Like more than 1.5 million others, I’ve spent the last several weeks listening to Serial, a podcast that debuted in October from the producers of the popular public radio program This American Life. The first season of Serial investigates the 1999 murder of a Baltimore teen, Hae Min Lee. Adnan Syed, her ex-boyfriend, was charged with the crime the following year and is currently serving a life sentence, though he maintains his innocence.

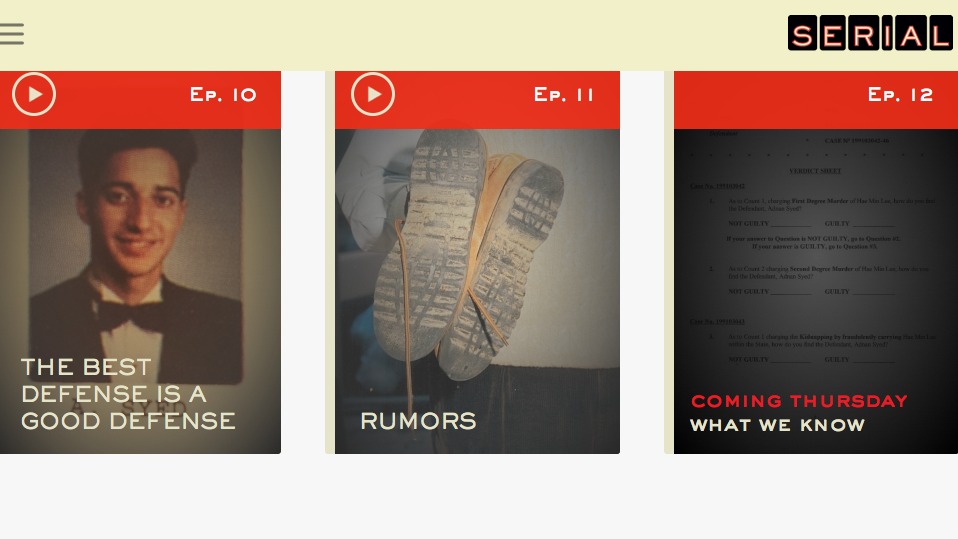

Each new episode debuts on Thursday mornings. In between installments, avid listeners poll friends and strangers: “Have you been listening to the show? Do you think he’s guilty?” Everyone I talk to has an opinion. The show wraps up its 12th and final episode today, so well received that it’s already secured funding from sponsors and listeners for a second season. As The Wall Street Journal put it, “in the normally low-profile world of podcasting, ‘Serial’ is a certified sensation—a testament to the power of great storytelling.”

As a writer and editor, I appreciate well-researched and beautifully told stories. Serial has both. Creator and host Sarah Koenig spent more than a year examining the case before the first episode aired. She carefully presents new evidence each week along with interviews with Syed in prison, his former classmates, and legal experts, as well as her own shifting opinions.

As Serial surged to become the most popular podcast in history, I joined the chorus of voices wondering why audiences are so drawn to the show. After all, This American Life—done in a similar style, but with thematic, hour-long episodes each week—has never reached the fervor Serial has as a standalone podcast. What’s the difference?

As its name indicates, Serial tells bits of the story week by week, leaving listeners desperate for more answers. Instead, we get more details and, thus, more questions. Koenig says it best in last week’s episode, titled "Rumors," which examined Syed’s character and questioned whether he might be a psychopath. Koenig asks:

Can you tell, really? Can you tell if someone has a crime like this in him? I think most of us think if we know someone well, we can tell. We act as detectives all the time, gathering evidence. Certain scenes we remember or the look on someone’s face of that thing he said when he got mad. Then we act as a judge of character—this is just a human thing. But of course it’s slippery because it’s so subjective. One person’s evidence of good character is another person’s evidence of questionable character.

Our interest in Serial, and the story of Adnan Syed, rests in our innate desire for a conclusion to the story—and a just, fair, and right conclusion at that. We hate the idea that a guilty man still won’t admit his crime, and we really hate than an innocent man might be sitting in prison for a crime he didn’t commit. Despite Syed’s conviction in 2000, podcast listeners are analyzing new and old evidence alongside Koenig, and most of us are unsatisfied that we can’t tell whether Syed is a good guy or a bad guy.

Last week, Koenig announced that today’s episode of Serial would be this season’s last. Despite her research, it doesn’t seem she’ll reach any strong conclusions. For some listeners (including me) that’s frustrating. People are disappointed that the show won't declare whether Adnan Syed is guilty—as if it’s Koenig’s job to prove what took place after school one day 15 years ago in Baltimore. Fictional CSI shows get to explain exactly what happened and exactly why the killer did it. In real life, we don't get that sense of finality.

At some level, we all want the satisfaction of neatly packaged conclusions. But our willingness to hear out real stories with open endings reveals something greater to us. Through a lack of resolution, we face the frustration, mystery, and open endings that are an inevitable reality in our lives. Our collective craving for truth and justice in Hae Min Lee’s murder is a small reminder of a yearning that only heaven can satisfy.

As I continue to consider whether a teenage Adnan Syed could be capable of his ex-girlfriend’s murder, I’m reminded that someday we will no longer have to act as detectives, weighing and wondering the good and the bad for ourselves. In Revelation 19:1-2, in a passage referring to the fall of Babylon, the Bible reads, “Hallelujah! Salvation and glory and power belong to our God, for true and just are his judgments.”

In his book Mere Christianity, C. S. Lewis writes, “What can you ever really know of other people's souls — of their temptations, their opportunities, their struggles? One soul in the whole of creation you do know: and it is the only one whose fate is placed in your hands. If there is a God, you are, in a sense, alone with him.”

As Christians, we should continue to strive for truth and justice in this world. We have an obligation to. But our systems are imperfect, and so are we. We will get things wrong. We won't be certain. We don't know how to make it all right.

Yet there is a time coming when we won't be compelled to form our own opinions and judgements, nor will there be thieves who go unpunished or innocent people who sit in prison. Our longings for truth and justice will be fully satisfied by the power of our Great God who knows all, and is all.

Lesley Sebek Miller is editor of Kidaround Magazine. She blogs at http://barefooton45th.com and tweets as @LesleyMiller.