The Bible’s had a busy year in Hollywood—from Noah in February to Ridley Scott’s Exodus: Gods and Kings this December. So perhaps it’s unsurprising that this would be the year Lifetime chose to adapt The Red Tent, Anita Diamant’s 1997 novel about the Old Testament character of Dinah, into a TV miniseries.

When Hollywood ventures into sacred waters, Christians often aren’t excited about the result. Attempts to convey Biblical narratives many times result in strong reactions and critique: either the adaptations aren’t true to the source material, or the characters aren’t behaving like good Biblical characters should.

The Red Tent is no exception. Diamant, the book’s author, has faced accusations of blasphemy for her imaginative departure from the events of Genesis 34.

If you’re struggling to remember Dinah’s story, that’s likely because there’s not a lot there. It’s told in a single chapter. Dinah, the daughter of the patriarch Jacob and his first wife Leah, is violated by a city ruler, Shechem. His later request to marry her results in her brothers’ demands that the males of the entire city circumcise themselves. Driven by Shechem’s persuasions, the men agree to do so, and while they are physically recovering, Dinah’s brothers slaughter the city in revenge.

Although the episode is sometimes read as a rape, Diamant saw something else in the story. “[The prince] doesn’t act like a rapist. He submits to what was then a very humiliating request in order to marry Dinah,” she says. Diamant used that discrepancy as a departure, reimagining the event as a love story, in which Dinah and the prince fall in love and the destruction of the city is a tragic end to Dinah’s romance and her previous way of life.

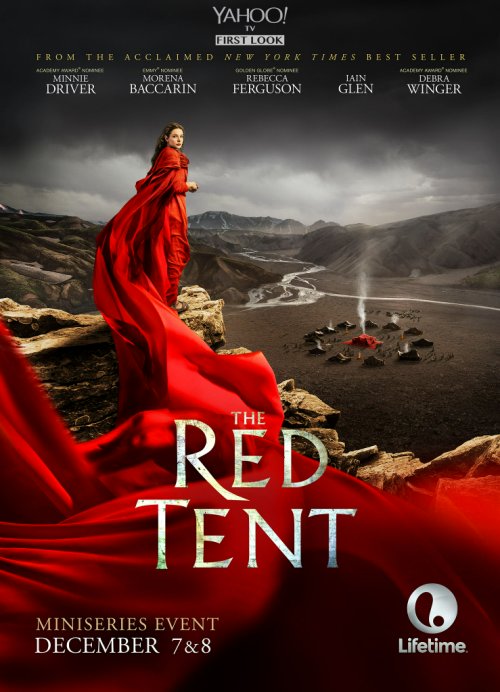

The Red Tent grew in popularity largely through religious communities. Readership spread through word of mouth—synagogue and church-sponsored book clubs, rabbis and pastors speaking about the book to congregants. Lifetime is clearly hoping to tap into that same audience with the upcoming miniseries adaptation, which premieres December 7 and 8. At a recent screening hosted at the Stephen Wise Temple in Los Angeles, the story was introduced as “epic modern midrash,” referring to Jewish commentary on the Hebrew Scriptures.

Yet the label of religious commentary is one that Diamant has resisted. She wasn’t looking to add another chapter to the Bible, or even to stay faithful to the events as depicted in Genesis. “It’s not midrash. It’s a novel,” she replied later in response to questioning. “When it came out, there was lots of comparison to the Bible, and concerns about my corrupting the text. But I have freedom as a novelist . . . My responsibility is to tell a good story.”

Reader reviews of the book are divided between those who admire the tale and those who find its depiction of Biblical characters offensive. Jacob is arrogant. There’s too much sex. Rachel and Leah participate in pagan ceremonies and prefer their own idols to Jacob’s God. And all of this in vivid detail, which seems to condone the actions rather than reprove them.

David Appleby / Lifetime

David Appleby / LifetimeIt’s not that the Bible is without any of these things—arrogance, sex, and plenty of idol worship abound, both for those outside the Israelite community and those within it. But the words of Genesis are sparser, the language more removed. It’s easier to read Jacob and Judah and Rachel as respectable and noteworthy without all the graphic details of their betrayals and lusts and idol thievery depicted so thoroughly.

And that’s just the beginning of Diamant’s departure—she freely alters and reinterprets events well known to readers of Genesis, from details as small as Leah’s “weak eyes” (in The Red Tent one is blue and one green) to the events leading up to Jacob’s marriage to Leah (a plot hatched by Leah and Rachel rather than by Laban). The Red Tent doesn’t always sit well with readers concerned about Biblical accuracy.

But in some sense, it’s the refusal to limit itself to only what’s on the Bible’s pages that makes The Red Tent such a good story. We see what took place behind the scenes in Jacob’s marriage to two sisters. We feel the uncertainties of following an unknown God without any written instructions, practices, or other believers. We walk with Dinah as she learns from her mothers about sexuality and relationships, copes with the limitations of a highly patriarchal culture, and loses people she loves.

A book like The Red Tent can force us to reflect on familiar stories in new ways. “For a lot of people, the book opened the Scripture, helped them find themselves in the text,” Diamant says. “The Red Tent gives twenty-first century readers a new perspective on ancient Scriptures. That new perspective raises questions, which can in turn, lead to a range of creative answers.”

Lifetime

LifetimeSome of these creative answers Christian readers and viewers might find objectionable. But The Red Tent reminds us that the people God used were not untouchable icons, engraved in stone as definitively as the law onto stone tablets. Rather, they were fellow creatures who often behaved quite badly—some of which is captured in the pages of Scripture, and a lot of which probably isn’t. They struggled to make sense of the world around them, and in facing similar concerns to the ones we face today, made choices that sometimes aligned with a God that would continue to reveal himself throughout history, and sometimes didn’t.

When I asked Diamant how she navigated the boundary between Bible and novel, she responded sharply: “The Red Tent is fiction, not biblical commentary. I feel no need to apologize or justify my choices as a writer. That boundary is a choice. It is not my choice.” It’s an answer that demands freedom for story, to let it say what it will, ask what it will, interpret how it will—in other words, to allow art to be art, and not Scripture, or teaching, or worship.

Yet art need not be biblical interpretation to help us look at our lives and faith with fresh eyes. When we allow it to ask difficult questions and imagine unspoken realities, it can lead to possibilities that are frightening, disturbing, or uncomfortable—but that can also open us to new ways of seeing that we couldn’t previously have imagined.

AnnaLouise Carter is a freelance writer. She lives with her husband in South L.A, where they work in community development as part of a multicultural, cross-class church.