In 1973, after more than a dozen years of turning down invitations to preach in racially segregated South Africa, Billy Graham finally held the first large-scale, mixed-race public event in the nation’s history. “Jesus was not a white man,” he declared to the 45,000 gathered in Durban. “He came from that part of the world that touches Africa, and Asia, and Europe, and he probably had brown skin.”

A lot of people still have trouble imagining a brown Jesus. In December 2013, Fox News anchor Megyn Kelly riled media pundits by insisting that Jesus was white. The 2014 movie Son of God featured a decidedly white actor in the role of Jesus. In Exodus: Gods and Kings, director Ridley Scott used white actors to play key Egyptians and Hebrews; he claimed he couldn’t have financed the film had the principal characters looked too Middle Eastern.

The kerfuffle over Exodus got me thinking about the biblical paintings by Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859–1937). Tanner was the first African American painter to receive international acclaim and a pioneer in using Middle Eastern models for biblical figures. Tanner came from an illustrious family. His father was a leading bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal Church and editor of the church’s paper, the most widely circulated African American publication at the time. Henry’s sister was the first woman (black or white) to practice medicine in Alabama, and Henry studied at both the prestigious Philadelphia Academy of Art and the Académie Julian in Paris. Many of his paintings were exhibited at the Paris Salon.

Tanner wanted to put us, the viewers, in the frame, for those stories are addressed to us and are about us.

Though Tanner sometimes painted a dark (though not African) Jesus—and though he settled in France to escape American racism—he was not on a race mission. His mission was to universalize the biblical message: “My efforts have been to not only put the biblical incident in the original setting . . . but at the same time give the human touch ‘which makes the whole world kin’ and which ever remains the same.” Believing that Bible stories illuminate the universal human experience and offer an encounter with the living God, Tanner wanted to put us, the viewers, in the frame, for those stories are addressed to us and are about us.

The Annunciation, perhaps his most reproduced painting, does this remarkably well. His is not the standard double profile of an enormous angel with parrot wings confronting a pious Mary sitting in the garden of an Italian villa (think Fra Angelico). Instead, Tanner’s angel is a featureless, brilliant burst of light. Mary, on the other hand, sits in an unadorned bedroom in the middle of the night. The viewer’s eye is thus directed to the wonderstruck young woman. Because Mary is turned toward us, we share her reaction, listening with her for the divine Word as she receives the angel’s message and the Spirit’s overshadowing.

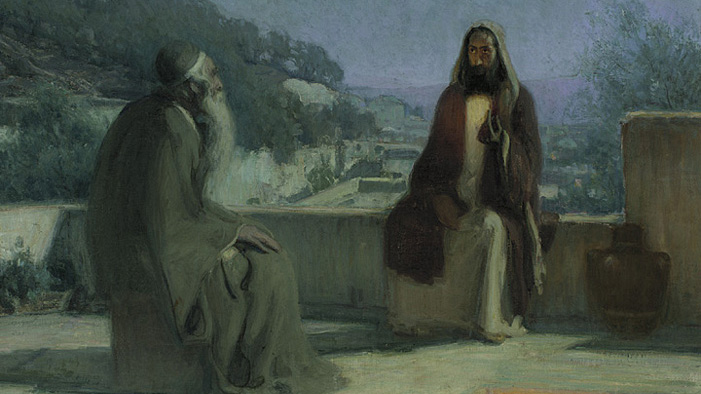

Tanner’s first painting of Jesus and Nicodemus is a similar contrast to standard practice. When James Tissot, the most popular illustrator of biblical scenes in the 1890s, painted The Interview between Jesus and Nicodemus, he gave us a profile of the two seated men, heads bent together intimately. But Tanner’s dark-faced Jesus faces us squarely. Tanner makes us, alongside Nicodemus, spiritual seekers.

In The Resurrection of Lazarus, Tanner again departs from the standard portrayal. When Jesus commands “Lazarus, come forth!” both Rembrandt and Tissot isolate him visually from the mourners. Tanner’s Christ, by contrast, stands with the mourners (among them a turbaned man of distinctly African appearance), not pointing upward but reaching out toward the awakening Lazarus, spreading his palms in a gesture of welcome. By standing with the mourners—we are all mourners—Tanner’s Jesus includes us in the story.

Similarly, The Two Disciples at the Tomb has none of the usual props—no angel, no folded grave clothes. Tanner shows us instead the faces of Peter and John, illuminated by a light from the tomb. Reflecting both their grief and their budding resurrection faith, their faces could be ours.

The son of a preacher man, Tanner used images, not words, to extend an invitation. “I will preach with my brush,” he said. He did so by putting us in the picture, allowing us to share Mary’s wonder, Nicodemus’s searching questions, the sorrow of Lazarus’s friends, and the disciples’ newborn faith.

May we have the eyes to see Tanner’s message.

David Neff is the former editor in chief of Christianity Today.