As death approaches, he leaves his body behind. Angels usher him out of the only world he's ever known and up into a land filled with beautiful flowers and trees. He arrives at a city whose walls beam with light.

The first person he meets is Jesus, clothed all in white. The Lord's face projects a youthful radiance, and he greets the new arrival with warmth and tenderness. The visitor then encounters a parade of faces from earth. He doesn't know them, but they are all excited to finally meet him.

Eventually, this heavenly expedition ends, and he awakens back on earth. His experience is recorded in a wildly popular book read around the world.

No, this isn't the story of Colton Burpo, the four-year-old boy who supposedly traveled to heaven during an emergency appendectomy. It's the story of Saturus, a third-century Christian martyr. Saturus recorded this ecstatic experience shortly before he was brutalized by wild animals and then killed by gladiators in celebration of Emperor Geta's birthday in A.D. 209. His account is found in The Passion of St. Perpetua, St. Felicitas, and their Companions, one of the oldest Christian texts.

Most 21st-century Christians have never heard of Saturus. But Colton's experience has become something of a phenomenon. Heaven Is for Real, his father's account of the uncanny event, has become a mainstay of contemporary evangelical apologetics. It's sold over eight million copies and has recently been turned into a hit movie.

Yet Colton's story is hardly unique. Eight million people in America claim to have had a "near-death experience" (NDE), a term coined in 1975 by physician Raymond Moody. NDE patients tell eerily similar tales: a dark tunnel, a white light, a life review, and visions of unearthly worlds and ethereal beings. They also claim to have out-of-body experiences, viewing themselves from a distance, and observing events they shouldn't be able to see. It's enough to have made non-Christian philosopher Robert Almeder theorize that humans must have extrasensory perception or clairvoyance. At the very least, he concludes, NDEs go a long way toward legitimizing belief in an afterlife.

Deathbed residents aren't the only ones taking trips to supernatural realms. The history of God's people is brimming with such ecstatic experiences. In Scripture, God regularly pulls back the curtain to give chosen observers (and readers) a peak into his spiritual machinations. These experiences begin in Genesis—Jacob dreams of a heavenly ladder with God at the top, promising to care for Jacob wherever he goes—and continue all the way to Revelation—John is shown an apocalyptic vision of heaven and the future that God has in store for creation.

But turning the last page of Scripture doesn't cork the flood of ecstatic tales. From early Christian martyrs like Saturus and his co-visionary Perpetua to Christian mystics like Francis of Assisi, Julian of Norwich, and Theresa of Avila, such experiences frequent the body of Christ. Even Christian philosopher and scientist Blaise Pascal recorded a vision of ecstasy that shook him up and renewed his religious zeal. He sewed a note describing his experience to the inside of his coat:

Fire.

God of Abraham, God of Isaac, God of Jacob, not of the philosophers and savants.

Certitude, certitude; feeling, joy, peace.

God of Jesus Christ.

"Thy God shall be my God."

In this sea of ecstatic experiences, what gives Colton Burpo's story the buoyancy to float to the top of our cultural consciousness? Perhaps it finds just the right mix of preschool innocence and supernatural wonder to grab our attention. But I think it has more to do with its stated objective: To prove heaven exists.

Heaven Is for Real: Fact or Fable?

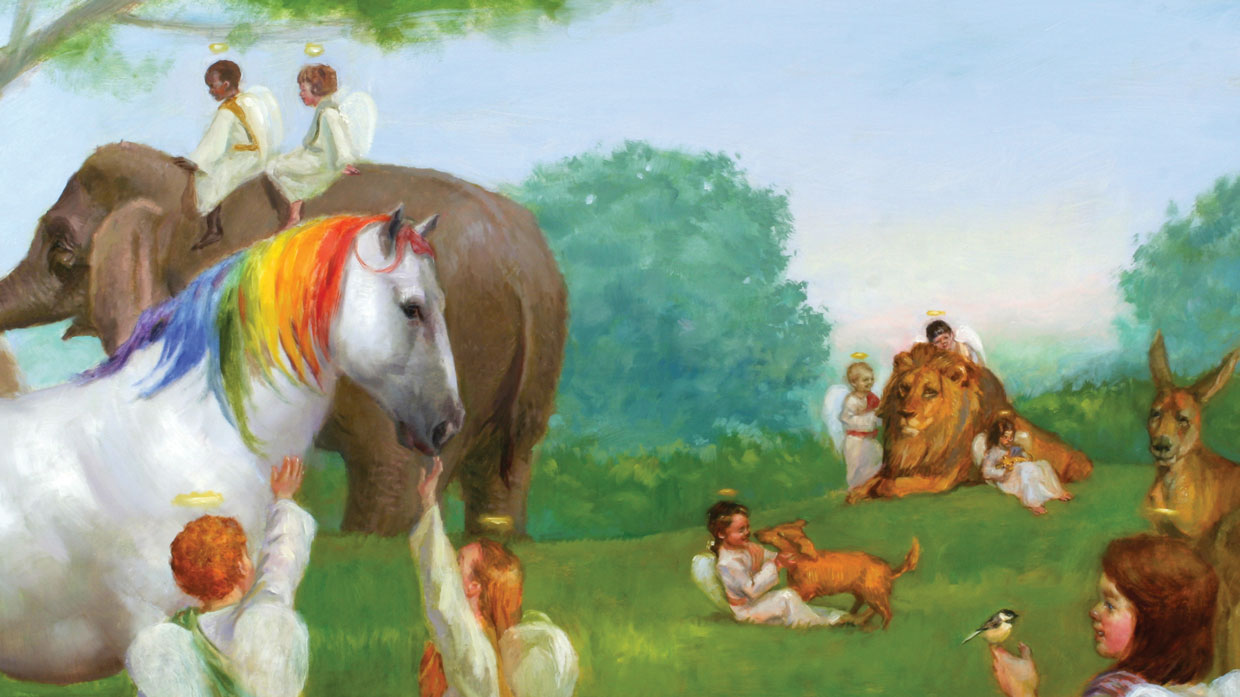

Much of what Colton describes contains better theology than I've heard in many sermons. His vision of heaven is unashamedly Trinitarian—the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are personal and present. Jesus' human, corporeal body still bears the marks of his crucifixion. (Colton doesn't know how to describe wounds, so he calls them "red markers," pointing to both hands and the top of each foot.) In his overwhelming love, the Father adopts children who died in utero.

But Colton also relates some details that made me scratch my head: Angels have swords to keep Satan out of heaven, men will fight flesh-and-blood monsters in the battle of Armageddon while women and children look on, and the Holy Spirit is "kind of blue."

The truth is we don't even know how much of Colton's experience we're actually dealing with. Many of his revelations are exposed during question-and-answer sessions with his parents over a period of two years. His dad interprets his responses and writes about them in the book. A coauthor adds perspective. Factor in the publishers, editors, film director, and producers, and by the time the movie rolls on the screen, we're so far removed from the horse's mouth that we aren't even in the stable anymore.

Much of the Heaven Is for Real conversation has focused on picking at every nuance of Colton's story, in attempts either to construct an accurate blueprint of heaven or to discredit his experience. The first group sees Colton's trip as an objectively repeatable event: If I die, then I will experience the same things Colton did. His story is morphed into an empirical apologetic for the afterlife. How frustrating it is that, upon returning, he didn't immediately pull out a box of crayons and catalogue everything he saw, that he didn't create a more comprehensive heavenly field guide.

The second group is composed mostly of Christian leaders who question, with one eyebrow raised, the legitimacy of Colton's report. Some take issue with the Westernized character of what Colton saw—Jesus wears a white robe and purple sash, he has brown hair and blue-green eyes, and heaven is physically above earth. Others align Colton's description of heaven alongside those in Scripture, like two DNA profiles, to point out the discrepancies. But most skeptics are concerned with the prioritization of Colton's experience over the authority of Scripture. To be sure, this is a legitimate problem.

The book certainly has been marketed this way. The title itself implies that the ultimate value of Colton's experience is to confirm heaven's existence from an eyewitness report. Finally, readers may think, a description of heaven we can trust! Four-year-olds have no agenda; they're blank slates. Colton's story is so reliable, so relatable.

Colton's grandmother reflects this attitude: "I accepted the idea of heaven before, but now I visualize it. Before, I'd heard, but now I know that someday I'm going to see."

Critics have jumped on these types of responses, eager to stamp out embers that have already burst into flames. Most turn to Jesus' parable of the rich man and Lazarus (Luke 16:19–31). Father Abraham refuses to send Lazarus back to warn the rich man's family of the pain that sinners endure in the afterlife. Why? Abraham says, "They have Moses and the Prophets; let them listen to them." If someone rejects Scripture's claims of heaven and hell, a messenger from the dead won't (and shouldn't) inspire faith. Certain writers have interpreted this to mean that because experiences like Colton's have the potential to supersede the authority of Scripture, they are worthless—possibly even demonic.

But is that fair? As history shows, ecstatic experiences are remarkably common in the church. They've been around since the church's birth, and they aren't likely to stop anytime soon. If for this reason we must toss Colton's story into the fire, we must also chuck in the ecstatic visions of the martyrs, the mystics, and any experience that might supersede "Moses and the Prophets."

So what should we do with Colton's story? Is his experience utterly worthless? Perhaps as an objective field guide to heaven. But many Christians have been too quick to throw the four-year-old kid out with the bathwater.

A Supplement to Scripture

The Bible presupposes the supernatural—and, as Christians, we're supernaturalists. We don't have the luxury of rejecting inexplicable experiences outright just because they're being mishandled by some.

Certainly, experience cannot serve as an ultimate guide, but it is valuable as a supplemental authority under Scripture. In Satisfy Your Soul, theologian Bruce Demarest adjusts our typical response to claims of supernatural ecstasies:

Experience is not the means by which finite man reaches upward to lay hold of God. On the contrary, experience is an important avenue by which God reaches down to touch us. Virtually everything we know about God has come through believing other people's experiences—from Moses, David, and Isaiah to Paul and John. Our experiences must be checked against Scripture, but the Christian's experience of God is not as problematic as some allege.

When my wife and I lived in Denver, we frequently snow-shoed in Rocky Mountain National Park. On occasion we'd come across a frozen lake. I was always quicker than she was to trot out onto the snow-covered ice—perhaps foolishly so.

Suppose we were given a map, outlining safe paths, warning of danger spots, and detailing the exact thickness of the ice across the lake. Our faith in the map would push us to test the ice, to traverse the lake, and it would guide our hike. With each step, our faith in the map would be rewarded. We'd slowly learn that the ice could support our weight so long as we followed the map's directions. The feeling of solid ice under our feet would gradually build our confidence in the map.

But what would happen if our confidence became misplaced? What if, after a number of safe steps, we became over-reliant on our own feet, tossed the map into the wind, and set out on our own? Most likely, we'd fall through the ice into a cold, watery grave.

Experience is a double-edged sword. If it stays in a supportive role, it actually fosters faith in Scripture. But if experience gets too big for its britches and supplants trust in Scripture, we're sure to lose our way, like hikers trusting our own feet more than a map.

In Surprised by Joy, C. S. Lewis writes,

What I like about experience is that it is such an honest thing. You may take any number of wrong turnings; but keep your eyes open and you will not be allowed to go very far before the warning signs appear. You may have deceived yourself, but experience is not trying to deceive you. The universe rings true wherever you fairly test it.

The experience of stepping out onto the ice isn't inherently destructive; it's necessary. Trouble comes, however, when we trust our experiences to support the weight of our faith. That's what so many have done with Colton's experience. Todd Burpo goes to great lengths to show how each piece of his son's vision recalls some portion of Scripture. But at the end of the day, the book is being marketed as a new, better map.

Rightly Discerning the Ecstatic

It's clear to see how Colton's experience has been abused and exploited. But how might it be handled positively, supportively? A brief survey of Christian mysticism shows us that ecstatic experiences are valuable, not because of the precise, objective details they reveal, but because they are subjective and personal.

It's true that many mystics intentionally sought ecstatic visions (unlike Colton or biblical figures) and in some cases downplayed the role of the church. But theologian Donald Bloesch observes that Protestants have been "too quick to deny [Christian mysticism's] universally true and abiding insights." A cautious reflection on the way some mystics understood their ecstatic experiences can help us rightfully discern those we encounter today, like Colton's.

In 1224, Francis of Assisi witnessed a figure descending from heaven. This figure appeared to be a man but also a six-winged Seraph. He was affixed to a cross with two wings extended over his head, two covering his body, and two stretched out in flight. As Francis observed the figure's radiant face, the figure smiled down at the monk. Francis was both overjoyed by the figure's beauty and grieved by his suffering on the cross.

Do you think Francis pondered over the type of wood the cross was made of? Do you think he analyzed the ethnicity of the glorious figure? No, Francis understood his ecstatic experience to mean he would be made like the crucified Christ in mind and heart. The vision left him with a renewed commitment to and love of Christ.

Three centuries later, Teresa of Avila had recurring visions for two and a half years of the risen Lord in his tomb, alive and glorified. Yet she admitted in her autobiography,

although I was extremely desirous to behold the color of his eyes, or the form of them, so that I might be able to describe them, yet I never attained to the sight of them, and I could do nothing for that end; on the contrary, I lost the vision altogether.

She concluded that the visions were meant for her personal contemplation, not to be studied like a textbook. She often found herself lost in the overwhelming sense of majesty caused by these visions and in response declared, "Thou art the Lord of the whole world, and of heaven, and of a thousand other and innumerable worlds and heavens, the creation of which is possible to Thee!"

Obviously, these mystical visions are quite unlike Colton's. But they show that the value of ecstatic experience isn't exhausted by objective analysis. The first time Colton mentions his experience, he simply says, "Dad, Jesus had the angels sing to me because I was so scared. They made me feel better." Years later, Todd Burpo described to his congregation the personal value of Colton's "trip" to heaven:

In my sermon that morning, I talked about my own anger and lack of faith, about the stormy moments I spent in that little room in the hospital, raging against God, and about how God came back to me, through my son, saying, "Here I am."

Heaven Is for Real is more than just a field guide to the marvels of heaven. It's the story of how God comforted a frightened child. It's the story of God's faithfulness to a grieving father.

What exactly happened to Colton Burpo—whether he actually experienced the glory of heaven or had a mere hallucination—will remain a mystery. But we live in a mysterious world, and we shouldn't be surprised when we encounter the miraculous and the supernatural. We should approach tales like this with critical discernment. We can't immediately accept them, but neither should we reject them haphazardly. We should test them under the light of Scripture, and we should celebrate the fact that God, who reveals himself through his Word, is faithfully active in our world, meeting us in ways that can't (and sometimes shouldn't) be explained.

Kyle Rohane is editor at LeaderTreks. You can follow him on Twitter @kmrohane.