By the sixth century, the church was wealthy and full of wealthy people. How did the rich get their loads through the eye of the needle into the kingdom of heaven? How, in other words, did an institution pledged to recognize the blessedness of the poor gradually reconcile itself to unprecedented wealth? Peter Brown's latest, very substantial, book, Through the Eye of a Needle: Wealth, the Fall of Rome, and the Making of Christianity in the West, 350-550 AD (Princeton University Press) gives a deliriously complicated answer.

Through the Eye of a Needle: Wealth, the Fall of Rome, and the Making of Christianity in the West, 350-550 AD

Princeton University Press

792 pages

$32.00

Brown follows the money from Rome to Milan, to North Africa, to Gaul. He takes the measure of superrich pagans like Symmachus, as well as Christian leaders who wrote about riches, like Ambrose, Augustine, Paulinus, Priscillian, Popes Damasus and Gelasius, Jerome, John Cassian, and Salvian. As usual, Brown leaves no stone unturned in his search for insight and evidence. He examines texts, of course, but he pays close attention to architecture and archeology and late Roman art. He paints a colorful social setting for early church debates about theology and ethics without becoming reductively sociological, and often overturns accepted mytho-history in the process. He quietly draws on contemporary theory but typically lets ancients speak for themselves because his aim is to introduce us to an exotic world. Through it all, he focuses the masses of details by treating attitudes, beliefs, and practices about wealth as a "stethoscope" to hear the heartbeat of late Roman and early Christian civilization. In a brief review, I can do more than hit some highlights.

A New Model of Pastoral Power

Wealth did not immediately inundate the church in the aftermath of Constantine's conversion. The "Age of the Camel" begins in the 370s, not the 310s. Through the central decades of the fourth century, rich Christians continued to spend their money much like their pagan counterparts. Wealthy believers were more likely to bestow their gifts on their city than on the church or the poor.

The transitional period between 370 and 430 was pocked with a series of debates on wealth. Paulinus of Nola set a standard of voluntary poverty. Jerome clashed with many people about many things, but the question of wealth recurred throughout his embattled life. Brown intriguingly examines the Pelagian controversy (over the doctrine of original sin and the role of free will in attaining righteousness) as a controversy about wealth. When the ceasefire finally came, Augustine had triumphed over Pelagian ideas of salvation and economics alike, the criminalization of riches and the rich. For Augustine, wealth was a means of expiation, alms and benefactions as the sump pump by which sinners clear the sewage that daily seeps into their souls.

According to Brown, the Roman way of life did not slip away into that good night; the empire went down raging. Yet barbarian attacks on Rome itself were devastating. Many saw fortunes accumulated over centuries carried away; other wealthy Romans fled to Carthage, where they tried to maintain their Roman ways but soon got embroiled in the Pelagian controversy.

As the older aristocracies collapsed in the West, new forms of churchly order and fresh configurations of power took shape and eventually displaced Roman models. Pastoral power represented a new kind of powerless power, power without swords or troops, and the bishops managed wealth that was understood as a trust for the poor, a wealth without wealth. By the end of the fifth century, the church was a wealthy institution in a world of scarcity, and the bishops had taken the place of wealthy landowners as the magnates of the countryside. The shift from a "plebeian" to an "aristocratic ideal of leadership" was hesitant and contested. It was the social shift behind debates about predestination, grace, and freedom that broke out among monks of Provence during the fifth century.

The Professional Poor

Brown is not merely interested in following the money. He is more interested in the transformation of imagination that accompanied, formed, and followed from the church's reconciliation with wealth. For Romans, wealth was for display, a way of radiating splendor: They were early practitioners of "conspicuous consumption." Ancient Romans also knew all about gift-giving. Aristocratic patrons maintained the loyalty of clients through gifts. Emperors gained the enthusiastic support of the people with bread and circuses. Local bigmen won lasting memory by donating buildings or games to the city. They gave to be given to in return, knitting the empire into what Cicero and Seneca saw as an intricate web of benefit and gratitude.

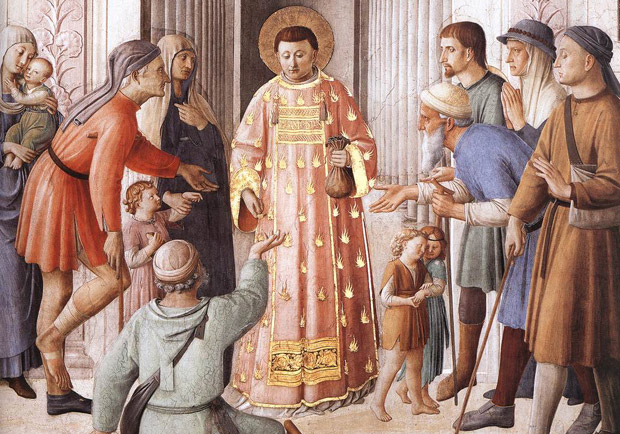

Christians too gave in order to receive. Yet over the centuries that Brown surveys there was a gradual but epochal shift in the imagination of giving. Christian giving was not competitive because Christians believed they gave up earthly wealth to gain a share in God's inexhaustible heavenly treasure. The treasury of reward was as infinite as God Himself. As Brown repeatedly and strikingly says, giving split the fixed boundary between heaven and earth; each small gift was a cosmic drama. Drawing on Jewish sources, Christians emphasized giving to the poor, who were re-imagined as brothers rather than distant others. In Christian giving, social lines were blurred as much as cosmic ones.

Monasteries provided the keys that opened heaven to the rich. By the end of the sixth century, "monks gradually came to eclipse the poor as the privileged others of the Christian imagination." As the professional poor, monks went through the needle's eye on behalf of everyone else. Gifts to monasteries were gifts to God's poor. Monasteries, further, operated on Augustine's theory concerning gifts and forgiveness. A medieval nobleman's bequest to a monastery was as self-interested as a Roman Senator's funding of games, but the nobleman reached beyond earthly glory. He hoped to store up treasures in heaven and cleanse his sins.

Brown's book is at its best in showing the slow transformation of Roman society into Christendom and in explaining how the story of wealth forms one of the main threads in the story of "Christianization." Under pressure from biblical sources, Christians reconceived poverty not as economic deprivation but as social and political vulnerability. In Scripture and eventually in the Christian imagination, the poor were those who seek justice. This definition of the Christian poor "did the most to secure the eventual triumph of Christianity in the cities in the course of the fifth century" because it implied that the church's response to poverty had to establish systematic justice rather than being satisfied with charitable relief. In his writings on wealth, Ambrose evaded systematic oppressions like the Roman tax system, but later Western thinkers concluded they could assist the poor only by aiming for a wider transformation of society. Christianization involved both a change in the external circumstances of the church and an internal transformation of the goals of Christianity itself, and the poor were crucial to that internal shift.

Pluses and Minuses

So the rich squeezed through. What should we make of that? On the plus side, Brown demonstrates that the medieval theory of giving took shape as the church became increasingly conscious of the biblical emphasis on justice for the poor. Late antique Christians were also right to acknowledge that Jesus does promise rewards to the generous. On the down side, the monks, with their vows of poverty, made wealth innocuous to everyone else. So long as the rich gave bequests to monasteries and churches, their wealth seemed unproblematic. The system removed the sting from the prophetic "Woe to the rich." And, the basic lineaments of the crass quid-pro-quo of late medieval indulgences become visible quite early, articulated by no less a figure than Augustine.

That Through the Eye of a Needle leaves the reader in a somewhat bewildered state of ambivalence is a sign that Brown has captured the rough texture of real history. It is testimony to the success of Brown's subtle, provocative, and beautifully written book.

Peter Leithart is pastor of Trinity Reformed Church in Moscow, Idaho. He is the author, most recently, of Between Babel and Beast: America and Empires in Biblical Perspective (Cascade Books).