly wants to make people better—in all the ways we understand that word. But when a man outlives everyone who has ever loved him, that is a man who has suffered. And suffering, as we know, deeply changes how we move through the world.

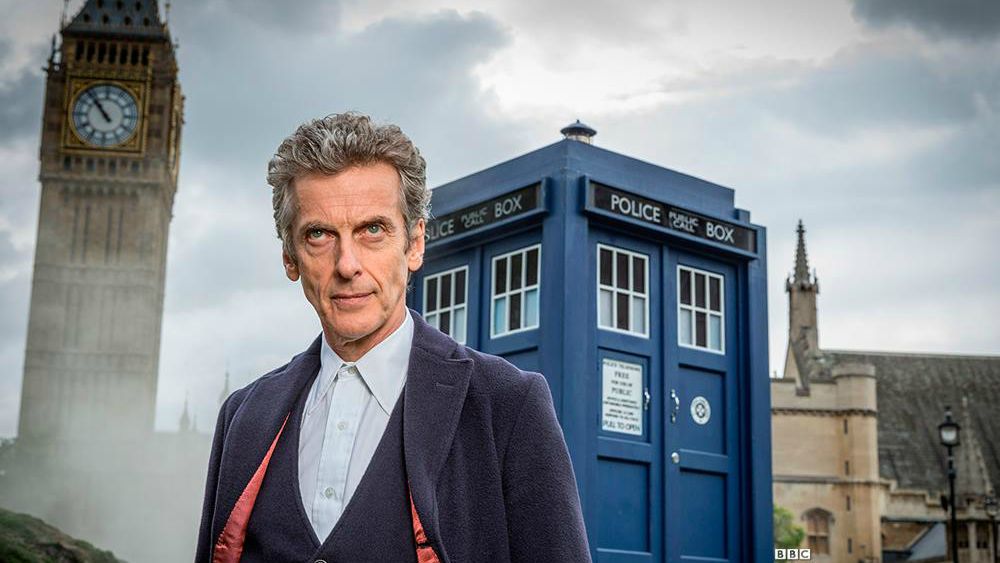

Over the past several incarnations, we’ve seen the Doctor take on many personas and personalities: a refugee from a war, a lonely angel, an eccentric undercut by grief. The Twelfth Doctor, portrayed by Peter Capaldi, embodies that weariness and wonder, once even asking his companion, Clara, if he is a good man. And Clara cannot answer that question for him. As executive producer, Moffat has taken the Doctor from lonely god to haunted hero.

Over-thinking theological geeks like me revel in all the details of the show. We enjoy sorting out how each episode fits into the Doctor’s larger narrative arc, debating favorite companions, and parsing the meaning of various moments.

Doctor Who is a sometimes irreverent TV romp through time and space, absolutely. It’s weird and hilarious and brilliant. But it also exposes the deeper longings of the human heart, how we grapple with belief and faith, our suffering and grief, our joy and curiosity, the vastness of the universe, and how we are shaped both by our choices and experiences, and more deeply, by how we love and are loved in return.

As the Doctor says, we’re all stories in the end. Let’s make it a good one, eh?

Sarah Bessey is the author of the forthcoming book Out of Sorts: Making Peace with an Evolving Faith and the bestselling book Jesus Feminist. She is an award-winning blogger and writer. She lives in Abbotsford, British Columbia, with her husband and their four tinies. You can find her online at www.sarahbessey.com or on Twitter @sarahbessey for Saturday night tweeting about the Doctor’s latest adventure.