In this series

When it comes to balancing the rights of religious and LGBT individuals, there’s a big difference when lawmakers versus judges make the attempt.

The latest case studies: Indiana and Utah.

On Wednesday, Indiana became the 20th state to pass a state-version of the federal government's Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA). Governor Mike Pence said the law will protect business from laws that might require them to violate their faith. Critics fear it will encourage discrimination against gays and lesbians. (An appeals court lifted Indiana's ban on same-sex marriage last October.)

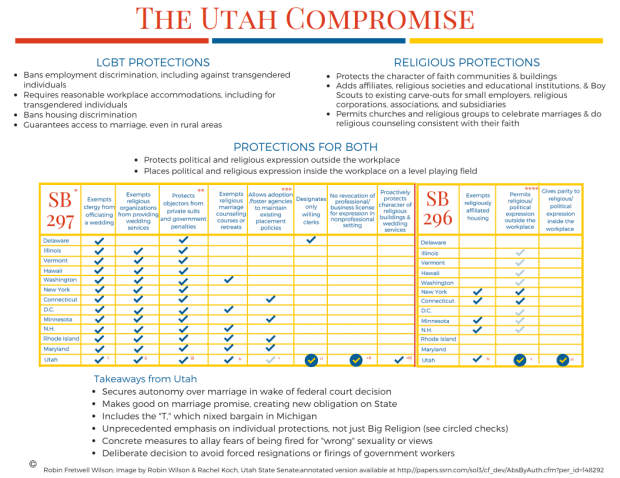

In contrast, last week—in an unprecedented compromise—Utah passed two bills: one banning discrimination against lesbians, gays, bisexuals, and transgender people; and on protecting the rights of those who object to same-sex marriage on religious grounds.

“It’s a good deal,” said University of Illinois law professor Robin Fretwell Wilson, who helped Utah legislators pass the compromise. “Both for gay people and for believers, this is a whole new level of protection we haven’t seen before.”

The RFRA laws limit the government from placing a “substantial burden” on the practice of religion. It’s a complicated approach, said Wilson, requiring a four-fold test to determine if a government’s action was legal.

Wilson said RFRA works best in clear cases of laws that clash with religion, such as laws that ban steel wheels on Amish buggies or bans on religious symbols at cemeteries. But RFRA is not an effective way to deal with the social changes caused by legalized gay marriage, she said.

“If I want assurances about what I’m permitted to do and not do in a time of great social change,” said Wilson, “I don’t want a RFRA. I want an exemption.”

The downside of Indiana’s approach is that it pits religious groups against advocates for same-sex marriage, Wilson argues. Utah’s approach requires the government to protect both groups.

Utah’s set of bills offered brand-new protections to people on both sides of the same-sex marriage debate. All religious and political expression of all views inside the workplace are protected equally.

The compromise was supported by the Mormon Church and other religious groups.

“Here we make history, said Republican Steve Urquhart, a state senator who co-sponsored the bill. “We have shown that LGBT rights and religious liberties, they are not opposites, they are not mutually incompatible, they are pillars in the pantheon of freedom.”

Utah’s two bills lay a fresh emphasis on individual rights. It includes a new way to deal with cases such as a government clerk who objects to processing marriage licenses for same-sex couples.

Before the bills passed, a clerk could get a conditional exemption handling licenses only if that did not exemption did not cause a hardship for a same-sex couple. Now a clerk could get an exemption, and it would be up to the state for find a replacement clerk to handle the marriage license, said Wilson.

Utah’s bargain was enacted just five months after the state was ordered by the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals to recognize same-sex marriage, and proves that working together through legislation is a better way to protect religious freedom than a knock-down fight to ban same-sex marriage altogether, Wilson said.

CT covered this approach last year in examining evangelicals’ favorite same-sex marriage laws. In January 2014, CT asked a group of legal scholars on the forefront of advising lawmakers on religious exemptions to assess which of the 12 existing state SSM laws at the time offered the best protections. The best: Maryland and Rhode Island. The worst: Delaware. [Download detailed chart.]

Christianity Today

Christianity Today“[Battling to ban same-sex marriage] is not going to work,” she said. “You want to extend a fig leaf to the other side. Nobody should be trying to hold the other guy down.”

Though the compromise has been hailed around the nation, the ability of other states to follow Utah’s lead is up for debate.

“Negotiators didn’t have as big a gap to close as in some other places,” wrote Jonathan Rauch of the Brookings Institute, warning that “Utah won’t be a template for other states, because no such template exists.”

But Wilson said other states, like Idaho, are already taking a closer look at Utah’s legislation. “I felt more hopeful out there [in Utah] than I have in years,” she said. “You can kick a ball rolling just by showing that it’s possible.”

The Mormon church’s strong hierarchical leadership made an effective partner in forging a compromise, she said. “If evangelical churches who are tired of the culture war could get together in coalitions, they could have the same effect,” she said.

Finding common ground in this culture war hasn’t been—and won’t be—easy.

Earlier this month, Charlotte, North Carolina, narrowly rejected a proposal that would have addressed accommodations based on sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression. One, a proposal to let transgendered people use whichever bathroom they liked, drew the ire of many evangelicals, including Franklin Graham.

“It’s not only ridiculous, it’s unsafe,” he wrote on his Facebook page. “Common sense tells us that this would open the door, literally, to all sorts of serious concerns including giving sexual predators access to children. It violates every sense of privacy and decency for people of both sexes, adults and children.”

In October, evangelical voices such as as John Piper, Russell Moore, and Eric Metaxas decried the Houston mayor’s subpoena of the sermons of five pastors in the city. The targeted Houston pastors were involved in a political action group that organized a drive to get the city to put a proposed ordinance—one that would allow transgender people access to the bathroom of their choice, among other things—up to a vote. After public outcry from both ends of the religious and political spectrum, the mayor rescinded the subpoenas.

“Peter and John didn’t stay, all the time, in the temple court preaching Jesus. But they didn’t cease while they were under orders to do so (Acts 4:21-23),” Moore wrote. “Religious liberty isn’t ours to give away to Caesar, and soul freedom isn’t subject to a subpoena from City Hall.”

CT has closely followed the same-sex marriage debate, including the failure of Utah’s same-sex marriage ban and the first time state bans on same-sex marriage were upheld by an appeals court.

CT also noted a New Mexico ruling that wedding photographers can’t turn away same-sex couples and an Arizona bill that would have let religious beliefs stand as a defense for sexual discrimination. Americans are evenly split on whether they believe business owners should be forced to provide flowers, food, or photography for same-sex weddings.

[Photos courtesy of Shaun Fisher – Flickr and Richie Diesterheft – Flickr]