Despite what you may have heard, the "man of steel" is no Son of Man.

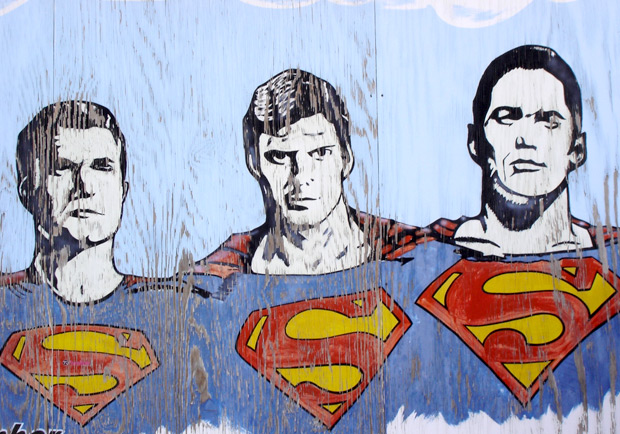

With every new Superman movie, this rumor that fans look to him as the savior of humanity spreads through trailers and interviews. The directors of the last two Superman flicks found religious symbolism particularly attractive, layering on clunky monologues and heavy-handed parallels between Superman, born as Kal, the "only son" of the House of El, who was "sent to Earth to save it," and Jesus Christ, the only son of God, who was sent to save humanity.

"He's a Christlike figure. There's no two ways about it." Zack Snyder, director of the new Man of Steel, confirmed to the Los Angeles Times.

I disagree. Even as a comic hero-loving Christian, I don't see Superman as a savior. The greatest superhero of all time? Absolutely. An enduring character I'm happy to watch again and again? Yes. But it doesn't take an act of God to make a superhero worthwhile. Superman represents different things to different people; to me, he's the ultimate volunteer, using his unique talents for others out of a Midwestern sense of "pitching in" on a large scale.

Even with a complex, longstanding hero like Superman, it's no accident that the Christian imagery comes up so often, from Entertainment Weekly to Fox News. Man of Steel is the latest blockbuster to get the Christian-marketing treatment, wrote RNS blogger Jonathan Merritt.

"Warner Brothers, the studio behind the film that grossed more than $125 million this weekend, hired faith-based public relations firm Grace Hill Media to make sure the Christian market didn't miss the connections," he said.

How could we miss them? Richard Corliss of Time Magazine breaks down the (many) explicit parallels drawn between Kal-El and Jesus:

Man of Steel takes its cue from Bryan Singer's 2006 Superman Returns, which posited our hero as the Christian God come to Earth to save humankind: Jesus Christ Superman. Goyer goes further, giving the character a backstory reminiscent of the Gospels: the all-seeing father from afar (plus a mother); the Earth parents; an important portent at age 12 (Jesus talks with the temple elders; Kal-El saves children in a bus crash); the ascetic wandering in his early maturity (40 days in the desert for Jesus; a dozen years in odd jobs for Kal-El); his public life, in which he performs a series of miracles; and then, at age 33, the ultimate test of his divinity and humanity. "The fate of your planet rests in your hands," says the holy-ghostly Jor-El to his only begotten son, who goes off to face down Zod the anti-God in a Calvary stampede.

Those are the coherent allusions, but in the imagery-obsessed, religiously illiterate Hollywood, many others become nonsensical. The adopted Clark Kent was raised in a God-fearing home in Man of Steel, and asks of his alien powers: "Did God do this to me?" But when the full-grown Clark seeks advice in a church, a scene rife with Garden of Gethsemane imagery, a priest tells him to take "a leap of faith"…faith in humanity, that is.

All this God-comparison stuff just makes the larger-than-life Superman more distant and handicaps the romance in Man of Steel. It doesn't bring him down to earth, and it doesn't help audiences understand the real Messiah. No matter how much religious imagery gets used or how many parallels are infused into the plot, comic heroes lack the very thing that make Jesus our Savior. They can save lives, but they can't save souls.

Jor-El tells his superpowered son to be humanity's "ideal to strive toward," but ultimately the only ideal this Superman represents is hope…not in a specific promise, just hope itself. He also doesn't have anywhere to save humanity to, no "better place" to offer them, seeing as (Superman origin spoiler…) his home planet Krypton is destroyed. As a hero, he can inspire us to try harder and aim higher, but even Superman has limits.

Synder, the Man of Steel director, can insist all the Christ-like parallels are "the tried-and-true Superman metaphor," but it's not so clearcut. The argument can be made that Superman's origin story draws from the "messiah mythos," but so do the evergreen "chosen one" hero arcs of hundreds of other examples of fiction.

Many superheroes, and Superman in particular, represent the aspirational aspect of human nature. That's the whole point of the story. In an indifferent world, Superman's creators Joe Shuster and Jerry Siegel dreamed up a man with both the will and the ability to withstand the seemingly insurmountable evils of their time, such as Adolph Hitler. The caped-hero's creation came as physical wish-fulfillment to confront a very physical problem.

We continue to look for heroes in pop culture to address our current problems. The New York Times knocked Iron Man 3 for failing to adequately depict modern terror, and Man of Steel only ventured into today's real world during a brief discussion of a surveillance drone. Still, it's not these heroes' cutting-edge understanding of the horrors of our time that makes them popular and powerful; it's their willingness to fight evil in all circumstances, usually for the sole motivation of fighting evil. As CT's review wrote, "Superman… is there mostly to satiate that part of the American psyche that wants their messiahs to punch things, too." Fighting evil is a worthy ideal, but a very human example.

I don't dispute the idea that the Superman archetype relies on Christ-like characteristics; the popularity of this form demonstrates how much we as humans are drawn to the attributes of our Savior. But, Kal-El is not humanity's Savior and falls far short of Christ. Christ represents a very specific hope and an eternal promise much better than just a longer lifespan. Next to that kind of power, sacrifice, and deliverance for all, Superman seems downright puny. So let Jesus be Christ, Hollywood, and Superman be a hero.