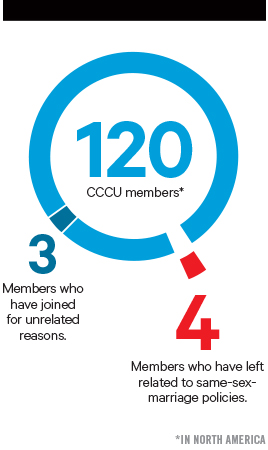

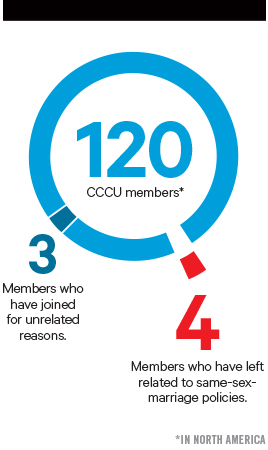

The Council for Christian Colleges and Universities (CCCU) escaped a predicament in September, when two Mennonite members voluntarily withdrew from the association.

The schools—Eastern Mennonite University (EMU) in Virginia and Goshen College in Indiana—had decided earlier this year to permit faculty and staff to be in same-sex marriages.

Before the withdrawals, two other schools—the Southern Baptist–affiliated Union University and Oklahoma Wesleyan University (OKWU)—quit the CCCU in protest.

“We believe in missional clarity and view the defense of the biblical definition of marriage as an issue of critical importance,” said OKWU president Everett Piper. “The CCCU’s reluctance to make a swift decision sends a message of confusion rather than conviction.”

The CCCU interviewed more than 120 member presidents, and found that about three-quarters of them favored demoting EMU and Goshen to “affiliate” status. That would mean they could not vote on association matters. But the Mennonite schools withdrew prior to a decision.

“Both schools have been clear from the outset that they did not want to be the cause of significant division within the membership,” stated the CCCU board.

The departure leaves the CCCU united about same-sex marriage but with deeper questions: How are Christian colleges engaging a post-Christian culture? And what part, if any, does denominational theology play in whether schools choose to engage or withdraw?

Both evangelical and Anabaptist traditions value separation from the world. But they express it in different ways, said historian Jared Burkholder at Anabaptist-affiliated Grace College, a CCCU member.

While progressive Mennonites see inclusion, hospitality, and compassion as ways to separate from a brutal and oppressive world, conservative evangelicals assume Mennonites and other Anabaptists are giving in to worldly pressure to tolerate sin, he said. So it’s not surprising that the schools to include noncelibate gay employees were Mennonite, and the schools to object were Baptist, a denomination where autonomy is important, and Wesleyan, a tradition that values holiness.

“In a very general way, I think the denominational differences help to shape these matters,” said Trinity Evangelical Divinity School president (and former Union president) David Dockery. But such influence is waning, he said.

The challenge for schools of being “in the world but not of it” is as old as modern education. Many Christian colleges were founded to separate themselves from the values of secular culture, said sociology professor John Hawthorne at Spring Arbor University, a CCCU member.

“In this context, for Union and OKWU, being a Christian university means you have to have a strong stance in separation from the broad cultural trends,” Hawthorne said. “This is how people know you’re a Christian school.”

The largest crisis of Christian higher education was from the 1920s to the 1960s, when many of the country’s most elite Christian schools (such as Duke, Northwestern, and Syracuse) downplayed their faith-based identity. That left a remnant of Christian schools to band together and begin the precursor to today’s CCCU, said William Ringenberg, historian at Taylor University and author of the forthcoming book The Christian College and the Meaning of Academic Freedom.

“We don’t want to repeat the old fundamental withdrawal,” said Rod Sider, theology professor at CCCU member Eastern University’s Palmer Theological Seminary. “At the same time, we need to be faithful to what we believe is the biblical teaching.”

In this case, most CCCU presidents agreed that the actions taken by EMU and Goshen “placed them outside the bounds of the CCCU’s membership,” according to the council. However, most presidents also were willing to partner with the two schools; less than 25 percent wanted to sever ties completely.

In their interviews, the presidents emphasized the importance of working together in the face of challenges to religious liberty, said CCCU president Shirley Hoogstra in a telephone press conference. “If there was a way for the CCCU to remain strong and advocate for the kinds of liberties we need [in order] to fulfill our mission, that was a primary goal for our presidents.”