Next time you're with a group of evangelical Christians, try this exercise in free association: What comes to mind when you hear the word "gay"? Whose faces do you imagine? The lesbian couple who live next door, who have been burned by the church and have been dropping hints that they're not too fond of Christians? The barely-clad, gyrating figures in the local Pride Parade? The political activists you watch on the nightly news? The radio show host who said those nasty things about conservatives?

Whatever pictures the label "gay" evokes, you probably don't immediately envision the face of an evangelical churchgoer. Justin Lee, a self-described "gay Christian" and author of the disarmingly vulnerable Torn: Rescuing the Gospel from the Gays-vs.-Christians Debate (Jericho Books), is out to change your perceptions.

Known as "God Boy" in high school, Lee was the kid who wouldn't shut up about Jesus. He came from good evangelical stock: Raised Southern Baptist, in a picture-perfect family, he was outspoken and winsome in a leadership role in his church's youth group. Yet while he was defending his church's traditional position on gay partnerships ("love the sinner, hate the sin," he once repeated to a skeptical fellow student, only to regret it afterwards), Lee was harboring a secret. "Years earlier," he writes, "when I had first hit puberty and all my male friends were starting to 'notice' girls, I was having the opposite experience: I was starting to 'notice' other guys."

At first he tried chalking this experience up to a phase many young men his age went through. He dated girls, focused on his schoolwork, and stayed busy with church activities. But his attraction to other guys didn't diminish or recede. In a particularly poignant passage of his book, Lee recalls holding hands with his girlfriend at a Michael W. Smith and Jars of Clay concert when, in an unbidden moment, he found himself staring at a guy. "I only saw him for an instant," Lee says, "but I couldn't help noticing his attractive features, and suddenly I found my thoughts and emotions rushing toward him. I wanted to know everything about him …. I wanted to meet him, to talk to him, to get to know him, to spend time with him."

Eventually, Lee admitted to himself—and then, later, to his pastor, his parents (whom his book describes as notably mature, compassionate, and sensitive), and a small cadre of trusted friends—that what he was experiencing wasn't just a phase, or a glitch caused by faulty parenting, or an overcharged sex drive. It was something far more quotidian—but also, by the same token, far more central and identity-shaping—than any of those things. Where his friends wanted to spend time with women and (eventually) fall in love, Lee wanted to know and love a man.

Here to Stay

As Lee began telling his story to others, he started to meet more people like him: kids who had grown up in Christian homes, remained Christian believers, and yet found themselves with persistent, apparently unchangeable, same-sex attractions. What was God's will for these new friends? Should they try to rid themselves of their homosexuality? (Lee eventually decided "no." A good chunk of his book is spent discussing his experiences of duplicity and false hope in and among "ex-gay" ministries.) Over a long period of prayer and frank conversation with his fellow believers, Lee came to think that he and other gay Christians should be able to express their feelings for a member of the same sex.

Where did that leave Scripture's prohibitions of homosexuality? For Lee, the answer to that question hinged on how to interpret Jesus' teaching about the centrality of love. True, he recognized, a few biblical passages do condemn homosexual partnerships, but those relationships appeared to be marred by exploitation or idolatry. (This is how Lee reads Romans 1, for instance.) Above all, there was Jesus' more compassionate teaching about love being the fulfillment of the law. If Jesus castigated the Pharisees for tying up "heavy, cumbersome loads and put[ting] them on other people's shoulders" (Matt. 23:4), what would he say to those who asked gay people to live without love?

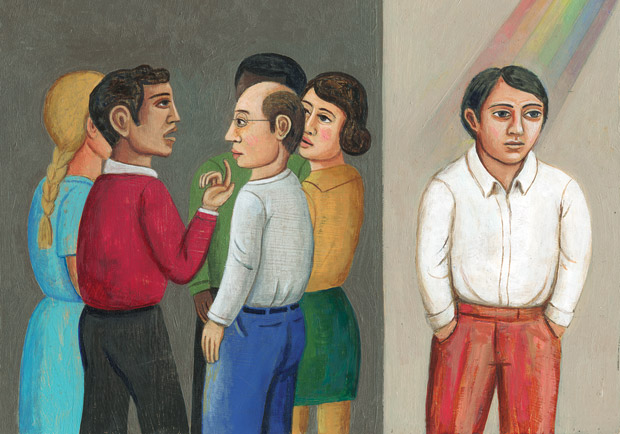

Surely gays and lesbians are 'out there', somewhere else, not 'here' in our discipleship small groups, or kneeling at the Communion rail beside us—are they?

Out of these convictions, Lee started a ministry, first online and now involving a yearly conference, a regular podcast, and countless speaking engagements, blog posts, and one-on-one conversations: the Gay Christian Network (GCN). The closeted kid who had been the model evangelical child now became the public face of one of the country's up-and-coming gay advocacy groups.

Many of us evangelicals may believe that LGBTQ ("lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning") folks are far removed from our churches and ministries. Surely gays and lesbians are out there, somewhere else, not here in our discipleship small groups, or kneeling at the Communion rail beside us—are they? But if Lee, the God Boy of his high school who could quote John 3:16 in his sleep, is an example of what it means to be "gay," then yes, they are. They're here in our churches, and they're here to stay, forcing us to reconsider what it might mean to love our own spiritual siblings.

For his part, Lee is in no doubt about what form that love ought to assume. "Openly gay Christians must find their place throughout the church," he writes. Appealing to the dispute over food that Paul had to confront in the churches he founded (Rom. 14), Lee suggests that we follow Paul's counsel not to quarrel "over disputable matters." Those who believe in good faith that God allows for permanent, monogamous gay relationships (what Lee calls "Side A") and those who believe gay Christians ought to remain celibate ("Side B") can learn to treat one another as brothers and sisters in Christ who disagree over a matter of conscience.

A Place of Transformation

Full disclosure: I am a celibate gay Christian. Like Lee, I grew up Southern Baptist. Like him, I discovered during puberty that I was exclusively attracted to others of my own sex. But unlike Lee, I don't find any wiggle room in Scripture: Marriage is intended for one man and one woman (Gen. 2; Matt. 19; Eph. 5), and anyone living outside that marital state is called to celibacy (1 Cor. 7).

Lee's book leaves people like me—his fellow gay Christians who, nonetheless, disagree sharply with him on sexual ethics—in a difficult position. On the one hand, we share his hope that the church may be a place of welcome and grace for LGBTQ people. However, we don't view our celibacy as simply one option among an array of valid choices which believers are free to sort out as they please. Rather, we see celibacy as obedience to the clear, if bracing, mandate of Scripture. And we've found the church to be a place of transformation, a place to be, in T. S. Eliot's words, "renewed, transfigured, in another pattern."

It's tempting, with Lee, to think that Jesus' ethic of love abrogates some of the more obscure or challenging biblical norms. Yet the sweep of the canon of Scripture suggests that we follow Jesus rightly when we see the apostles' teaching and commands as flowing from Jesus' love for us, not impeding it. "If you love me, you will keep my commandments," Jesus told his disciples (John 14:15, esv). Conforming our lives to Scripture's difficult ethical teaching is precisely the way we demonstrate that we've made our home in Jesus' love. And that's a path that Lee's book, for all its commendable honesty and salutary insight, chooses not to explore.

Wesley Hill, author of Washed and Waiting: Reflections on Christian Faithfulness and Homosexuality (Zondervan), is assistant professor of New Testament at Trinity School for Ministry in Ambridge, Pennsylvania.