How do I live as a woman in this wild corner of the world? I couldn’t answer that when I first came to the Alaskan wilderness as a 20-year-old bride of a fisherman. I couldn’t even ask the question, mostly because I did not consider myself a woman. Nor did I think of myself as a girl.

I didn’t think about gender much, partly because I grew up in a genderless household, and partly because of the culture itself. In the ‘70s, men and women alike wore bell-bottoms, parted their long hair in the middle, and clogged about on platform shoes.

Science and media pundits told us that gender differences were purely social constructs—we were all products of our environment. Progressive parents gave their young daughters trucks underneath the Christmas tree, and boys received dolls. Even middle-aged and elderly couples walked hand-in-hand down the sidewalk in matching outfits.

My husband and I bought it all. In our dreamy stage, we decided we would work together in commercial fishing, and then we’d go ashore and cook dinner and wash dishes together. I quickly woke up from that dream.

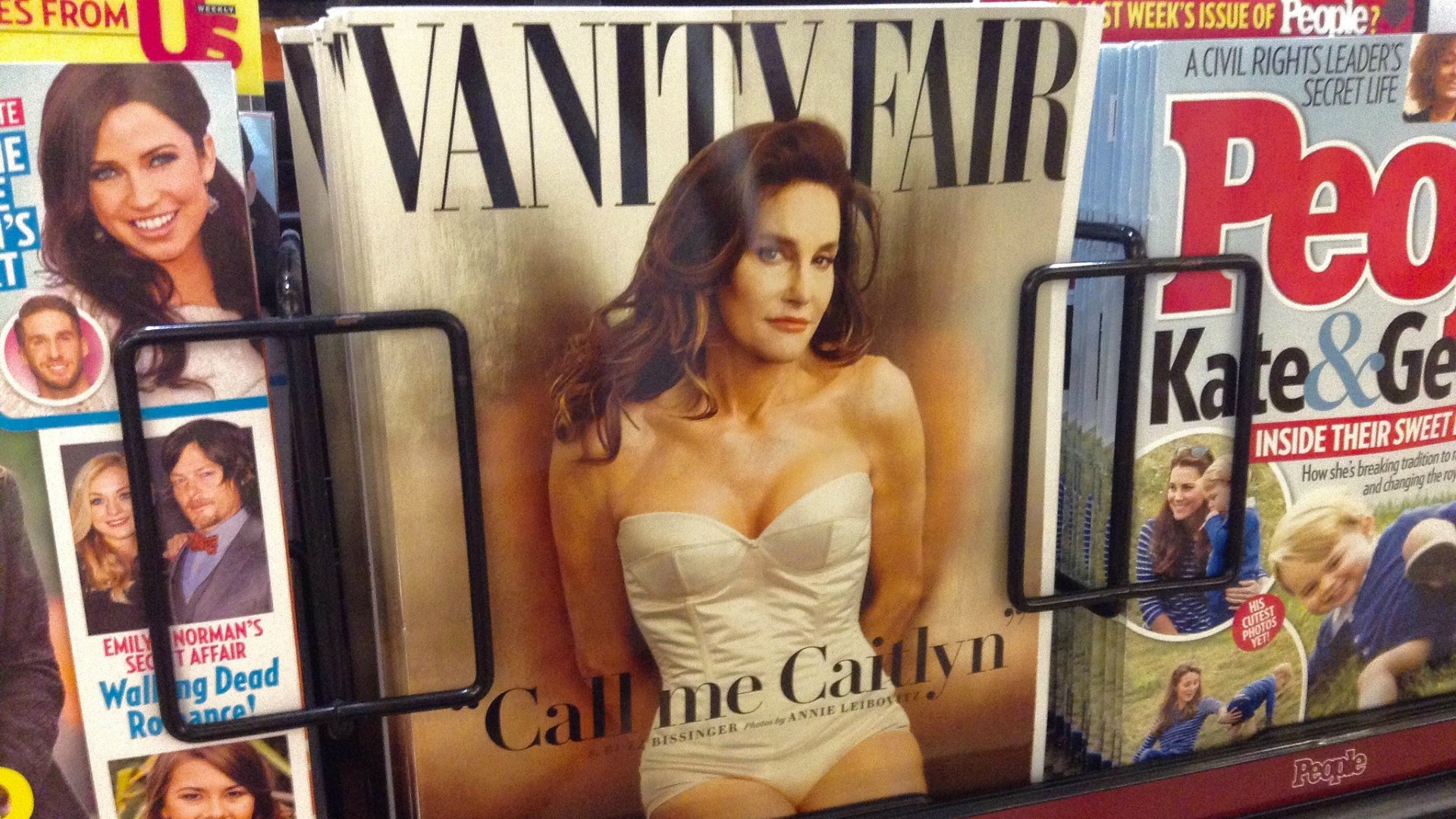

And as a society, we’ve moved far from the ‘70s conception of gender. Last month, the split image of Bruce-turned-Caitlyn Jenner displayed his former exaggerated version of masculinity, through athletic prowess, and current hyper-femininity, obtained through surgery, hormones, heavy makeup, and a Vanity Fair photo shoot.

Advances in science, and particularly neuroscience, have delivered round after round of breakthroughs, concluding that—gird your loins—men and women were indeed different. In physiology, brain function, communication style, hormone pattern—starting in utero.

Nearly every branch of science has cataloged the astonishing ways that men and women are distinct from one another. They’re so far apart; in fact, one of the most popular books of the ‘90s placed men on Mars and women on Venus. In less than two decades men and women moved from walking hand-in-hand in matchy matchy outfits to inhabiting different planets.

The neuroscience has been helpful, as far as it goes. We can sigh in relief when we discover that those things about our spouse (or sibling or parent) aren’t their own aberrations, but fairly normal behavior for their gender. I own a popular Christian marriage series that has readers laughing at the male species, who can’t multi-task to save his life, who speak 17 words a day (actually studies say 7,000), who have no clue as to their actual emotional state, etc. Then we hit the female version: women who speed-talk nonstop, jump between topics, fixate on minute details, and on and on.

These are now assumed commonplaces, particularly in the Christian community: men are rational; women are emotional. Men are lone wolves; women are cooperative. Men are single-track; women multi-task. Everyone reading this can list a dozen more.

Predictably, we swung from one pole to the other, from nurture to nature, now endorsing gender stereotypes with the officiousness and blessing of science. The genders have been so parsed and catalogued, I believe, we’re feeding the current crisis in gender identity and expression.

I’m not minimizing the difficult reality of Jenner’s condition, gender dysphoria, and others like Jenner. Still, we’re all experiencing the consequences of a cultural fixation on gender. A man or woman, a boy or girl, who tends toward the features considered “the other” might question his or her identity in a way that may not have happened a few decades ago.

Men, it seems, get hit particularly hard. Women and girls enjoy a generous allowance that recognizes the athlete, the supermodel, the CEO, and the mother as equally valid expressions of femaleness. Many parents, like me, encourage our daughters to be pitchers and point guards (and fishermen) rather than princesses. But cultural expectations of masculinity are far stingier. If a man is gentle, compassionate, artsy, empathetic, cultivates beauty in his life, talks with his hands, enjoys the friendship of women, his masculinity and sexuality is instantly questioned.

Nor are the stereotypes themselves gender equitable. After suffering generations of sexism, women fare better than men in some settings. Society lauds women for their neural plasticity; they’re flexible, cooperative, compassionate, honest. Women outpace men in higher education, in employability, and in a score of other measures. And at the movies, they’re as glamorous and sexy as ever… but also as kickass as the men.

And our male counterparts? They’re still athletes and superheroes, but not much else. We’ve watched lame, pathetic fathers in sitcoms for more than 20 years. The moral failures of male politicians have come to feel like the norm. Men undergo critique for their single-lobed rigidity, leading one social observer, Hanna Rosin, to her 2010 cover story for The Atlantic, “The End of Men.” In my day, many girls wanted to be boys, myself included, because the boys held all the power. No longer. Now it is men who want to be women: three times as many men as women are undergoing sex reassignment surgery.

I’m not explaining away Jenner’s transformation on the media-driven ascent of women in our time, though it may be a contributing factor. That double image of Bruce and then Caitlyn is a fitting poster for the growing gap between the genders. But even more than this, Jenner’s interview and Vanity Fair coverage poignantly highlights that our sexualized obsession with gender is failing us.

We seem to recognize that we have a problem, but can’t settle on a way to resolve it. One response has been to identify the issue as an obsession with “binary categories,” and to fix it with more categories. Facebook provides more than 50 choices for gender identification, as do many LGBT groups. But drawing more lines and sorting people into ever-smaller boxes only augments the larger problem.

Our identity and self is neither fully contained nor fully explained by our manness or womanness or any shade or stripe in between. Indeed, we’ve spent so much time dividing and defining our sexual identity, even in the church, we have lost our most essential identity and with it, our sense of unity.

Yes, God made woman and man different, but that’s not the end of the creation story. Man was made by God, Woman was made from Man, and Man is born from Woman. From the very beginning, we are part of each other. We long for each other. We mirror each other. We reflect the image of God to one another. (But we can misinterpret these longings. Might it be possible, at times, that our God-created longing for union and connection with the other gets mistaken for the desire to “be” the other?) And the New Testament overflows with all that we share in the kingdom of God: we are joint-heirs, co-laborers, fellow citizens, children of God, all indwelt by the same Holy Spirit of God.

Our identity and self is neither fully contained nor fully explained by our manness or womanness or any shade or stripe in between.

Our central concern is not whether we measure up to the current cultural notions of femininity or masculinity or anything in between, but to the person of Christ. Christ was indeed a man. Yet, his primary identity was not his manliness, but his relationship with God.

Scripture calls men and women alike to be conformed not to the pattern of the world but to the pattern of Christ himself (Rom. 12:12). God commands us to live as he did: to love God with all our being, to “renew our minds,” to “be united in love,” to “be in full accord and of one mind,” to “love our neighbor as ourselves.”

Our aim is not manliness or womanliness but godliness, which includes compassion, kindness, mercy, strength, perseverance, courage, submission, and many other virtues, traits too long parsed out to one gender or the other. In almost 40 years of marriage, when my husband and I struggle, it is not our designation as woman or man or even husband or wife that divides, but rather sin and selfishness. And, after all these years, we finally do work together in fishing and then share in the dishes.

I’m not attempting to usher us all back to the extremes—and bad fashion—of the unisex ‘70s. We need not pretend we are all alike, or that gender doesn’t matter, but gender has mattered far too much. A settled identity as a man or woman or homosexual or transwoman or genderqueer or any of the other LGBT designations will not answer our deepest human longings—to know and be known, to love and be loved by the one in whose image we’re made. Nor do all the delineations for gender provide a way forward for living in our shared humanness and createdness.

Being inhabited by the Spirit and moving toward God-like-ness can heal the dissonance we feel within ourselves, and also the differences and divisions among us. This is my hope, that whoever we are, we will be known not for our gender category but for our mercy, our wisdom, our kindness, our humility, our grace, and our love. If we allow the Holy Spirit to do this in us, we will be exactly who we were created to be, inside and out.

Leslie Leyland Fields is a CT contributing editor and the author of nine books, most recently Forgiving Our Fathers and Mothers: Finding Freedom from Hurt and Hate (Thomas Nelson). She lives in Alaska, where she works in commercial salmon fishing with her family.