A leading evangelical scholar says Matthew thought Peter was as bad as Judas.

Robert Gundry, scholar-in-residence and professor emeritus of New Testament and Greek at Westmont College, argues in his most recent book, Peter – False Disciple and Apostate according to Saint Matthew (Eerdmans), that “Matthew portrays Peter as a false disciple of Jesus, a disciple who went so far as to apostatize.” He believes Matthew does so to warn Christians “against the loss of salvation through falsity-exposing apostasy” and against the “ongoing presence of false disciples in the church.”

“The good news about Christ needed to be tailored to Matthew’s, Mark’s, Luke’s, and John’s [respective] audiences,” Gundry told CT. “Hence the differences between the four Gospels. We have the good news according to Matthew, and so on. We have different versions of the good news suited to different needs and circumstances.”

In the case of Matthew’s portrayal of Peter, Gundry believes Matthew revised, added to, and subtracted from Mark’s narrative in order to present Peter unfavorably. Matthew’s audience, he says, faced a more significant threat of persecution and needed warning against apostasy.

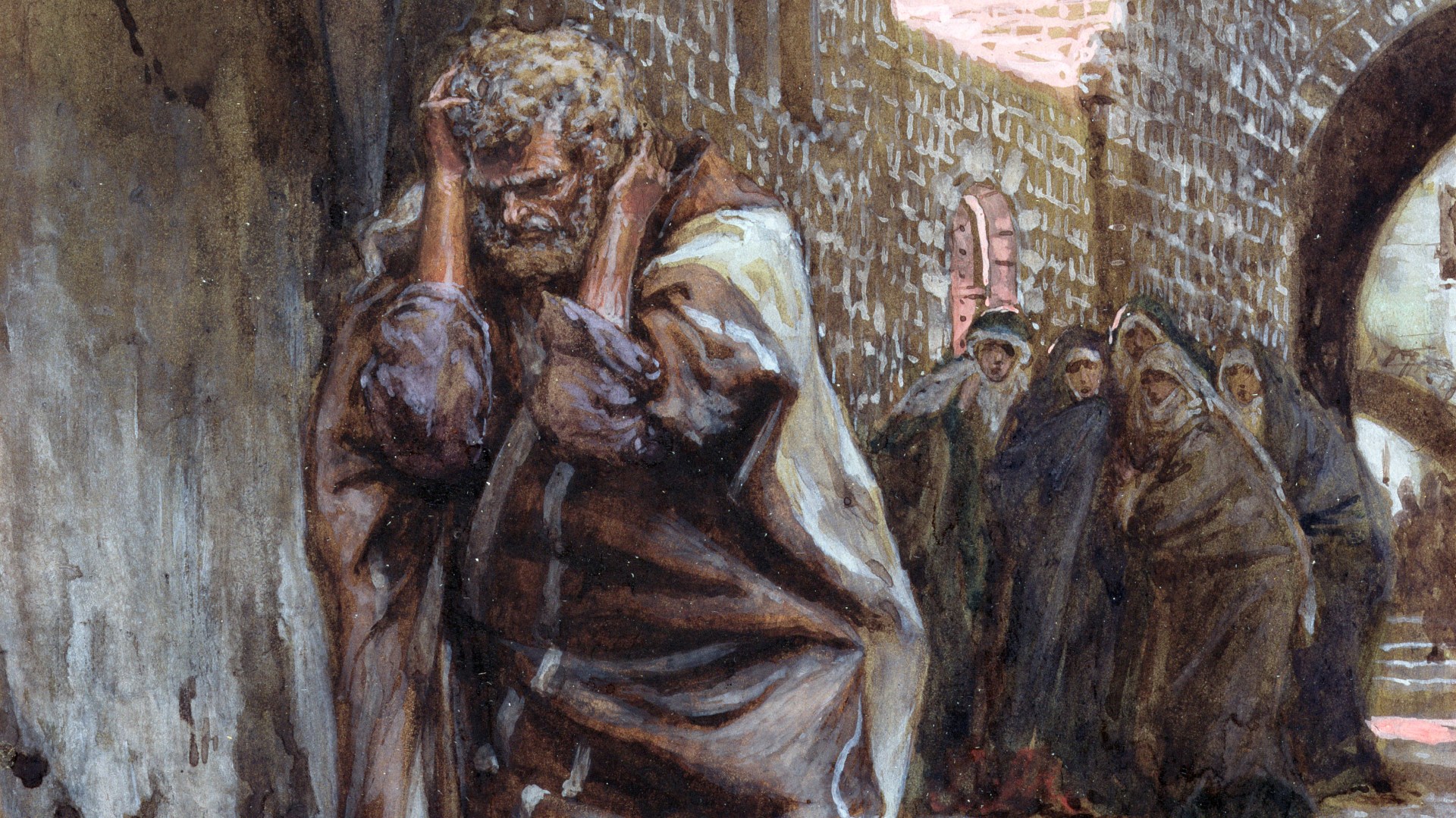

Unlike the other Gospels, Matthew does not include an account of Peter’s restoration. After denying Jesus, Peter simply “went outside and wept bitterly” (Matt. 26:75). And his weeping looks more like despair than repentance, said Gundry. Thus, Peter fits Matthew’s criteria of false disciples and apostates, and shares the same status of that of Judas.

Gundry believes that Matthew’s omission of Peter’s rehabilitation warns readers that even the most committed disciples can fall away, whereas Luke’s and John’s accounts stress that even cowardly deniers can be restored.

Gundry does not believe that conflicting portraits force readers to accept one instead of another. “No,” he writes in the book, “a choice of one portrayal over the other undermines the canonical authority of all Scripture; and systematization in the form of harmonization damages one or another, or both, of the portrayals and in the process makes one or both of them mean less than they naturally and even obviously mean.”

In a response to a lecture Gundry gave that preceded the book, Westmont provost Mark Sargent praised Gundry’s “close textual analysis” and said his argument “succeeds best in demonstrating that Matthew amplifies the false discipleship theme in his own self-contained narrative.” But he was unconvinced that “Peter’s denial of Christ in Matthew brands him once and for all as a false disciple destined for eternal damnation.” Sargent believes placing Peter alongside Judas is an interpretive misstep. Judas’s lapse “is forecast right from the get-go,” he said. “But why not Peter also if Matthew is intent on the parallel?”

Gundry believes that Matthew identifies Judas as the betrayer of Jesus from the very start because “Matthew is simply copying Mark at that point.” But Matthew “has no precedent for describing Peter in such a way as to imply false discipleship. Literarily speaking, [Matthew] creates a certain amount of suspense for the reader to see the progressive denigration of Peter.”

Sargent also said Peter’s inclusion among the 11 disciples at the Great Commission (Matt. 28) makes no sense if he was eternally outside of God’s grace. But Gundry says this doesn’t suggest Peter was restored in Matthew’s account. Rather, it reinforces Matthew’s warning against false disciples, he said. He notes that the parables of the tares among the wheat and the inedible fish among the edible fish in chapter 13 exist only in Matthew. “The whole point of those parables is that false disciples continue in the church right up to the eschaton,” he said.

But Peter’s denial shouldn’t necessarily be singled out from the other disciples’ actions, said Michael Bird, lecturer in theology at Ridley College in Melbourne, Australia. “The fact that all of the disciples fled from Jesus in Gethsemane suggests that they all were ashamed of him and in some sense proved ‘false’ by abandoning him,” he said. “Peter’s failure is indeed exacerbated, but essentially representative of the failure of the wider circle.”

Gundry is hesitant, however, to equate the disciples’ flight with Peter’s denial. “In Matthew there is a strong emphasis on the need for disciples to flee persecution,” he said. “Jesus said, ‘When you are persecuted in one place, flee to another’ (Matt. 10:23). And he himself is said to have moved from one place to another in order to escape danger.”

The novelty of Gundry’s novelty is troubling, said David Farnell of The Master’s Seminary. “Never in the history of the church has Peter ever been regarded in the sense in which Gundry says Matthew ‘portrays’ him,” he wrote in response to Gundry’s lecture. “A close look at the other Gospel writers as well as other books of the New Testament reveal quite a different picture of Peter.”

However, Gundry says he is not interested in subverting traditional views about Peter. Nor is he concerned with constructing the identity and life of Peter. Rather, he is interested in what he believes is Matthew’s distinctive account of the apostle, and the implications it might have for theology and pastoral care.

Craig Keener of Asbury Theological Seminary isn’t so sure that Matthews’s account of Peter is so distinctive. “If Matthew was meant to be interpreted in a different way than the rest of the [New Testament], he would have had to be much more explicit,” he said. Matthew’s audience presumably knew Mark’s Gospel and other stories about Peter, who was mentioned in Paul’s letters, he said.

Similarly, Bird said readers in the early church would not have treated Matthew as a free-standing narrative. “Matthew may have fully intended his Gospel to be read amidst a wider body of tradition where knowledge of Peter’s restoration and subsequent ministry was fully known.” And that, he noted, is what modern readers have as well.