Last November, the Church of England shocked many watching Christians by voting against allowing female bishops. Justin Welby, the newly named Archbishop of Canterbury, declared it a "very grim day," while Rowan Williams warned that the Church had "lost a measure of credibility," acting "willfully blind to some of the trends and priorities of that wider society."

Christians across the theological spectrum threw in their opinions, which ranged from perplexed to near despair. Idaho pastor Douglas Wilson, a staunch complementarian, nonetheless confessed that he didn't understand the logic of "affirming the ordination of women priests and opposing them as bishops." Former dean of Duke Chapel Sam Wells, meanwhile, said that when he heard about the vote, he "sat down and wept. I hadn't allowed myself to imagine that this could happen."

The decision prompted much discussion outside the church as well. Most secular voices accused the church of sexism. British prime minister David Cameron said the church's leadership had to get with the times, "to be a modern church, in touch with society, as it is today, and this was a key step they needed to take." Viewing the matter as one of civil rights, some have questioned whether the church is denying these women theirs—namely, the right to assume positions of authority based on skill and not gender.

In the West, where civil liberty is a core value, it is indeed appropriate to consider whether women's ordination is a right. Appropriate, and complex. Whenever Christians draw on the language of rights, particularly as it pertains to the church body, we wade into murky territory.

On the one hand, Christians are to advocate for the marginalized and downtrodden, and the church championed civil rights movements that improved the status of women and minorities in our country and elsewhere. These are good, Scripture-mandated works.

But within the context of the church, in contrast with broader society, can Christians really claim a "right" to anything—especially to positions of calling and authority?

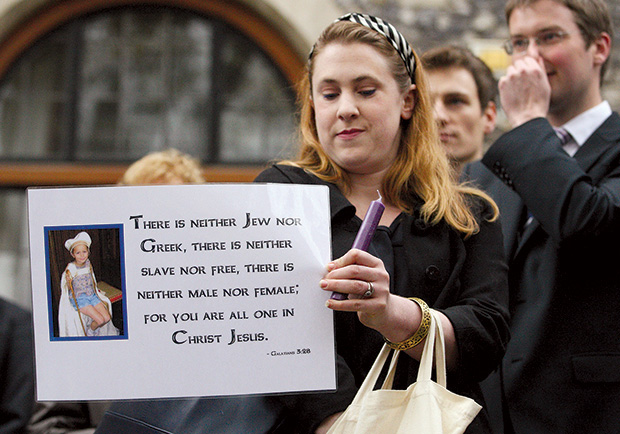

As the Church of England controversy demonstrates, some Christians would answer this question with a resounding "yes." In a similar fray within the Catholic Church, one woman arguing for ordination compared the fight to the civil rights movement: "We're the Rosa Parks of the Catholic Church."

But there is good reason to be concerned about the philosophical underpinnings of "rights" language. For one, most rights language is pervasively individualistic. Stanley Hauerwas notes in his essay "Memory, Community, and the Reasons for Living: Reflections on Suicide and Euthanasia" that

Rights language suggests we should be able to determine our lives … and what we shall do with [them]. But it is fundamental to the Christian manner that our lives are formed in terms not of what we will do with them, but of what God will do with our lives, both in our living and our dying.

Hauerwas grounds this conclusion in two central Christian doctrines: We are created beings, and we are ransomed individuals who were "bought at a price" (1 Cor. 6:20). As Christians, we acknowledge God's claim on our lives as the One who created us for a purpose. We also acknowledge that in Christ, our lives are not our own (1 Cor. 6:19). Through sin we became indebted to him, so the economy of God is not one of rights but of grace. God provides out of his divine, gracious character, not because of any rights inherently owed to us.

Within the context of the church, can Christians really claim a 'right' to anything—especially to honored positions of calling and authority?

This divine economy should guide the church as we face the ethical, and ecclesial, issues of the day. It's true that many Christian ideals—fairness, justice, dignity, to name a few—overlap with those pursued by rights activists. But the means are quite often different. Rights language is humanistic in tone, placing the locus of authority with the individual rather than with God or his church. When Christians put forth arguments ultimately based on human rights, they are making a costly theological statement, one that subtly supplants God as our true and ultimate head.

All this helps us grapple with women's ordination, whatever our convictions, in a truly Christian way. Theologians such as N. T. Wright have advocated for women's ordination by appealing to scriptural witness. As the debate continues within the Church of England and many other church bodies, his is an example to follow. On a subject fraught with strong opinions and high emotions, our language needs to be precise, biblical, and theologically nuanced. To this end, we have a rich vocabulary to draw on: the language of the love and salvation of God.

Sharon Hodde Miller, a Ph.D. candidate at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, contributes to Her.meneutics (ChristianityToday.com/women) and writes at SheWorships.com.