A Moody Bible Institute professor has called on the school to abandon the term white privilege in discussions about diversity, calling it “inflammatory,” “repugnant,” and “unworthy of Christian discourse.”

“I suggest we should rip the term ‘white privilege’ out of our discourse at Moody,” wrote theology professor Bryan Litfin in a letter to the editor published April 15 in the student newspaper. “The underlying issues that need to be addressed should be described with more wholesome, less divisive terminology.”

Litfin proposes five reasons why he believes the term is “intended to address an important topic” yet isn’t biblical enough to be effective because it is “taken straight from a radical and divisive secular agenda.” “The problem is, the term itself is inflammatory, so the real topic goes unheard because of the offense,” he wrote, concluding, “Why employ terms that divide the body of Christ? As students of God’s Word, let us draw our terminology from the Bible, not the wisdom of man.”

The letter follows an apology he made in March for comments he had made on social media about a campus diversity event.

Flyers for the event, called “White Like Me,” said it would feature “thoughts on race from the perspective of a privileged person,” according to the Chicago Tribune.

A flyer for the event, hosted by a Moody student group called Embrace, was vandalized. A photo of the damaged flyer, with the word “privilege” crossed out, was posted online.

Amid discussion of the vandalism, Litfin criticized the idea of “white privilege” and the event itself.

“Using the term ‘white’ to categorize millions of people under one catch-all term, then pegging them as elite oppressors, is offensive on its face and unworthy of Christian discourse,” he wrote on Facebook.

He later apologized, telling the Tribune that his comments were not “worthy of what a professor should do.”

Following the controversy over the defaced flyer and Litfin’s first comments, Moody President Paul Nyquist had emphasized the school’s commitment to diversity in a letter to college community.

That commitment includes talking about white privilege, he said.

“People who are white, such as myself, because we are of the majority culture, often fail to understand the privileges we enjoy due to our skin color, for it is all we have ever known,” he wrote. “Therefore, the conversation hosted on our campus last week is part of an ongoing effort to bring greater campus-wide understanding to the issue and I applaud and affirm its purpose.”

The debate at Moody is part of a larger conversation about race and ethnicity at Christian colleges, driven in large part by the country’s changing demographics.

The term white privilege was first popularized in a 1989 essay by Peggy McIntosh, associate director of the Wellesley Centers for Women.

In it, McIntosh described an “invisible knapsack” of advantages she experienced by being white in the United States. Those advantages including being able be rent or buy housing wherever she wanted, not being stopped by police because of her race, or seeing people that looked like her on television.

Her essay and the term are often used in discussions of diversity.

But the term is problematic for Christians, says Litfin, because he believes white privilege implies that being white in America is sinful. That kind of collective sin doesn’t apply to Christians, his letter argued, as they are only responsible for their own actions.

“Collective sin was operative in the covenant community of Israel, such as with Achan (Joshua 7),” he wrote. “However, with the arrival of the New Covenant, individuals now stand or fall before God for their own actions (Jeremiah 31:29-30). …Therefore, an entire race should not be held accountable for the sins of individuals. It doesn’t work like that anymore.”

He also argues that the term “can be an unloving use of the power of naming,” “can display a critical spirit that misconstrues reality by highlighting only the negative,” and “can blind us to the cry for social justice from the white oppressed.”

In an email, Litfin said that his concerns have been misunderstood.

“My letter was never intended to deny racism or the unjust disadvantaging of some people. Of course such sin exists in a fallen world,” he said in an email to CT. “I simply wanted to serve my community with some reflections from Scripture about how we should talk about it.”

Litfin agrees the ideas behind the concept of white privilege are worth discussing. But the term is flawed, he said.

“I don’t think we can say skin color automatically gives privilege in our culture. Sometimes it does,” he said. “But what about the white 12-year-old girl who has been sex trafficked? She has no privilege.”

The professor also argued that privilege should be admired and not scorned, since it’s often earned by hard work and prudent decisions. He pointed to his grandfather, an immigrant businessman who “scrimped and saved,” and his father, Duane Litfin, who was the first in the family to go to college and later became president of Wheaton College. Their actions paid off in the future long term.

“This certainly gave me privileges—but that is something God celebrates!” Litfin wrote.

Thabiti Anyabwile, pastor of Anacostia River Church in Washington, D.C., agrees with Litfin, at least in part.

Privilege isn’t a bad thing, he said. It can be used for good. But it also has consequences.

Anyabwile, who has written forcefully about recent racial tensions in the US following the death of Michael Brown and Eric Garner, said he’s not attached to the term white privilege.

He doesn’t see it as a moral judgment against white people. And it doesn’t mean that “every white person was born with a silver spoon in their mouth,” he said.

Instead the term describes a reality in American life that should be acknowledged, no matter what term is used.

“If you are a person of white skin color, you have certain advantages,” he said. “There is a currency that comes with that. We need to be able to describe that reality.”

Diversity experts at Christian colleges agree.

The term white privilege is a useful tool, because it describes a social reality in a helpful way, said Tali Hairston, director of the John M. Perkins Center for Reconciliation, Community Development, and Leadership Training at Seattle Pacific University (SPU).

Hairston said that many of the school’s white students haven’t ever had to think about their race or haven’t experienced any discrimination.

That’s privilege in a nutshell, he said.

At Seattle Pacific, talking about diversity and privilege is an act of kindness, said Hairston. It’s meant to help students of every background understand the world around them better.

For some majors at SPU, such as pre-med, discussions about privilege are mandatory. Students who are going to be doctors need to develop their cultural competency, because they’ll worth with people from all backgrounds, said Hairston. Understanding privilege will help them do that.

He said that students from white evangelical backgrounds in particular often need remedial cultural literacy so they can understand the world from other people’s point of view. That’s a wise and a Christian thing to do, he said.

“They are trying to overcome a deficit of cultural literacy,” he said. “If you were raised in white evangelical culture, you have not had to understand this.”

There’s also a spiritual aspect to discussions of privilege, argues Christena Cleveland, associate professor of reconciliation studies at Bethel University in St. Paul, Minnesota. She believes that unacknowledged privilege hampers spiritual growth in students.

“Privilege is poison,” said Cleveland, “because it keeps us from connecting with God and others.”

Cleveland uses the term white privilege as a starting point for discussion. This week she planned to have her students write a response to Litfin’s letter to the editor.

Cleveland argues that it’s an important phrase to use. If students only talk about racism or the disadvantages of some ethnic groups, she said, they’ll miss the big picture.

When some groups are disadvantaged in a culture, other groups gain an advantage, she said.

That’s not an easy thing to grapple with, especially for students from privileged background. They’ve often benefited from unearned advantages, said Cleveland. Coming to grips with that can leave them angry and confused.

She recounted a story told by one of her colleagues, in a discussion about diversity. A white student asked, “Are we inherently sinful because we are white?”

“He said, ‘No, you are not sinful because you are white—but you have inherited a sin because you are white. The question is, ‘What are you going to do about it?’” said Cleveland.

Regardless of what term they use, Christians will continue to grapple with questions about diversity, in large part because of the American church’s demographics shifts.

About 7 out of 10 Americans over age 65 identify as white Christians, according to data from the Public Religion Research Institute. Those white Christians outnumber Christians of color of their generation by about 5 to 1. Among American ages 18 to 30, about a third (32%) identify as Christians of color, while only one in four (25%) are white Christians.

As a more diverse groups of Christians come into their own, the culture and power structure of the church will change.

Anyabwile believes that for some Christians, growing diversity is seen as a threat to what had been a “white-defined” way of life in the US.

“That’s what makes the debate so pitched right,” he said.

Getting past that fear, he said, will help the church better fulfill its mission.

One places where this new demographic reality has come to life is at Nyack College, which has campuses in New York City and Rockland, New York. It’s one of the most diverse Christian colleges in the country. Only one in five students—and about half of the faculty—are white, said David Turk, the school’s provost.

For most of its history, most of the students at Nyack were white. That changed in the late 1980s, when the school started recruiting students from New York City. By 1992, about 40 percent of the students were minorities.

The demographic change caused tension, said Turk. Some of the Hispanic students on campus thought professors giving special privileges to white students. Many of those concerns went away over time, especially as the faculty became more diverse.

Turk says that most Christian colleges today will have to learn to discuss hard questions, like the topic of white privilege, because of demographics.

“The demographic change that hit Nyack 20 years ago will soon be hitting the rest of the country,” he said.

Even when they become diverse, Christian colleges will still have to have hard conversations about race and privilege.

“This is a long-term process,” Turk said.

Back at Moody, the controversy over Litfin’s remarks continues over social media, under the hashtag #mbiprivilege.

Embrace, the student group, planned to host a lecture on April 30 entitled “White Privilege: A Sacred Legacy of America’s Civil Religion” by Moody theology professor Michael McDuffee.

Moody’s president said the school is working on becoming “more inclusive and welcoming to students and staff of color.”

“For the past two years, I have personally led a task force which has been charged with developing recommendations and strategies to reach this goal,” Nyquist wrote. “Some of the changes set forth by this group have already been implemented, such as hiring more ethnically diverse faculty and appointing more ethnically diverse trustees.”

More work has yet to be done, he added.

Lebo Pooe, a senior from South Africa, is hopeful about the school’s future, despite the recent conflict.

“The notion that white privilege is not worthy of Christian discourse is extremely hurtful,” she told CT in a phone interview. Discussion of race and privilege are difficult at first, she said, “but only for a season.”

“The more we rub up against each other, the more a beautiful unity emerges.”

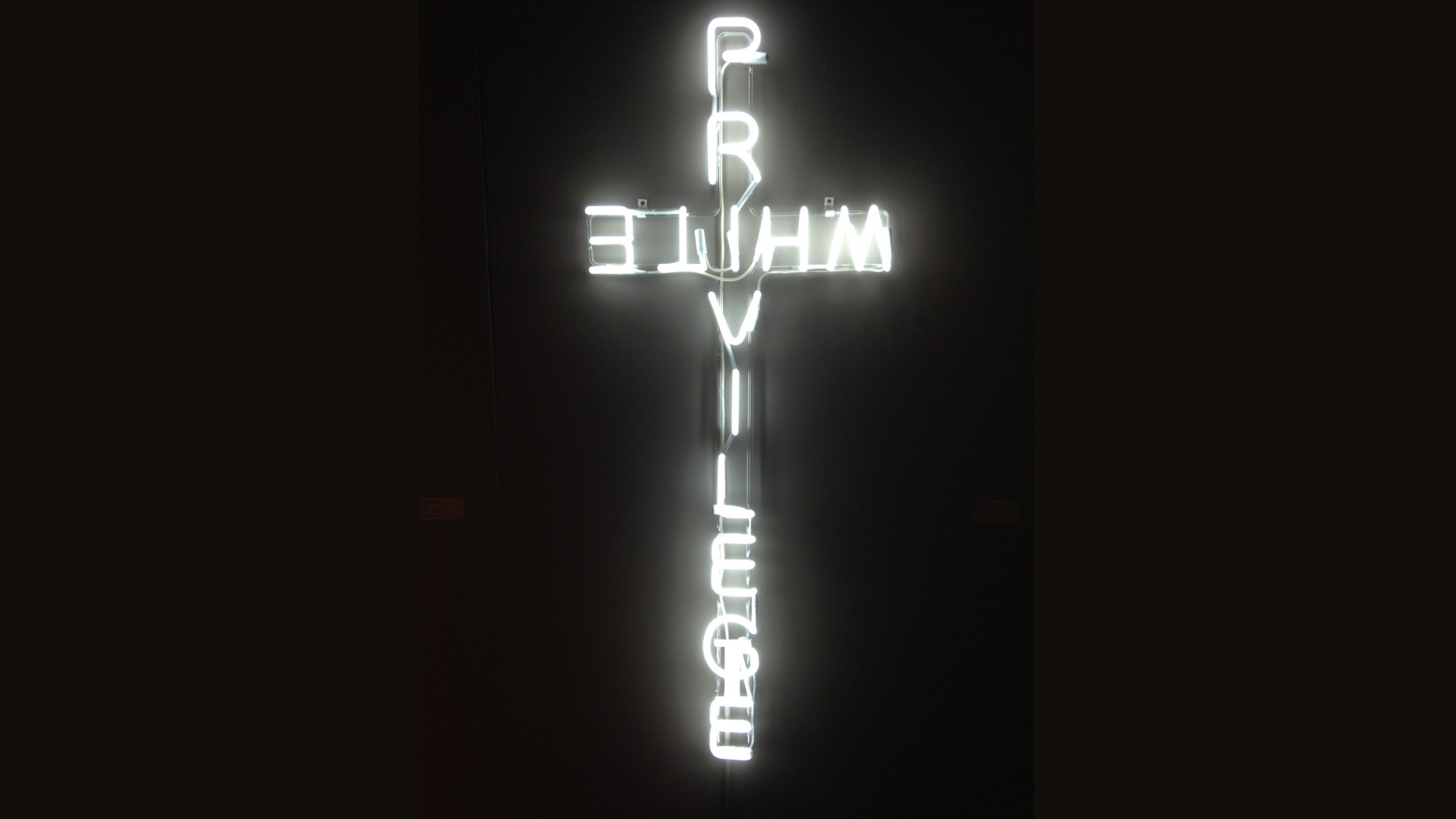

Image: "Just Sayin'," by Ti-Rock Moore, photo by Bart Everson.