Yesterday's article in CNN's belief blog, "My Take: When Evangelicals Were Pro-Choice," is the most recent attempt to relativize evangelical convictions about abortion. Author Jonathan Dudley argues that, "The reality is that what conservative Christians now say is the Bible's clear teaching on the matter was not a widespread interpretation until the late 20th century."

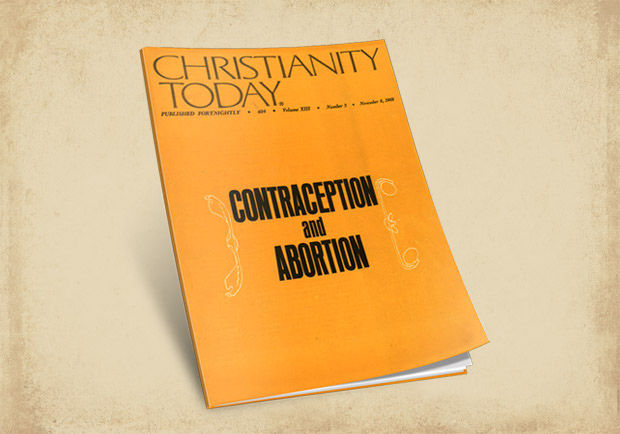

Dudley made the same point in his 2011 book Broken Words: Abuse of Science and Faith in American Politics. In the CNN piece, he notes a 1968 Christianity Today issue focused on contraception and abortion. In that issue, Bruce Waltke, at Dallas Theological Seminary at the time, Dudley says Waltke argued that "the fetus is not reckoned as a soul." Dudley also notes that the Southern Baptist Convention passed a resolution in 1971 affirming that abortion should be legal, to protect the life of the mother and her emotional life as well.

He's certainly right about the Southern Baptist Convention at the time. But he's mischaracterized Bruce Waltke's views. Waltke was writing about Old Testament views on contraception. The Old Testament does, in fact, seem to make a distinction between the life of a child and the life of a fetus (it never extracts a "fetus for a fetus" principle, for example). But as Waltke notes, the Old Testament nonetheless "protects the fetus," And "while the Old Testament does not equate the fetus with a living person, it places great value upon it." He also concludes regarding contraception (quoting another CT author) that "The burden of proof rests, then, on the couple who wish to restrict the size of their family."

In the article following in the CT issue Dudley notes, Fuller Seminary Theologian Paul Jewett looked at the theological, historical, psychiatric, and sociological dimensions of the abortion issue. He concludes that "there are difficulties … moral theology faces in justifying abortion." And "It seems the Christian answer to the control of human reproduction must be found principally in the prevention of contraception, rather than the prevention of birth."

Dudley is formally right in this regard: Note how Jewett ends: "Abortion will always remain a last recourse, ventured in emergency and burdened with uncertainty." Still, this sounds to me very much like early apologies for slavery, when some northern Christians imagined slave owners as benevolent masters of an inferior people. Once the horrors of slavery became known and the humanity of African-Americans became evident, northern Christians increasingly become single-minded in their opposition to slavery. That has more or less been the history of contemporary evangelicalism regarding abortion. When it was indeed a rare occurance, most of us could imagine an exception here and there. When it turned into the wholesale slaughter of millions (54 million since 1973 in the US alone), we have naturally become as little less flexible about it.

(One of the finer moments in CT history is our early 1973 editorial clearly denouncing Roe v. Wade: "This decision runs counter not merely to the moral teachings of Christianity through the ages." At the end, there was also this prescient comment: "Christians should accustom themselves to the thought that the American state no longer supports, in any meaningful sense, the laws of God, and prepare themselves spiritually for the prospect that it may one day formally repudiate them and turn against those who seek to live by them.")

Still, Dudley concludes, "Before casting their ballots … evangelicals would benefit from pausing to look back at their own history. In doing so, they might consider the possibility that they aren't submitting to the dictates of a timeless biblical truth, but instead, to the goals of a well-organized political initiative only a little more than 30 years old."

Earlier this month, Letha Dawson Scanzoni, made the same point on the FemFaith blog ("an intergenerational Christian Feminist Conversation"). She added illustrations from the famous Baptist preacher W. A. Criswell (which she garnered from Randall Balmer's Thy Kingdom Come: How the Religious Right Distorts Faith and Threatens America). Apparently Criswell once said regarding the Supreme Court's Roe v. Wade 1973 decision, "I have always felt that it was only after a child was born and had a life separate from its mother that it became an individual person, and it has always, therefore, seemed to me that what is best for the mother and for the future should be allowed."

So, yes, evangelicals were at large still figuring things out back in the 1960s and 1970s—before the deluge began. The fact that a view has gained ground in 30 years is no argument for it or against it. To suggest that a new view is suspect just because it's new—well, it's ironic that people who would otherwise happily call themselves liberal would be so conservative when it comes to the history of ideas.

It should not surprise anyone with a real acquaintance with history, especially religious history, that people of faith often come to firm and unshakable convictions only after a period of reflection and debate. It took the church some three centuries to firmly settle in on the doctrine of the Trinity, and another 15 to fully recognize the evils of slavery. In this light, American evangelicals were on the fast track: Assuming they first became a recognizable movement within Christianity during the Great Awakening, they only took 250 years to recognize the evil of abortion.

A careful reading of our history suggests not that evangelical convictions are the result of a "well-organized political initiatve," but that these initiatives grew out of our increasingly wide spread and deeply held moral convictions and deepening awareness of the number of lives being cast away (over a million a year since 1976). To be sure, once the evangelical anti-abortion movement got started, politics reinforced ethics, and vice versa. But as one embedded in the movement for nearly half a century–and one who has been often troubled by the ham-fisted anti-abortion politics of the Religious Right—there is no doubt that the ground of anti-abortion politics is moral conviction and a bloody historical reality.

What seems especially hypocritical and disingenuous is this: No one, let alone these authors, would argue that 30 years ago, Americans were much more divided about women's rights, and therefore feminists should be open to other points of view. In particular, thanks to the work of Nicolas Kristof (Half the Sky) and our own Marian Liataud (note her "War on Women" in the December issue), we are becoming increasingly aware of the terrible holocaust against girls–the result of gender selected abortions, sex trafficking, and brutal cultural practices across the globe. As Liatuad notes in her forthcoming ebook on the topic (December release as well), "In the time it took you to read the previous paragraph, a baby girl's life was ended by sex-selective abortion. In another hour, 114 more baby girls will be abandoned simply because they are girls." She says that while the number of people lost to AIDS stands around 25 million, the number of girls lost to gendercide is closer to 168 million.

Are we really to champion, as Scanzoni does, being open to "differing viewpoints" and "a humility of spirit" when discussing such "tough moral and ethical questions"?

I hope not.

Mark Galli is editor of Christianity Today.