Support Reform

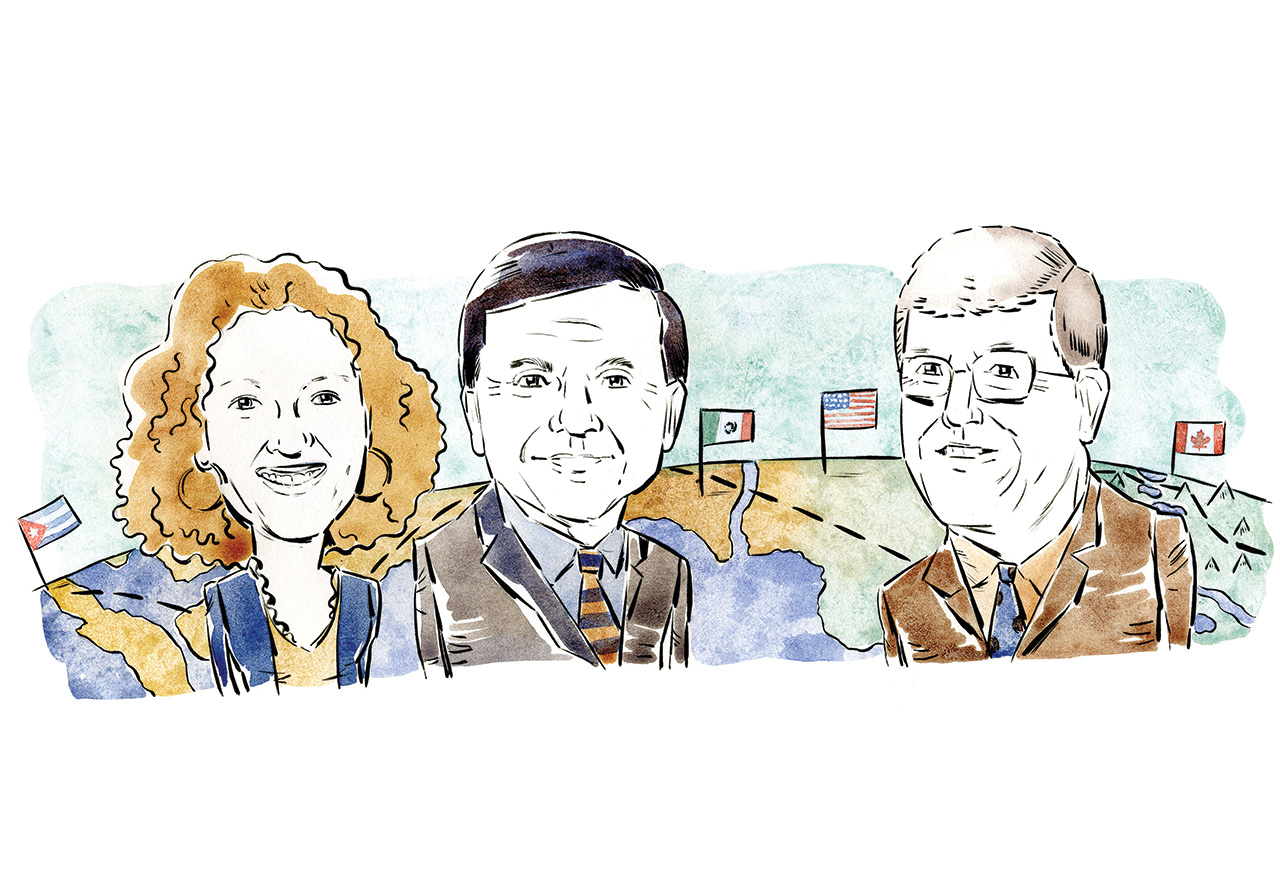

Kedri Metzger is senior attorney with Religious Worker Immigrant Legal Services of World Relief, based in Baltimore.

Immigrants are strengthening the church and revitalizing some denominations with significant growth. Many of these churches are started by local leaders who emphasize evangelism and know the culture and language of the growing immigrant population in the United States. But some of these pastors lack valid immigration status and face a complex and painful dilemma.

Alex and his family crossed the border illegally when he was an infant. Years later, after becoming a Christian, he began a ministry in his community that has grown into two separate church sites. Alex serves as a volunteer, unable to work since he does not have the necessary immigration papers. He has a family, including a child with Down syndrome who is a U.S. citizen. This complicates his situation even more: If Alex leaves the States, his child would lose access to crucial medical care. Alex has considered bringing himself to the attention of immigration authorities to plead his case before an immigration judge. But this would risk for being deported away from his child, to a country he doesn't remember.

Like Alex, some pastors came to the United States as small children. Some intentionally crossed the border undetected, while others entered on valid visas and later lost their immigration status through technical mistakes made by themselves or church leaders. Under current law, there are no remedies for these mistakes.

Those without valid immigration status are required to complete the immigration process abroad. If a pastor leaves the country to do so, he will likely face a 10-year bar from applying for reentry. This leaves pastors stuck: unable to correct their status from inside the United States, and barred from reentering if they leave.

How should a church denomination respond? The first step is to locate competent immigration legal advice. It cannot be left to ethnic ministry directors, church planters, pastors, and other church leaders to advise these individuals on their immigration legal status.

If the church helps, are they violating the law? Church leaders often worry that they are not submitting to authorities by allowing pastors or other volunteers to participate in church life. But the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) does not require church leaders or members to report pastors who are here illegally. Currently, the ina says churches cannot employ individuals who do not have permission to work inside the United States.

Churches and denominations have a great deal of freedom to develop policy and practice. We must challenge ourselves to pursue the facts and understand the biblical perspective. The church should seek to balance care for our brothers and sisters with their responsibility under the law. We must wrestle with our commitment to the mission of the gospel and consider the kingdom purposes of these "fishers of men" in our midst.

Teach Compliance

Mark Tooley, president of the Institute on Religion and Democracy, is author of Taking Back the United Methodist Church.

Churches are called to minister to all persons to whom they have access. This includes persons who are in this country illegally. Outreach includes gospel proclamation, inviting others into the life of the church, and charity when needed.

When it comes to illegal immigration, the church should teach compliance with the existing law, even to those who are pastors and ministry leaders with significant responsibility. Such counsel may include helping illegal immigrants seek legal status. Or it may mean suggesting a vocation that requires returning home, where the need of service may be greater. The church also needs to reach immigrants from non-Christian backgrounds, which is more challenging but probably more important.

As Hispanic immigration continues to slow, churches will need to get better at reaching immigrants from other cultures. After Mexico, Asia is the largest source of new immigrants. Churches will also have to be open to learning from immigrant missionaries and pastors who are here legally, and who are likely more effective in this demographic than most American congregations.

Most traditional forms of American Protestant worship are not appealing to immigrants. Global South Christianity is overwhelmingly charismatic and/or Pentecostal. Many vibrant, growing immigrant congregations in America are too. Traditional Protestant and evangelical congregations, if they want to attract immigrants, may have to adjust their worship style or create new worship opportunities that appeal to immigrants and immigrant pastors in both form and language. Liberal congregations that are the most politically outspoken about justice for illegal immigrants preach a social gospel that is not appealing to most immigrants.

Effective ministry to immigrants also precludes romanticizing their experience. They are simply people and fellow sinners, exemplifying a full range of vices and virtues, as all peoples do.

Breaking the civil law is a sin according to every major Christian tradition. Even as churches prioritize gospel outreach, they must remind immigrant pastors who are not legal residents that as Christian disciples they need to resolve their legal status.

To acclaim them as victims meriting redress is dishonest and points them away from the obedience, service, and self-denial that are central to following Jesus. Some individuals may follow conscience by returning to their homeland. Churches should help equip them for ministry and economic survival if they do.

As for pastors who lawfully seek to remain, churches should offer appropriate counsel, including reminding them of their civil obligations in a new land. What does it mean to be Christian in America today? A century ago, churches taught immigrants how to become American. Today churches need to teach immigrants and natives how to witness and prevail in a secular culture increasingly hostile to the gospel.

Uphold Their Ministry

Mathew Staver is chairman of Liberty Counsel and board member and chief legal counsel of the National Hispanic Christian Leadership Conference.

Around the world, millions are leaving their home countries and migrating to new lands. Many are Christians or come to faith after arriving in their new home, and they are planting churches and doing ministry among their own people.

This global phenomenon has spawned the pioneer field of diaspora missiology, which appreciates these communities as potential partners in the worldwide mission of the church.

In the United States, immigrant churches—a significant percentage of which include members who are not legal residents—are revitalizing Protestant denominations and the Catholic Church. It is now no longer a question of whether churches and seminaries should be engaged with immigrant churches, but rather how to meet the daunting ministry challenges that they present.

We are witnessing all sorts of educational programs spring up. They are designed to equip lay leaders and pastors. Numerous projects target the personal and family needs of immigrants, which include food and clothing, basic medical care, after-school tutoring, English classes, and legal advice. Education and compassion are the order of the day.

It is not surprising that many denominations and the National Association of Evangelicals have passed resolutions favoring comprehensive immigration reform. Some criticize these measures, convinced that respect for immigration law should be the criterion for dealing with such Christians and their pastors. Anyone conversant with that legislation would recognize that nothing that has been mentioned is illegal. Church bodies can do a lot within the limits of the law. A pastor's immigration status remains within the purview of federal authorities.

The situation for seminaries is different than for church bodies. Some seminaries fear losing federal funding for scholarships if these pastors enroll in their academic programs. Others worry about the loss of donations from conservative constituencies.

Seminaries that desire to serve the immigrant community have developed several avenues for training leaders who do not have valid legal residence. Some offer nondegree tracks at a level commensurate with the educational background of many of these pastors. Others simply do not ask students about their status, mirroring many institutions of higher learning. It is understood that they cannot qualify for certain scholarships. Several states now grant access to university programs and tuition benefits to students who do not have legal residence. Seminaries are trying to figure out how to fit into this educational landscape.

Changes to immigration laws are on the horizon. Are churches prepared to help immigrant pastors solve any problems with their legal status once reform comes? Will seminaries be willing to invest financially in this low-income group? To prepare and support these pastors within an outdated and unworkable immigration system is complicated. Coming days will yield other challenges. But one thing is for sure: These pastors will be important coworkers in the future of the church.