On the stage of Waco Hall, I was worried that the world was about to come to an end way too soon and I just wasn’t ready. In 1972, I saw—for the first time—Andraé Crouch and the Disciples performing “The Blood Will Never Lose Its Power,” “Soon and Very Soon,” “My Tribute,” “Through It All,” and “Bless His Holy Name.” I was both mesmerized and a little frightened.

I had been a fan of black gospel music since childhood. But as a freshman at Baylor University, I knew that this was something different. I just knew. And it was something different for Jesus Rock (the term “contemporary Christian music” or CCM wasn’t in wide usage back then).

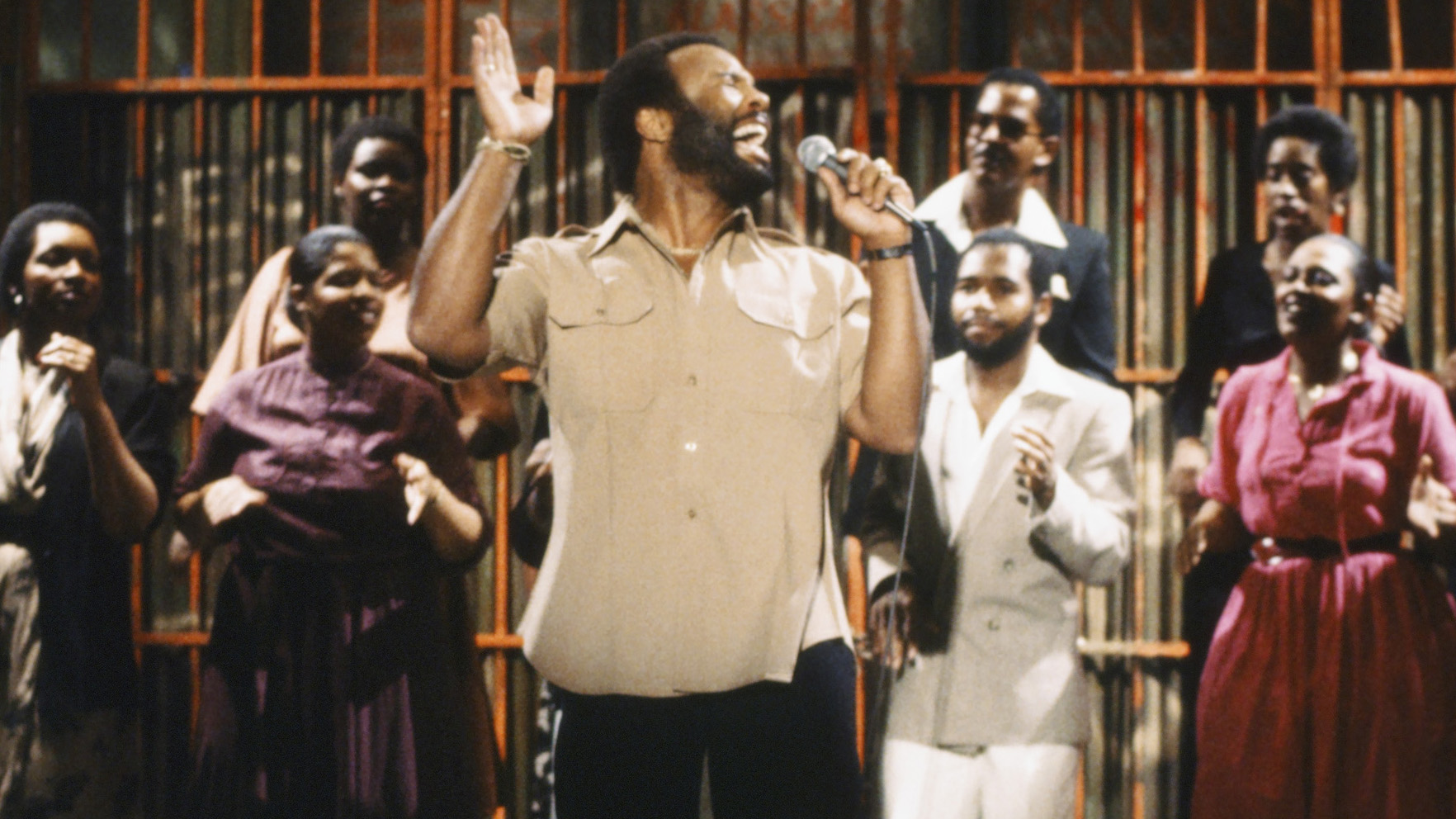

Crouch was an innovator, a path-finder, a precursor in an industry noted for its conservative, often derivative approach to popular music. He combined gospel and rock, flavored it with jazz and calypso as the mood struck him and the song called for it, and is even one of the founders of what is now called “praise and worship” music. He took risks with his art and was very, very funky when he wanted to be. Tonight he died at age 72 from complications from Saturday's heart attack.

Amy Grant may have made CCM popular; Andraé made it sound great.

Naturally, years later, when I became gospel music editor for Billboard magazine, one of my first columns was on Crouch. When I wrote People Get Ready: A New History of Black Gospel Music, Andraé was featured in his own chapter (along with Alex Bradford and James Cleveland).

Amy Grant may have made CCM popular; Andraé made it sound great.

When Michael Jackson or Madonna or Quincy Jones needed a gospel song or a gospel chorus, they called Andraé. That’s his music on the soundtrack to The Color Purple (where he earned an Oscar nomination), the Broadway musical The Lion King, and the pop songs “Man in the Middle” and “Like a Prayer.”

Not surprisingly, great swathes of the religious audience voiced their displeasure. How dare he combine Saturday night with Sunday morning? As he told interviewers, the criticism from the church sometimes hurt, but he soldiered on.

Then again, we’ve never been shy about shooting our wounded in CCM, have we?

So, with his untimely passing, what should you know about the musical legacy of Andraé Crouch? Besides the fact that he wrote the standard “The Blood Will Never Lose Its Power” (commonly called “The Blood”) at age 14, of course. Not to mention that his first gospel group included Billy Preston, Edna Wright (later with the Honeycombs), Gloria Jones (later a Motown songwriter), and his twin sister Sandra Crouch (who would have a wonderful gospel career as well).

And perhaps you already know that Elvis recorded one of his songs, that Paul Simon’s live show included “Jesus is the Answer” for years, and that his compositions are featured in a host of white and African American hymnals.

But what you need to know is that Andraé Crouch was musically and lyrically fearless, endlessly inventive, always searching for better ways to express the gospel in music.

Perhaps that fearlessness came from growing up in the Compton area of Los Angeles. Perhaps it came from a life spent in the Church of God in Christ, the most musically adventuresome of all Protestant denominations, which embraced electric guitars and drum kits when other denominations were splitting over whether or not to have pianos in the sanctuary. Or perhaps it came from living in the rich musical stew that was Southern California in the post-World War II years.

When Crouch founded the Disciples in the early 1960s, it was another all-star aggregation with sister Sandra, percussionist Bill Maxwell (later a noted music producer), horn player Fletch Wiley, and Danniebelle Hall (another gospel soloist). The Disciples also just so happened to have both black and white members. Not surprisingly, various members have told of frightening experiences the band suffered in the South, including a run-in with the KKK. Like Sly and the Family Stone, concert-goers, black, white, Christian or secular, had never heard or seen anything like them before.

And, as a freshman at Baylor, neither had I. Yes, I had been to Explo 72 in Dallas, but Kris Kristofferson, Love Song, and Larry Norman hadn’t prepared me for this. An Andraé Crouch and the Disciples concert was explosive, unpredictable, decidedly evangelical, and it had a great, unrelenting beat. That night, the air in the drafty old hall appeared to shimmer, like it was going to explode. It seems funny now, but I was afraid that the Second Coming was nigh. Seriously. That’s how much the concert moved me.

Like most kids from the ’60s and early ’70s, I was really into music. While my passion lay in gospel, soul, and R&B, I also loved the white artists who sounded black—Steve Winwood and Van Morrison. That weekend, I began adding Andraé Crouch and the Disciples records to my collection.

My favorite was Live in London, which boasted an extraordinary (for the time) cover—an air-brushed Mothership-sized piano, hovering above the United Kingdom, with the LP title and band name emblazoned in lights. I loved it. Controversial, ambitious, aggressive, Live in London featured old-school gospel, rock, R&B, even praise and worship. I played it as often as I played my Black Sabbath and Wilson Pickett LPs. Today, numerous gospel artists still praise Live in London as the most influential piece of vinyl from their past. It is certainly hard to imagine a Kirk Franklin or a Tye Tribbett without a Live from London.

And now I’m 60. Andraé’s passing makes me a little older. It makes contemporary religious music a little more washed-out, flat, and placid. Andraé was all about joy. The joy of his salvation and the joy of creation. His prodigious gifts challenged and transformed an industry.

Still, I’m not ready for Live in London right now .

Instead, I’m turning to the solo albums Just Andraé and Another Live. The Rev. Stephen Newby calls these more introspective, more musically diverse LPs the Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band of gospel music. I didn’t “get” them at the time. I wanted more COGIC-infused thumping bass and drum rave-ups.

But today, Just Andraé, in particular, speaks to me. I’m recalling the first time I heard “In Remembrance,” “Come on Back, My Child,” “If Heaven Was Never Promised to Me,” the chilling “Lullabye of the Deceived,” and, of course, “Bless His Holy Name.” Stephen Newby recently helped me to see these compositions as a song-cycle of uncommon insight, of uncommon depth. It’s a mature statement by an artist at the peak of his powers. And it’s a fitting coda to a life well lived, a musician who seemed to have a special gift for combining the sacred text with the profane beat:

But if heaven never was promised to me,

Neither God's promise to live eternally,

It's been worth just having the Lord in my life.

Living in a world of darkness,

You came along and brought me the light.

Robert Darden is an associate professor of journalism, public relations & new media at Baylor University. His latest book is Nothing But Love in God’s Water: Black Sacred Music from the Civil War to the Civil Rights Movement (Penn State University Press, 2014).