When she graduatedfrom Bethel University in St. Paul, Minnesota, Karen Johnson believed God had called her to Japan. Two years later, Johnson still lives in Minnesota, working multiple jobs as she strives to pay off $43,000 in student loans.

"I needed this degree to be able to do [missions work]," said Johnson, who majored in biblical and theological studies and youth ministry. "But my degree has held me back."

credit Test

credit TestBecause of binds like Johnson's, colleges, universities, and other programs have begun initiatives to make sure student debt is not a barrier to missions work. Liberty University in Lynchburg, Virginia, for example, will soon put millions of dollars toward forgiving student loans for missionaries.

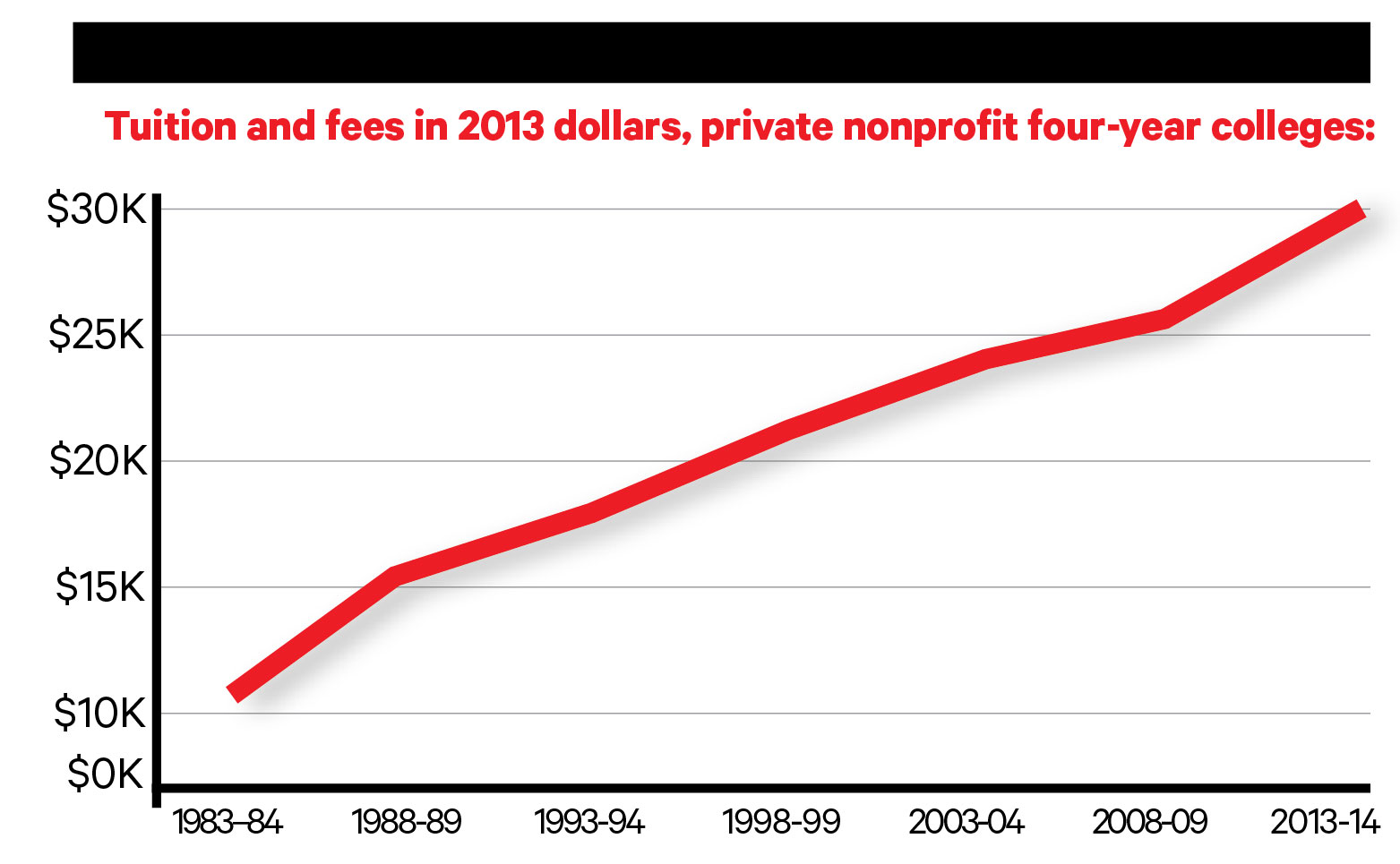

Many schools are starting or enhancing loan repayment programs "because the landscape has changed dramatically," said Luke Womack, founder and executive director of the GO Fund. Launched in 2012, the nonprofit helps graduates of any school, requiring only that they minister to unreached people groups. "The rate of tuition continues to skyrocket each year," he noted.

In the three decades since 1983, average tuition and fees at private four-year institutions rose by 153 percent, according to the College Board. And according to the Project on Student Debt, seven in ten 2012 college graduates had student loans, with an average debt of $29,400.

"What [mission agencies] told us over and over is that the number-one barrier to getting people to live and work overseas was debt," said Johnnie Moore, senior vice president for communications at Liberty. "They called it the black hole."

Liberty's program launches in May 2014 and has no cap on funding or recipients. Money comes from Liberty reserves and is open to any graduate serving overseas. Those accepted receive up to $30,000 per individual, with 20 percent of the total debt paid each year. More than 60 people have inquired about the program.

Messiah College in Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania, also launched a debt-forgiveness program, in early 2013. Two missionaries are enrolled, one in Jordan and the other in Kenya.

Messiah's program came about when a donor made a "significant gift," said Jon Stuckey, director of development. The school wants to grow the endowment. "Our goal is [to] make sure anyone who truly feels called to the mission field can follow that call of God on their heart without worrying about the student debt they may have incurred," said Stuckey.

Wheaton College in Wheaton, Illinois, already has a debt-forgiveness program, which has supported missionaries in Mexico, Mozambique, East Asia, and Thailand, among other locations.

Many mission agencies will not accept graduates with significant debt. The International Mission Board requires personnel to have less than $1,500 in unsecured debt; New Tribes Mission asks candidates to be free from debt, but considers individual circumstances; and SEND International requires candidates to be working to pay off debt.

San Diego Christian College offers a loan-forgiveness program for missionary pilots. Two organizations, MedSend and the Southwestern Medical Clinic Foundation, do so for medical missionaries from any institution.

While she strives to pay off her debt, Johnson has applied to the GO Fund. When she is debt free—which may take six more years—she plans to go to Tokyo with SEND.

For administrators at Liberty, the motive is compelling: "We believe this is the first generation that can see the completion of the Great Commission," Moore said. "We're entirely convinced of it."