About 10 years ago, I taught an adult Sunday school series in which I considered three ways to understand evangelicalism. Is it a movement defined primarily by its (American) history, a narrative arc leading from early 20th century fundamentalists through neo-evangelicals like Billy Graham to the more recent Religious Right? Is it a theological system, most memorably defined by David Bebbington, emphasizing the Bible, the Cross, conversion, and activism? Or is it a subculture defined primarily by its consumption of curated books, media, college degrees, VBS curricula, and other religious products?

My third hypothesis did not sit well with the Sunday school class. I had not presented the three possible definitions as mutually exclusive, but even addressing commercialism in that setting was discomfiting. No one wants to be told that what they think of as cherished convictions are actually mere consumer preferences.

In the years since that class, a swelling tide of scholarship on the business of American evangelicalism has made its economic entanglements harder and harder to ignore. Key titles include Bethany Moreton, To Serve God and Wal-Mart: The Making of Christian Free Enterprise (2009); Darren Dochuck, From Bible Belt to Sunbelt: Plain-folk Religion, Grassroots Politics, and the Rise of Evangelical Conservatism (2010); and Kevin Kruse, One Nation Under God: How Corporate America Invented Christian America (2015). Darren Grem, author of Corporate Revivals: Big Business and the Shaping of the Evangelical Right (forthcoming), is also working on an edited collection tellingly titled The Business Turn in American Religious History.

Timothy E. W. Gloege’s Guaranteed Pure: The Moody Bible Institute, Business, and the Making of Modern Evangelicalism is a strong entry in this field. Eminently readable and frequently brilliant, the book argues that evangelicalism reflects a consumer ethos because both outlooks originated in the same era and, in many cases, grew from the efforts of the same men. “Between the Civil War and World War I,” he writes, “a group of ‘corporate evangelicals’ created a new form of ‘old-time religion’ that was not only compatible with modern consumer capitalism but also uniquely dependent on it.”

A Safe, Reliable Product

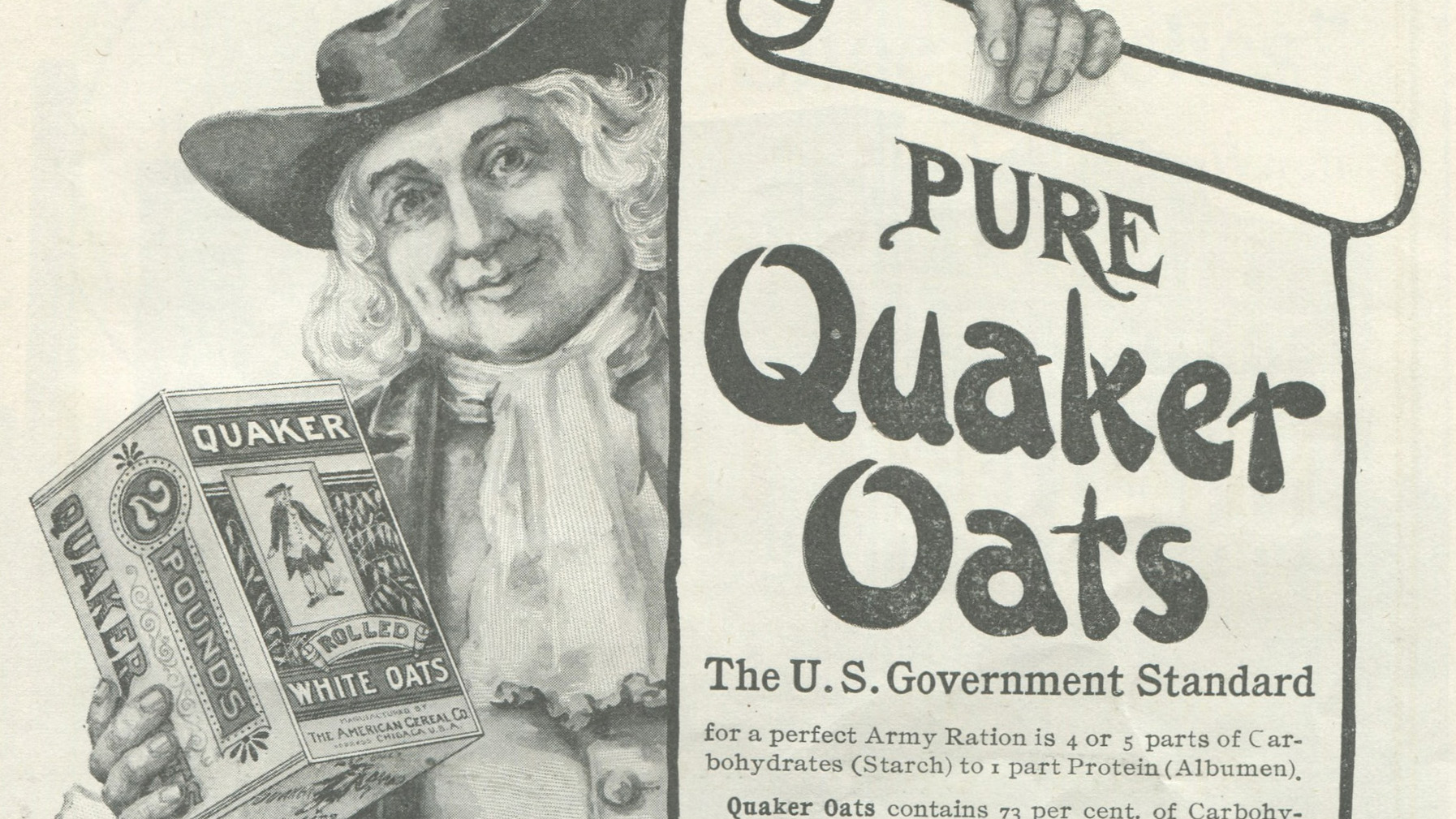

Henry P. Crowell serves as Gloege’s central example of this connection. In 1882 Crowell purchased an oatmeal mill. At the time, oatmeal was sold by the scoopful at general stores across the country. Supplying that kind of basic commodity was no way to make a fortune, so Crowell began selling his oatmeal in sealed packages adorned with the portrait of a smiling, trustworthy Quaker gentleman holding a scroll that read, “Pure.” It no longer mattered whether the shopkeeper kept the ants out of his oat barrel, or whether his suppliers shipped the product in sanitary containers. Customers could trust Quaker oatmeal because of the promise on the label. As Gloege writes, “Through the trifecta of trademark, package, and promotion, a consumer society was born.”

In 1904, Crowell was elected president of the board of trustees of a struggling Moody Bible Institute (MBI). Evangelist Dwight L. Moody had possessed a knack for attracting deep-pocketed donors to broadly Christian endeavors, but his death in 1899 left his Bible school in the hands of men inclined toward more angular interests in premillennial dispensationalism and faith healing. Crowell steered the institution back onto a respectable and financially sustainable path by following the same instincts that had served him well in the cereal business.

Quaker Oats bested its competition by appealing directly to consumers who sought a safe, reliable product. Amid increasingly heated conflicts in denominations and universities regarding the inspiration of Scripture, the reality of miracles, the origin of species, and the means of salvation, millions of American churchgoers sought a safe, reliable theology as well. Thus, in Gloege’s accounting, the religious marketplace as we know it was born:

Respectable ministers and other religious workers were the religious “retailers,” while the laity was the end “consumer.” Already, Crowell’s efforts at MBI had alerted him to the fact that there were gatekeepers impeding distribution of his religious product. Many religious “retailers” and “consumers” were simply unfamiliar with his product and thus understandably suspicious. In addition, most local churches had “wholesale” relationships to their respective denominations, which were their theological suppliers. Whether a denomination was compromised by liberalism or stubbornly committed to their stale churchly product sold under their private label, it was resisting the conservative evangelical alternative. In both cases, the solution was to bypass the denominations and appeal directly to the laity….By creating demand from below, denominations would be forced to make changes in their seminaries, theological journals, or even creeds. If they refused, a religious consumer might find another church home more amenable.

The categories in this passage require some explanation, because Gloege does not use them in quite the same way as other scholars. “[L]et me explicitly reject the practices of equating ‘evangelical’ with ‘conservative Protestant’ and positing ‘liberal’ as its opposite,” he writes in the introduction. Properly, “conservative” and “liberal” describe approaches to tradition, as something to be continued or substantially modified. According to Gloege, the approach to tradition was not the main point of conflict between Crowell and his competitors, in part because the self-styled conservatives were breaking with tradition, too. Three important “conservative” tenets—dispensational premillennialism, a mechanical understanding of biblical inspiration, and insistence on a literal seven-day creation—were all quite new at the turn of the 20th century, though their champions cast them as timeless truths only lately come under attack by over-educated liberals.

Instead, Gloege contrasts individualistic evangelicals and churchly Protestants. The former group identified itself, in a rhetorical coup, as “conservative.” The latter group included folks more and less sympathetic to the new conservatives’ theology but commonly uneasy about direct-to-consumer religion. Evangelicals (Gloege also uses, and explains, the related term “fundamentalist”) trusted nondenominational institutions like MBI to supply them with Christian workers, periodicals, and radio programs, just like they trusted the smiling Quaker gentleman to serve them “pure” oats. Churchly Protestants, by contrast, placed faith in denominational hierarchies and divinity schools to ensure quality, just like customers had once placed faith in the local dry goods store manager and his unseen supply chain. As we know, one mode of purveying spiritual and physical food proved more successful in the 20th century than the other.

Spiritual Dividends

Throughout the book, Gloege pays more attention to MBI’s internal struggles, and to its challenges from the premillennial and Pentecostal fringes, than to its looming collision with liberals as embodied by the cross-town rival University of Chicago. This focus tacitly supports his assertion that consumerism influenced (one might say infected) modern evangelicalism in ways it did not influence other Protestant traditions. If Gloege had attended to liberals before his book’s final chapter, though, he would have found suggestive similarities.

Moody sold “shares” to raise funds for his Chicago Sunday school, promising spiritual dividends. The Christian Century tried the same tactic a few decades later. Oilman Lyman Stewart bankrolled Biola University and publication of The Fundamentals; oilman John D. Rockefeller bankrolled the University of Chicago and publication of Harry Emerson Fosdick’s sermon “Shall the Fundamentalists Win?” Crowell applied his dictatorial management methods at both Quaker Oats and MBI; liberal theologian Shailer Mathews, in a 1912 book, advocated Scientific Management in the Churches. None of these parallel efforts was precisely equivalent, but they all reflected a desire to work with rather than against the new consumer economy.

The operative distinction between Virgin-birth-affirming and Virgin-birth-denying Protestants, then, was not whether they attempted to promote their religion using modern business principles but whether they succeeded in doing so. Here, Gloege’s astute contrast between individualistic and churchly orientations provides an explanation.

Crowell and many (though not all) of the men who worked with him at MBI were laymen. MBI did not ordain anyone or uphold any particular church polity. This training enabled graduates, as individuals, to join the large, theologically conservative population working within denominations or to avoid denominations entirely. Subscribers to Moody magazines and listeners to WMBI were similarly free, as individuals, to identify with churches or not.

Liberal Protestants, though, were intrinsically churchly and thus committed to the “wholesale” model. Ordination and polity mattered in their world, and they pursued their religious aims through conglomerations such as the Federal (later World) Council of Churches. Unfortunately for them, as one of my seminary colleagues is fond of saying, “Real people don’t care about polity.” Systems that were intended to unite the body of Christ, while also assuring quality control, instead disempowered laity and alienated potential new members. The proliferation of non- and post-denominational congregations today testifies to Gloege’s insight.

Gloege is no muckraker, following the money to the rotten core of an institution. He analyzes resonances between evangelicalism and consumer capitalism without railing against either. His portraits of Moody, Crowell, and others are lively, and his descriptions of administrative maneuverings at MBI and the Fundamentals project are both well-researched and clear. Evangelicals might not like everything they read in this book, any more than my Sunday school class liked what I suggested about their consumer choices, but they will be informed, engaged, and challenged. Guaranteed.

Elesha Coffman is assistant professor of church history at the University of Dubuque Theological Seminary and author of The Christian Century and the Rise of the Protestant Mainline (Oxford).