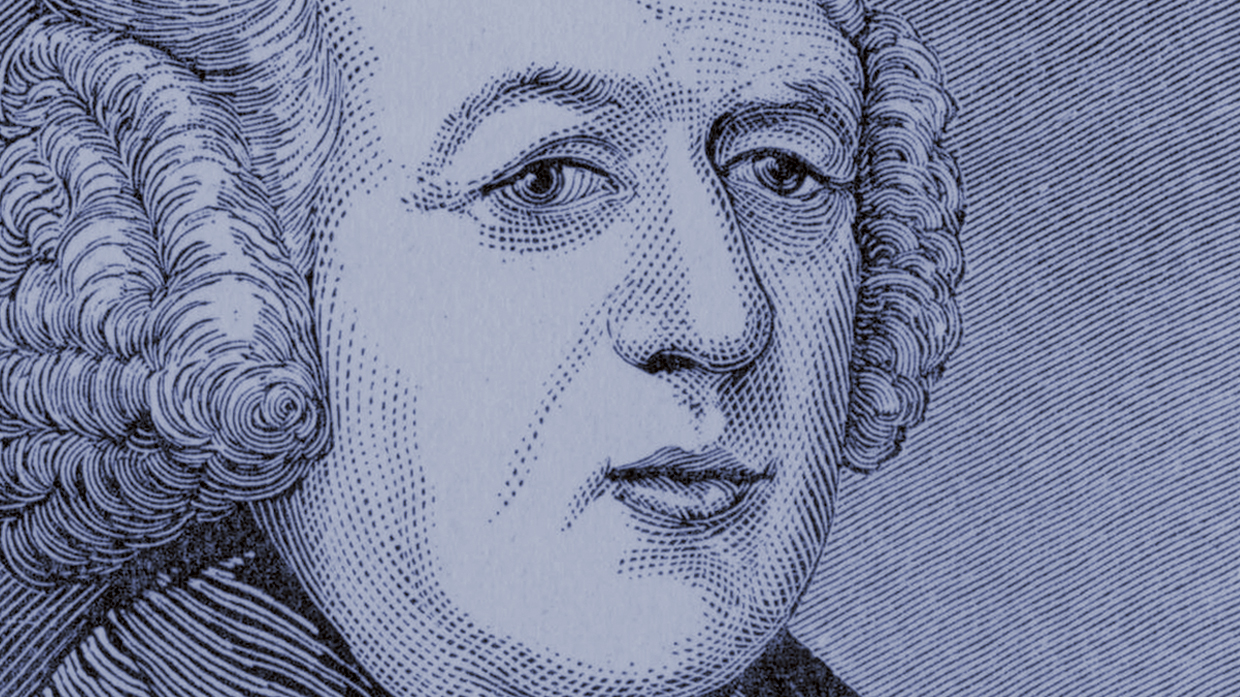

Author Tony Reinke spoke with us about his latest book Newton on the Christian Life: To Live is Christ. While many might know some of the major moments of Newton’s life, Reinke shared with us about the pastoral life of John Newton and the vital lessons pastors today can apply from John Newton.

Mention John Newton and many will think “Amazing Grace" or "slave-trader," but you’ve made the case in this book that there was a whole lot more to Newton. Was that your objective with the book?

Newton’s life was dramatically worthy of an HBO miniseries like John Adams. Newton lived through massive shifts in historical and geopolitical power (including the American Revolution, but on the losing side). As a young man, his life was full of personal drama, heated rebellion, a lifelong romance, some naval fighting, and decades of seafaring. Eventually he sailed slave ships across the Atlantic, nearly died at sea in a storm, was saved from his sin, and converted to the Christ he hated for 20 years. If you fast-forward to the end of his life, he worked as an abolitionist along with his young friend William Wilberforce. Newton was on his deathbed when he learned that Britain abolished its Atlantic slave trade.

So that’s the cinematic arc of Newton’s life that could be brought to life on screen (William Shatner being the physical doppelgänger). But visual drama is never the full story. In between all these theatrics, Newton pastored for over 42 years—and the pastoral life is, well, pastoral, and far less dramatic. But those quieter decades of John Newton’s ministry are deeply compelling: years of preaching sermons, writing hymns like “Amazing Grace,” and sitting in his home writing hundreds of pastoral letters to inquirers and friends and family tell an unforgettable story.

In Newton on the Christian Life, I focused on Newton’s letters, which show a remarkably dramatic story of the internal turmoil and conflict that rage within the Christian life. You can’t shoot this dramatic battle on screen, but it’s no less a war of the Christian’s affections and loves. As Christians, we struggle to find our source and satisfaction in God, we struggle against all the false bait of the world, we struggle against our flesh, and we struggle against the devil. Newton saw the heart as something of a Middle Earth, an expansive terrain with forces in constant tension and frequent combat. As a pastor with a long backstory of personal sin, Newton was never naïve to this inner warfare, and he was on the frontlines helping others in the battle.

What was Newton like as a pastor?

He was approachable, he made friends easily, and he was a celebrity. At the age of 39, just a few months into his first pastorate, he published his autobiography, and it became an international bestselling book that spread all over the English-speaking world.

Newton was spiritually attractive to the entire scope of ages (from little children to the old) because he was a gentle realist—a trusted grandfather able to deliver clear wisdom to real people. He never forgot his own backstory of wickedness. Knowing his own life story helped him avoid being a pastor preoccupied with theological speculation. Newton was a man of utility. This practical realism made him an incredible friend to Christians who were struggling in the Christian life, and the people drawn to him struggled with everything from depression, sorrow, suicidal thoughts, alcoholism, and unresolved doubts and insecurities about their own spiritual health.

Newton saw the heart as a Middle Earth, an expansive terrain with forces in constant tension and frequent combat. As a pastor with a long backstory of personal sin, Newton was never naïve to this inner warfare, and he was on the frontlines helping others in the battle.

Newton had a profound influence on William Wilberforce. What did Newton see in this young abolitionist?

When they first met, Newton was in his early 40s. William Wilberforce was 8. Separated by many years, they connected well and Newton saw a lot of promise in the boy from a very early age. This relationship led to a key meeting many years later. Wilberforce was a clearly gifted leader and could have become a well-respected pastor in England, but Newton persuaded the 26-year-old to stay in politics and use his leadership gifting to influence policy, especially in the cause of abolition.

Together in London they celebrated the Act of Abolition of the Atlantic Slave Trade, which passed by a 283/16 vote in February 1807. Wilberforce was 47. Newton was 81. Less than a year later, Newton passed away.

You have a chapter on Newton and battling insecurity. Given his background, how much was this a factor in Newton’s personal life and ministry?

Life in the eighteenth century was especially insecure and full of anxieties (ours is too, but we can shield our attention from the insecurities). Many of the letters Newton received were from friends who were facing desperate losses, or facing spiritual questions about whether God really loved them genuinely.

Newton was not the rock people needed, but he knew the Rock, and he would point his friends to Christ for their security. As I show in the book, from a myriad of angles, this really is the key to Newton’s success as a pastor.

Newton stressed this over and over again: Christian leadership is first and foremost an explicit articulation of the beauty of Christ. Pastors cannot just tell people that Christ is great, they must show them he is great. Pastors must strive to articulate the substance of Christ.

What surprising lesson would you expect pastors to learn from the life of John Newton?

Two come to mind.

One, to make a clear distinction between gifts and grace. If you are a pastor, God has given you gifts. You have skills that others appreciate, and seek to emulate. Naturally, over time, the pastor will find his identity in his vocation, not in the unmerited grace of Christ. That’s just how the sinful heart works. We take for granted the gifts God has given us, we ignore his grace, and then we arrogantly feed off human praise.

Newton liked to say: Usefulness is the last idol that a pastor must part with. If he doesn’t see usefulness as an idol, if he doesn’t see his identity in the solid gold of Christ (not in the tinsel of personal spiritual gifts), that pastor will make a royal mess of his church, especially as he ages and the opportunities to pass leadership on to a new generation come and go. Be secure in Christ (who is your eternal security), not in your church position (which is your temporary occupation).

Second, to see that in the course of ministry, we assume Christ very often. Sermons will be preached, counseling sessions will be led, musical worship will be enjoyed, and Christ’s person will be absent from all of it. And usually unnoticed by everyone! So ask yourself: What would a Muslim have learned about Christ from our last service?

The chief fault of Christian leaders is taking Christ for granted. Christ is assumed. His word is assumed. That Christ now reigns over creation in heaven will be assumed. His death and resurrection will often get assumed. So Newton stressed this over and over again: Christian leadership is first and foremost an explicit articulation of the beauty of Christ. Pastors cannot just tell people that Christ is great, they must show them he is great. Pastors must strive to articulate the substance of Christ.

How cool was it to see the President singing Amazing Grace at the funeral of slain Charleston pastor Clementa Pinckney?

That beautiful moment was 300 years in the making! Here’s the backstory. 265 years ago, John Newton the non-Christian slave trader sailed into the port of Charleston and unloaded 150 African slaves off a ship (October 1747). 242 years ago, John Newton the Christian pastor wrote the hymn “Amazing Grace” for his church in England (December 1772). 227 years ago, John Newton formally joined Wilberforce in the abolitionist movement (January 1788). Recently, our president led a historic church in an impromptu singing of Newton’s hymn, “Amazing Grace” in Charleston (June 2015).

The amazing grace behind this moment in our recent history is simply astonishing. It gives me chills just writing about it.

Daniel Darling is vice-president of communications for the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission. He is the author of several books, including his latest, Activist Faith.