After the Beatles broke up and went their separate ways, George Harrison fretted about transitioning to a solo career—but that anxiety was often quelled by a deep, inner faith.

“I’d be going through some private nightmare,” he tells longtime friend Ravi Shankar in George Harrison: Living in the Material World, newly released to DVD. Harrison would wonder how he could possibly enter a Krishna temple in such a frenzied, depressed state: “But then I’d go, and I’d always walk out of there thinking, ‘Oh, thank you Lord.'”

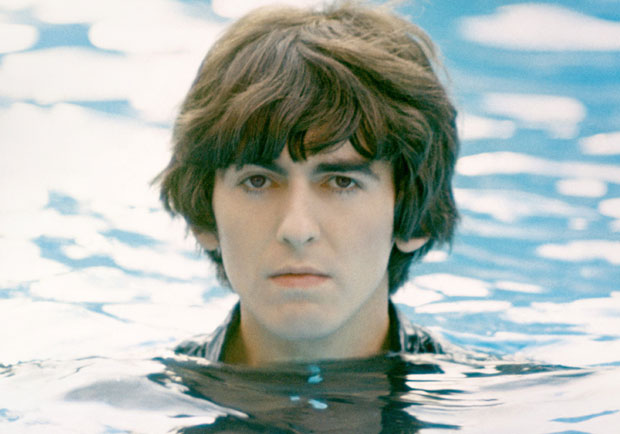

It’s just one of many insights into the “quiet” Beatle’s intense spiritual search in the compelling, cradle-to-grave documentary by Martin Scorsese. The 3½-hour film aired on HBO last fall.

Harrison may have kept a lower profile than fellow Beatles John and Paul (and even Ringo), but his inner world was anything but static. Harrison’s spiritual quest tellingly commenced during the Fab Four’s apogee (when all the fame and fortune wasn’t bringing him peace) and continued in some respects for the rest of his days.

While Scorsese’s film does a splendid job underscoring how greatly Harrison’s spiritual journey informed his uncommon convictions about life, death, and the soul, more than half of it focuses on the well-trod territory of George’s early life through the Beatles’ breakup. Since I eagerly gobble up new stuff about the Liverpool lads whenever I can, I don’t mind that all. And even though Scorsese fills the screen with a bevy of George’s personal photos, some rare footage, and new interviews with the likes of McCartney, Ringo, and Eric Clapton, much of the doc’s first half could have been shortened and positioned to set up Harrison’s far more compelling post-Beatle life.

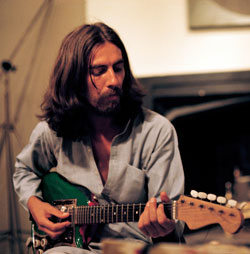

In fairness, though, one fact about Harrison’s late-Beatles career was worth keeping in the film: His admitted anxiety during this period wasn’t about what he’d do if the band broke up, without the other three to lean on. Rather, Harrison had stockpiled tons of songs (the Lennon-McCartney team left little room for George’s tunes), and he grew distressed that as the wounded quartet plodded on, his growing catalog might never see the light of day.

Harrison didn’t dread the Beatles’ looming breakup—he couldn’t wait for it to happen. He knew it would turn him loose emotionally, mentally, personally, and musically. And as the film points out, Harrison was already well on his way toward spiritual freedom as he defined it. But like most of us who embrace faith in some form, George had his ups and downs—like those “private nightmares” noted above, followed by a spiritual peace.

Having sworn off LSD, Harrison notes that meditation and chanting became alternate paths toward consciousness shifting and getting in greater touch with the soul. Mukunda Goswami, a friend and fellow Hare Krishna disciple, says Harrison wanted to get the Hare Krishna mantra recorded and released as a 45-rpm single in the summer of 1969 because he “wanted to get across what he believed through a medium he was familiar with.” Harrison and his brethren didn’t think anything would come of the single, but it became a hit, appearing high in the English charts—as well as during intermissions at the Isle of Wight festival and a huge Manchester United soccer match, thousands of fans singing along to the familiar two-word chant.

‘A lotta people are gonna hate me’

It’s surprising to learn that Harrison was initially reluctant to record “My Sweet Lord” for his debut solo effort, the acclaimed 1970 triple album All Things Must Pass. “It’s really committing myself to something,” Harrison says of the tune and its prominent use of the Hare Krishna mantra. “There’s gonna be a lotta people who are really gonna hate me. Because people fear the unknown, you see. The point was that I was sticking my neck out on the chopping block.”

But producer Phil Spector—who also worked on the Beatles’ Let It Be—insisted not only that “My Sweet Lord” make it to tape but also that it should be the album’s single. Spector says on film that he told Harrison it didn’t matter what “My Sweet Lord” was about—it was George’s most commercial track. Spector also observes that Harrison lived out his beliefs, that there was “no salesmanship involved. It made you spiritual just being around him. It made you like those Krishnas, who could sometimes be the biggest pain in the necks in the world, running around with their robes and shaved heads and white powder all over their faces, scaring you half to death coming out of a dark studio, glowing.”

More than a few interviewees note Harrison’s determined, at times defiant, nature, most notably when it came to his main spiritual thrust: The ultimate goal of seeing his body, possessions, and the earth itself pass away to make room for whatever was next.

Still, after Harrison was diagnosed with cancer in 1997 and nearly murdered in his home by a deranged, knife-wielding intruder in 1999, he confessed to his wife Olivia that he still wasn’t where he wanted to be spiritually. “I better start letting go of this life,” she recalls George telling her. “I better start doing what I’ve been practicing to do my whole life so that I can leave my body the way I want to.”

When Harrison lost his battle with cancer on November 29, 2001, Olivia says “there was a profound experience that happened when he left his body. It was visible. Let’s just say that you wouldn’t need to light the room if you were trying to film it. He just lit the room.”

Admirable faith

How Harrison lived out his spirituality is admirable on many levels. As a Christian, I don’t share his beliefs and conclusions, but I can learn much from how he dispensed with the trappings of our earthly existence (figuratively at least; he left 100 million British pounds—or about $163 million US—to his heirs), how passionately he pursued his faith, and especially how he faced death.

Monty Python’s Eric Idle, a close friend of Harrison’s, resonated with how the musician viewed life and death. Idle, if you recall, composed and sang the famous ditty, “Always Look on the Bright Side of Life,” which reflects a kind of throwaway perspective on death (and closed the controversial Python movie Life of Brian, which Harrison financed). “Existence is kind of funny because of our temporality,” Idle says onscreen. “It’s all, ‘Here we are, going around pretending to be kings and emperors,’ and you’re gonna die. You’re in a box in a minute or two. So we are constantly undercut by our own physicalities, our own physical bodies, which let us down.”

By all accounts, Harrison didn’t fear his demise. Rather it appears he looked forward to it, spiritually rehearsing for that inevitable moment so he could give a great performance when the curtains parted—quite an amazing perspective from one who didn’t have or seek hope in Jesus. It’s nevertheless reminiscent of Paul’s absent-from-the-body-present-with-the-Lord encouragement from 2 Corinthians 5, and so it compels me to ask how consistently the collective “we” of Christ’s church live out that hope.

Because after all the music and footage and interviews that reveal who Harrison really was, that’s the question still sticking in my head and heart. And it’s a good question—because I know I don’t live out that hope nearly enough.

Copyright © 2012 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.