Central to the beauty and power of the ballet Swan Lake—of which Black Swan is a sort of contemporary, hallucinatory offspring—are contrasts and dynamics, complimentary parts of a yin-yang whole: Light and dark, good and evil, soft and loud (as in Tchaikovsky’s famous music). When the ballet is performed, one ballerina plays both the heroine Odette (“The White Swan”) and her evil foil/doppelganger Odile (“The Black Swan”). It’s a dream role, to be sure, but supremely challenging to pull off. The dual parts require the performer to simultaneously attune to her inner darkness and light, hopping back and forth between dialectical extremes, to the delight of audiences enthralled by the bravura embodiment of such range and passion. It’d be enough to make any ballerina go insane.

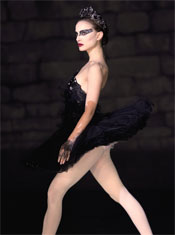

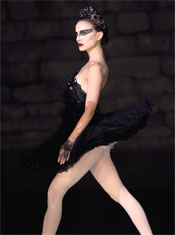

Darren Aronfosky’s Black Swan is about Nina (Natalie Portman), an ingénue ballerina in a New York City company who lands the coveted White/Black Swan role after the reigning prima (Winona Ryder) is dismissed on account of being too old. Nina is a tightly wound, sweetly mannered perfectionist with a crazy-eyed stage mom (Barbara Hershey), so naturally she takes her prized star turn extremely seriously. In the lead up to her big debut, Nina’s fixation on giving the audience the perfect performance begins to consume her. (Fitting that the film’s official website is ijustwanttobeperfect.com.) She becomes obsessed with her weaknesses and paranoid that her understudy (Mila Kunis) has an eye on sabotage. When the ballet director Thomas (Vincent Cassel) tells Nina that her Black Swan is less than convincing, she becomes fixated on tapping into her own dormant or undiscovered darkness. And this is when things really start to spin out of control.

IMG_5182.CR2

IMG_5182.CR2If you’ve seen Aronofsky’s Requiem for a Dream or Π, you’ll know some of what you’re in for with Black Swan. It’s a psychological thriller full of paranoia, hallucinations, dream sequences, quick-cut shock shots, and a steadily increasing distrust of reality. How much of what we are seeing is real? How much is simply in the mind of Nina? Is there ultimately any difference?

As heady and surreal as Black Swan turns out to be, its closest kin in the family of Aronofsky films is the director’s most recent work, 2008’sThe Wrestler. In addition to sharing similar visual styles (muted, cold colors and handheld camerawork), both films concern protagonists who make a living sacrificing their bodies for the thrill and pleasure of audiences. Aronofsky has said in interviews that Swan could be considered a companion piece to The Wrestler, and that both stemmed from an original concept he had for a movie about a romance between a ballet dancer and a professional wrestler.

IMG_5857.CR2

IMG_5857.CR2Indeed, taken as a pair, Swan and The Wrestler seem almost like a diptych exploration of gender, embodiment, and how we understand the self in and through vocation. In The Wrestler, Mickey Rourke played a steroid-pumping professional wrestler in search of an authentic persona apart from the prescribed cultural tropes of hyper-masculinity and machismo, through which he had made a career. In Black Swan, Portman’s Nina is similarly trapped inside cultural notions of femininity and beauty. The ubiquitous mirrors in her life constantly remind her of the importance of a girlish figure and a graceful pose. Her bedroom is all dolls and her wardrobe mostly pink, dainty and Victorian to the core.

Insofar as Black Swan is a musing on societal pressures to conform to a norm of femininity and “perfect” beauty, it’s a fascinating and moving film, and an excellent companion to The Wrestler. We feel for Nina, because we know what it’s like to want desperately to please people, to win acclaim, and to be beautiful. And yet with Swan, Aronfosky opts not to match the restrained realism of The Wrestler, instead going the route of madhouse phantasmagoria, complete with horror-genre flourishes (jumps, scares, stabbings, frenzied fingernail clippings) and feverish lesbian nightmares. The result is a sometimes maddening, slightly overwrought spectacle that would have been better off had the hallucinatory freakshow elements been toned down just a bit.

IMG_7023.CR2

IMG_7023.CR2The life-imitating-art, “is she actually becoming the Black Swan?” conceit definitely has its moments, and certainly the stylistic grandstanding it affords Aronofsky and longtime collaborators Matthew Libatique (cinematography) and Clint Mansell (music) produces frequently spectacular results. The overall look and feel of the film—an after-dark labyrinth of urban aristocracy somewhat reminiscent of Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut—is gorgeously sinister. But by the time we reach the bombastic, over-the-top finale, it all becomes just a tad bit too much.

The creepy ambience and disturbing undertones of Black Swan could have been achieved without the various David Lynch-esque surrealist indulgences. It’s a shame that what could have been a truly unsettling, insightful portrait of a woman racked by insecurities, jealousy, paranoia, and perfectionism was tarnished by an impatient insistence on reducing Nina’s interior conflicts to creepy visions and lurid dream sequences. Make no mistake, Portman gives a stellar performance here; but it could have been even better had she had not been obligated to run around with terrified bloodshot eyes and black feathered wings growing out of her back for much of the film’s third act.

In spite of all this, Black Swan still stands as a superbly acted, artfully composed film unlike most anything else you might see this year. Flaws aside, Swan has a serious mind and sincere heart, rooted in a perceptive analysis of the psychological effects of a culture of perfection and performance.

Somewhere in the showbiz ancestry of this film is that horrifying Fox reality show from 2004, The Swan, and the nip/tuck culture that spawned it. In such a world—where the self is only as good as its proximity to normative beauty—our already fragile identities are further weakened by an unceasing barrage of images and declarations of desirability. Black Swan doesn’t preach about any of this as much as it riffs, runs, and dances with the darkness of it, sometimes insightfully and sometimes ridiculously.

Talk About It

Discussion starters- Why is Nina so obsessed with being perfect? What factors in her life and in society lead her to this pressure? What does Scripture say about true beauty?

- How does the plot and theme of Swan Lake compare or contrast to that of Black Swan?

- If you have seen The Wrestler, how does Black Swan work as a companion piece?

- Is there value in acknowledging the coexistence, even within our self, of both good and evil? How should Christians approach the repression of our baser instincts?

The Family Corner

For parents to considerBlack Swan is rated R for strong sexual content, disturbing violent images, language and some drug use. It’s frightening and disturbing and not appropriate for children. An overall mood of darkness and flirtation with evil pervades the film, with plenty of disturbing scenes of violence and blood to show for it. Though there is not really any explicit nudity, the film also contains several sex scenes, including a lesbian sex scene between two of the main actresses. Drug use and a fair amount of explicit language also underscore that this is a film for adults only, not recommended for younger audiences or those in the mood for an innocent ballet movie.

Photos © Fox Searchlight.

Copyright © 2010 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.