If you were to describe how a caterpillar turns into a butterfly, it would probably sound a lot like Eric Carle’s The Very Hungry Caterpillar. You might not include his bits about chocolate cake, lollipops, sausages, and pickles—but you know he gets it basically right. A caterpillar hatches from an egg, eats until it gets really fat, then creates its chrysalis shell. After a few weeks it pushes its way out and becomes “a beautiful butterfly”!

But wait, how did the caterpillar turn into a butterfly?

You have to love the answer at kidsbutterfly.org: “This is not easy to explain.” It goes on to try: “You can say that inside the chrysalis the caterpillar changes clothes and turns into a butterfly. (An esoteric explanation: Inside the chrysalis the caterpillar structures are broken down chemically and the adult's new structures are formed.)”

Right. But getting “broken down chemically” isn’t exactly compatible with “changing clothes,” unless you’re talking about a sartorial stew. The most frequently used word to describe the inside of a chrysalis at its most transformative moment as a caterpillar becomes a butterfly is soup. There’s no caterpillar carefully attaching wings to its back, or half-caterpillar half-butterfly hybrid. It’s just a wet, gooey mess in there.

The caterpillar’s body has melted, special enzymes dissolving tissues as the creature digests itself. Its legs? Gone. In fact, if a caterpillar lost one of its legs during its life, not to worry: The butterfly will have six anyway upon its emergence. The caterpillar’s eyes? Liquefied into the protein sludge, to be remade into some new part of the butterfly. The antennae? Gone: New ones are being grown.

It’s only been since 2013 that we’ve been able to actually watch a caterpillar turn into a butterfly. With 3D CT scans, British researchers watched as some caterpillar organs survived the enzyme breakdown. The guts didn’t dissolve, but instead changed—dramatically and quickly. The caterpillar’s breathing tubes, meanwhile, hardly changed at all.

Before these new experiments with CT scans, researchers had mostly applied what they knew from fruit fly and blowfly metamorphosis, as well as what they’d learned from destroying chrysalises and looking inside. The new research doesn’t significantly change what we know about metamorphosis—it just gives us a few more details, confirmations, and some great visuals.

But earlier efforts to watch the transformation were not so successful.

Eels from Mud, Flies from Corpses

From early classical writers to the 1600s, Westerners believed that small creatures like insects did not reproduce sexually. Instead, they believed that small creatures were simply born out from the dead remains of unrelated animals, or out of inanimate matter like earth and water.

Aristotle’s view that terrestrial elements could combine with “vital heat” to spontaneously generate life dovetailed with Christian readings of God’s commands in Genesis. “Let the earth bring forth the living creature” (1:24) and “Let the waters bring forth abundantly the moving creature that hath life” (1:20, KJV) were taken literally.

“If there are creatures which are successively produced by their predecessors, there are others that even today we see born from the earth itself,” Basil of Caesarea, one of the greatest theologians of the early church, preached in one Genesis sermon. “In wet weather she brings forth grasshoppers and an immense number of insects which fly in the air and have no names because they are so small; she also produces mice and frogs. In the environs of Thebes in Egypt, after abundant rain in hot weather, the country is covered with field mice. We see mud alone produce eels; they do not proceed from an egg, nor in any other manner; it is the earth alone which gives them birth.”

Basil’s sermon isn’t just an example of longstanding views on spontaneous generation. His comment that insects “have no names because they are so small” is telling, too. Bugs didn’t attract much attention before the late 1600s, except in cases where they provided metaphors: the “king” bee provided a God-given model of monarchic rule. Ants were praised for their industriousness, in accordance with Proverbs 6. Locusts had several biblical connotations.

And butterflies were a sign and evidence of the resurrection.

“As it is miraculous to our eyes but at the same time clearly evident, that from dead caterpillars emerge living animals, so it is equally true and miraculous that our dead and rotten corpses will rise from the grave,” wrote Johannes Goedaert.

Goedaert (1617–1668), a Dutch painter who was one of the first Europeans to argue for more attention to the broader world of insects, invariably is described by historians as “pious.” Like nearly everyone else, he saw butterflies as metaphors and a promise of resurrection. But unlike most others of his day, Goedaert found the whole world of insects a wondrous menagerie pointing to God’s glory.

“[T]here is no creature so small, or by the attentive observation thereof one can find immediate cause and ample reasons to glorify God, and wonder at his marvelous wisdom and providence,” he wrote. “The truth of this I have discovered by the observation of worms, caterpillars, maggots and other crawling animals.” After all, he noted, the Psalmist wrote that God rejoices in all his works (Ps. 104:31), including “things creeping innumerable, both small and great beasts” (v. 25, KJV).

The painter observed his subjects closely, from egg to caterpillar to butterfly. He was impressed by how specific caterpillars generally created the same kinds of chrysalises, which produced the same kinds of butterflies. He still thought of them as different animals: butterflies emerging from the corpses of dead caterpillars the way maggots seem to emerge from dead cattle. But one observation surprised him: He watched as two identical caterpillars of the same apparent species “died.” But out of one chrysalis, “a Butterfly is produced.” Out of another, “82 Flyes.”

“These things I have had the experience of, and Observed them, not without admiration because it seems besides, if not against the usuall course of Nature, that from one and the same Species of Animals, an Offspring of different species should be gendred.”

Unbeknownst to Goedaert, what had actually happened was that a parasitic wasp had laid eggs inside or on top of one caterpillar before it pupated, and the wasp larvae had fed on its host inside the chrysalis. But for a while it seemed like anything was possible—not only could one animal emerge spontaneously from a dead animal of a different species, but it wasn’t always the same kind of animal emerging!

This idea, that caterpillars and butterflies are two different species, was soon successfully challenged. (More on that in a moment.) But the argument has persisted.

In 2009, the prestigious journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) published an article by British zoologist Donald Williamson. He argued that butterflies and caterpillars essentially evolved separately, as two different organisms—and that somewhere along the line the two species accidentally but successfully mated.

The theory makes a lot of sense, University of Vermont biologist Bernd Heinrich wrote in his 2012 book on animal death, Life Everlasting. During metamorphosis, caterpillar DNA is essentially “turned off,” and butterfly DNA, which had been suppressed, is “turned on.” Heinrich writes:

A new theory claims that because the metamorphosis . . . is so radical, with no continuity from one to the next, that the adult forms of these insects are actually new organisms. . . . In effect, the animal is a chimera, an amalgam of two, where first one lives and dies and then the other emerges. . . . Regardless of how it came about, there are indeed two very different sets of genetic instructions at work in the metamorphosis . . . and these are as different as different species, or even much more so. They thus represent a reincarnation, not just from one individual into another, but the equivalent of reincarnation from one species into another.

As Heinrich notes, it’s an aberrant view among biologists. Williamson was ridiculed for proposing it, and PNAS quickly published a rebuttal (but not a retraction).

The Butterfly Inside

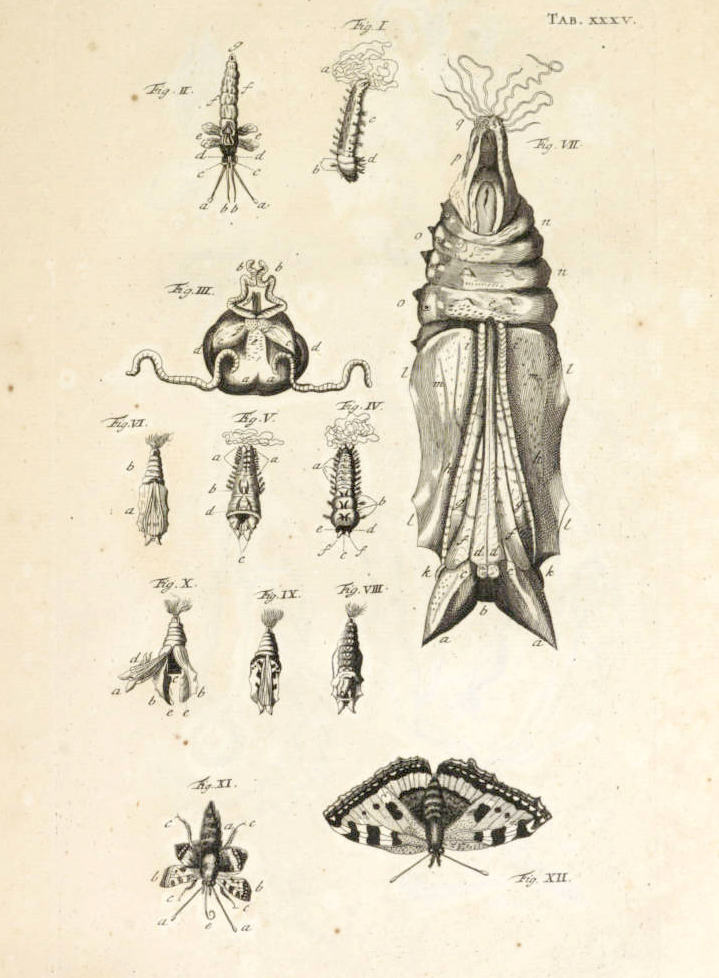

In the 1600s, within a year of Goedaert’s Metamorphosis, another Dutch butterfly lover had found a simple way to convince people that the caterpillar and the butterfly were indeed the same animal: Johannes Swammerdam simply cut open a caterpillar that was preparing to become a chrysalis. Inside were rudimentary wings and legs—“a Butterfly enclosed and hidden in a caterpillar, and perfectly contained within its skin.”

Yes, inside the chrysalis there’s a soup. And tissues from the caterpillar are liquefied and turned into parts of the butterfly—but at the same time, the parts of the butterfly have already started growing inside the caterpillar, even before it enters its chrysalis.

Swammerdam’s finding was a tremendous blow to the theory of spontaneous generation, which he saw as “the straight road to atheism . . . for if generation were at random, man could be generated in the same way, as some have been rash enough to write.”

Random chance doesn’t decide whether a butterfly or 82 flies emerge from a chrysalis, Swammerdam wrote. “All God’s works are based on the same rules.”

“A worm or caterpillar does not change into a pupa, but becomes a pupa by the growing of parts; so also this pupa, we may add, afterward does not change into a flying beast, but . . . becomes a flying beast,” he wrote. The changes a caterpillar goes through to become a butterfly “are nothing else than those of a chick, which is not changed into a hen, but becomes a hen by the growing of its parts.”

But if Swammerdam thought his research was a blow against atheism and random chance, he also recognized that his work undercut efforts to use butterflies “to explain the resurrection of the dead.” Good riddance, he said:

This clearly exposes the error of those who have wanted to prove the resurrection of the dead by these natural and intelligible changes, which not only goes entirely beyond the order that can be observed in nature, but has no parallel in nature either. . . . These small animals do not die, as man does, in order to rise again; all that happens to them is that their limbs are improved.

In short, the resurrection is a promise of the world to come that we can’t imagine based on what this world shows us. Caterpillars suffer only an “idle and imaginary death.” (Though, with a possible wink, he did grant it “worthy of notice that when I viewed a deformed worm . . . changed into a fly it was in no way deformed, its body being then perfect after its change, or rather its resurrection.”)

For Swammerdam, taking away butterflies’ literal resurrections didn’t make them less of a [tool] to see God’s glory and work in the world—it made them more of one, since they indicated that God was revealing himself in the smallest details of the smallest creatures.

“Who is not delighted and convinced when he rightly considers these wonders of God?” he wrote. “[They show] that the omniscient and good God is understood and known from his visible things, in that he reveals his invisible things so powerfully to us in the visible ones, so that his eternal godhead is displayed there radiantly; so that no one should be pardoned in his sin who has received the law of nature, the law of Moses and that of the gospel; after which all peoples will be judged, whether they shall be acquitted or condemned.”

Nor did Swammerdam think the metaphors these animals offered were useless. On the contrary, his Bible of Nature is full of moral instruction, theological reflection, and spiritual asides that follow from his biological insights. The short lifespan of mayflies should remind us of how fleeting our own lives on earth are, he argues. Rhinoceros beetles’ difficult early stages of life should remind us of Paul’s promise that “our present sufferings are not worth comparing with the glory that will be revealed in us.” And even fly metamorphosis can be a visible reminder of “how near our resurrection and reformation is” and “the real metamorphosis of the human mind . . . [when] we cast off the ancient dirt of avarice, pride, and envy, and change those vile passions for the most sweet and gentle love of Christ.”

The humblest of animals may prompt these insights, Swammerdam says. And taken together, one can’t help but be overwhelmed by “the inscrutable God and the unfathomable Creator, wonderous and matchless in his works.”

But still, Swammerdam had favorites: “There is nothing in the world of nature which deserves greater admiration than the change of a caterpillar into a winged insect.”

Ted Olsen is co-editor of The Behemoth and managing editor of Christianity Today.