The babies come in all sizes.

They arrive at the rescue center weighing anywhere from 1.5 to 36 pounds. Some are new-borns, some are 19 years old. Technically, then, they aren't all babies. But technicalities weigh little in matters of life and death. All the children brought here are helpless and need critical care—or they will die. Of the 1,200 children treated at the center last year, 85 did die.

I have traveled here with World Help, a faith-based humanitarian group located near my home in Virginia. World Help partners with ministries worldwide, bringing to impoverished communities a bit of America's bounty. One of World Help's more than 100 partners is Hope of Life here in Zacapa, a flat, fertile valley nestled next to the Rio Grande de Zacapa in eastern Guatemala.

Rescuing babies has brought me here.

The fragile, dying babies that surround me remind me of other babies I tried to rescue, years ago, in America, at the crisis pregnancy center. And at the abortion clinics. And even the ones I could not bear. I could not see or hear or hold those babies. But these I can. And I do.

Crossing to Hope

The ministry began in 1987, when Carlos Vargas made a sickbed bargain with God.

Born and raised in the Guatemalan village of Llano Verde, as a teenager Vargas left for the United States, where he became a successful businessman. But he was forced to return to Llano Verde when an unknown illness crippled him, threatening to keep him in the village the rest of his life. Moved one day by an elderly beggar, Vargas gave the man money and promised God that if he could get out of bed, he would spend his life serving the poor.

Both God and Vargas kept their word. Vargas recovered, and he soon built a home for the elderly. It became one of the first buildings of a ministry that has burgeoned into a 3,000-acre campus—almost 5 square miles—that serves Guatemala's most vulnerable citizens from crib to wheelchair. Beyond home base, Hope of Life serves outlying communities by sponsoring children, building wells and new homes, running feeding centers, leading schools, and more. Partnering with World Help, American companies provide surplus goods in a makeshift store where villagers shop using tickets given by Hope of Life based on family size. Missions teams—which descend upon the campus every week—distribute new shoes to surrounding villages. The ambulance used to transport rescued children was donated by a church in Virginia.

Operation Baby Rescue, a partner program with World Help, is only the beginning of Hope of Life's ministry. "While rescuing babies is a priority, we are investing in the rest of their lives and in their communities," explains Noel Yeatts, vice president of World Help. "It doesn't end with baby rescue. We are doing multiple things to break the cycle of death and despair."

Today, one of the rescued "babies" who just arrived is 13-year-old Noë, who rests in his father's arms. They are accompanied by six more sick children and five family members—each toting a few possessions in small plastic bags. They have walked for hours from a remote mountain village, arriving at the bank of El Motagua River. They are met by World Help and Hope of Life staff. Rugged oarsmen ferry them to the other side, where an ambulance awaits.

Noë's father bears his son up the steep grassy bank toward the ambulance. His dark face is set grimly, his eyes lit with fear. Many indigenous Maya mountain dwellers suspect Western Christians of wanting to trade the children in the country's thriving human trafficking scene—or worse. Some families, believing shamans' promises to heal their sick children, have only seen their loved ones deteriorate. Between fear and empty promises, Noë suffers— from cerebral palsy, pneumonia, and severe malnutrition. His father finally lifts his son's limp-limbed body into the ambulance. Medical personnel lay Noë gently on a bench next to me, as I take into my own arms Rosalia, another child who has crossed the river today.

I loosen Rosalia's swaddling blankets in the sweltering heat of the ambulance. Rosalia's limbs, like sticks, betray her malnourishment. It is immediately clear that she has Down syndrome. She is wearing only pink eyelet underpants; white scabies adorn the rest of her thin body. She seems not to notice the siren scream or the jolts as we drive along the rocky road carved into a wooded thicket leading away from the deadly river toward life.

Yet if I speak softly to her, she turns her unfocused eyes toward my face. When I learn through a translator that tiny Rosalia is 4 years old, the lightness of her being becomes unbearable in my arms.

At the rescue center, I learn that Rosalia weighs 14.8 pounds. Noë, a teenager, weighs 46.

During my stay at Hope of Life, the center receives 17 sick and dying children. Their ailments range from brittle bones to hydrocephalus. Most are malnourished. Before I leave, one of them will be borne by his lightness to the grave.

Love in Action

Rosalia, Noë, and the five other children brought across the river this afternoon are joining 30-some children in the rescue center. Among these are Diego, a few months old. He is now a chubby, happy baby, a new development in his short life: When he was a few days old, Diego was discovered in a heap at the trash dump while dogs fought over his umbilical cord.

Jenri, age 2, was brought into the center some weeks ago. He weighs 10 pounds, two more than when he arrived. At 49 pounds, Yolanda, 13, is a wisp of a girl. Deaf and mute, she is slow to smile but has started to shyly practice her newly learned sign language with visitors.

Fortunately for Yolanda, Hope of Life opened a center for special-needs children right next to the Baby Rescue Center this summer. A World Help board member whose daughter recently died of cancer donated the money to build the center. When Yolanda's condition stabilizes, the center will become her permanent home. Other children brought to the center will, when they are well, return to their families. Many family members stay in temporary homes near the rescue center while their children are treated. Children who are here due to abandonment, neglect, or abuse will live at the ministry's orphanage. A 500-student K—12 school on the campus serves all of the orphans for free. About half of the students come from wealthy families able to pay tuition.

This has two benefits: The school supports itself, and the daily socialization of rich and poor children helps close the social gap that's a defining characteristic of Guatemala, a country rated as one of the worst for income inequality.

Hope of Life sustains its home site with income from its greenhouses and a tilapia farm, which produces over one million pounds of fish annually that's sold in local markets. The bustling campus employs about 400 people, a significant contribution in a country with staggering poverty (see "Hungry Guatemala"). But this is a fraction of the efforts of Hope of Life. In fact, Vargas says, 90 percent of its labor and budget are expended outside the home base through projects like Total Village Transformation, which gives communities a well, a church, and a school.

"When we say 'God loves you,' " says Sal Vargas, who helps his brother run Hope of Life, "it's not just words—it's love in action."

One of the children carried across the river has died. Nelson was 19 months old, the child of a young mother who traveled down from the mountain and crossed the river with him. She had come wearing a lilac shawl over a colorful cotton dress—Sunday best for a somber day. After Nelson arrived, the effects of his malnutrition worsened, and staff decided to send him to the hospital an hour away. He died on the way.

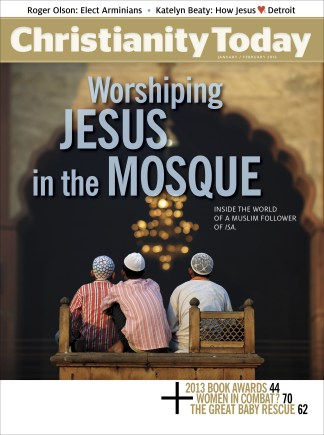

When I learn through a translator that tiny Rosalia (above) is 4 years old and 14.8 pounds, the lightness of her being becomes unbearable in my arms.

Today we are holding a small service for him outside the center. A miniature casket covered in silky white cloth sits open atop a table surrounded by vases of plastic flowers. Yeatts offers a short message of comfort to the gently weeping mother and the handful assembled. Vargas translates for Yeatts into Spanish, and a center volunteer translates it to the mother's Mayan dialect. Nelson was her only child. His father, like many villagers, did not want his son taken to the rescue center. His son's death will reinforce his fears, perhaps making it likely that others will delay getting help for their sick children until it is too late. In communities where word circulates with surprising reach and speed, Vargas must now try even harder to build trust.

The first children I meet at Hope of Life are Lady and Alicia. They are playing outside the orphanage with other children in the morning sunlight before school. Sisters ages 9 and 10, they have thick, shiny black hair and warm brown skin. But when they were brought to the rescue center five years ago from a remote village, their skin hung on their visible bones like sackcloth.

They had been abandoned by their mother and father in their grandmother's care. She tied them to a bed with ropes when she left them to earn money by washing clothes. Today, they glow with life and joy as they play with the other orphans. They attend school at Hope of Life, which will also cover the girls' college tuition should they choose to go.

Nelson may have had these opportunities, too, had he been rescued in time. Or perhaps if the hospital had been closer, as soon it will be. Built in partnership with World Help, Hope of Life is completing St. Luke's Hospital, rising six stories, topped by a helicopter pad, equipped to meet the needs of the children who come to the Baby Rescue Center, and others as well. Much of the medical equipment has been provided, in large part through a U.S. program that allows organizations like World Help to claim unused and unneeded military surplus. Once the hospital is open, children like Nelson will have an even greater hope for life.

These babies, those babies, all unbearably light. They are there, they are here. They exist, whether we see them or not, slender shafts of life eclipsed by the dark weight of the world.

I have never borne a baby of my own. Two-thirds of fertilized eggs—babies too light to bear—fail to implant, scientists surmise. My womb is a grave. My friend the biology professor once said to me, "When you get to heaven, you might find it filled with your babies." Perhaps. But I believe that Nelson will be there, along with many other children. Yet I know, too, that I don't have to wait to get to heaven to see all of my babies: They fill the earth. And they come in all sizes.

Editor's Note: At press time, World Help revised its 2011 reported revenue after discovering a major over-valuation of noncash donations (medicines), likely due to misrepresentations from a former consultant. Its 2010 and 2009 reports will also be revised. For more information, see worldhelp.net/nov2012_statement_revised_financials/.

Karen Swallow Prior is chair of the English and modern languages department at Liberty University. A writer for Her.meneutics and The Atlantic, she is the author most recently of Booked: Literature in the Soul of Me (T. S. Poetry Press).