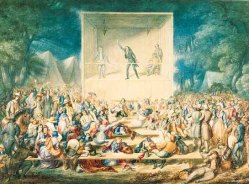

The emotional energy of Cane Ridge and other early frontier revivals arose from a strong emphasis on the Eucharist.

Many evangelicals – especially younger ones – are today re-engaging tradition. Other evangelicals worry about this re-engagement. They feel that to move toward a more liturgical form of worship or a more fixed, detailed style of theological “confession” is to give up the freer, more emotional worship style or more grass-roots, straightforward doctrinal and theological style won for us by such evangelical forefathers as the 18th century’s John Wesley or the 19th century’s Charles Finney.

I want to suggest that one way forward to healthier engagement with tradition for modern-day evangelicals is through a look at our own recent past. For American revivalism itself grew on unexpected foundations of liturgy and doctrinal confession.

As for liturgical and indeed sacramental worship: few evangelicals know that the drawing power and emotional energy of such early frontier revivals as the one at Cane Ridge, Kentucky in 1800 – which set the stage for a century of explosive evangelical growth – arose from a strong emphasis on the Eucharist. It’s true! Those deeply emotional and highly demonstrative camp-meeting revivals were in fact multi-day “Eucharistic seasons,” in the tradition of old-world Scotch-Irish Presbyterianism (See Leigh Eric Schmidt, Holy Fairs: Scotland and the Making of American Revivalism, 2nd ed. [Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1989]). A similar Eucharistic focus characterized the revivalistic “melting times” of exuberant worship and deep christocentric mysticism in the early American Methodist quarterly camp meetings (Lester Ruth, A Little Heaven Below [Nashville, Tenn.: Kingswood Books, 2000]).

This seriousness about the Lord’s Supper in fact goes back before the early 19th-century revivalists to the people who may reasonably be called the “co-founders” of evangelicalism: John Wesley and Jonathan Edwards. Both of these men, Wesley in Georgia and Edwards in Northampton, Mass., got themselves into hot water with congregations they were ministering to – for the same reason: they “fenced the table” to keep out those not prepared (sacramentally or ethically) to participate in the Lord’s Supper.

As for confessional theology, many early evangelicals worked out of solid Calvinist confessional conviction. For example, New Lights who sprung from America’s eighteenth-century season of Awakening “worked to make people more theologically self-conscious, often by rewriting church covenants to include strict doctrinal standards.”

Short-lived as many of these sorts of traditional roots were, they did shape evangelicalism in its American cradle. Even the brash New Measures revivalist, Charles Finney, recognized that he built on the foundations of “the evangelical Presbyterian heritage of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries,” with its Eucharistic piety and confessional emphasis (Schmidt, Holy Fairs, 207). Again, this may prove one “way forward” to healthier engagement with tradition for modern-day evangelicals: examine points at which our recent forebears have found something valuable in liturgy, doctrine, or church order (Nathan Hatch, Democratization of American Christianity [New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1991], 180).

By looking at our own history with our eyes really, truly open, evangelicals will find that a commitment to tradition, robust theological confession, or liturgical worship is not inconsistent with the free-church commitment to every believer’s direct, unmediated access to God in worship and prayer. If you don’t believe this, I encourage you to check out CT managing editor Mark Galli’s recent case for evangelical re-engagement with liturgy: Beyond Smells & Bells: The Wonder and Power of Christian Liturgy (Paraclete Press, 2008).

One more note: this suggestion is nothing new. Check out the chapter by evangelical historian Richard Lovelace in the book The Orthodox Evangelicals, Robert Webber and Donald G. Bloesch, eds. (Thomas Nelson, 1978), and you’ll see something very much like this. Lovelace speaks of “the evangelical spirit,” and traces it back not only through the early history of evangelicalism, but back through the Reformation, to the medieval church, and into the first centuries of the early church. This is the kind of vision of continuity–long the “native perspective” of the Roman Catholics and Eastern Orthodox–that evangelicals need to recover today.

* * *

Image: “Religious Camp Meeting” by J. Maze Burbank (1839), Old Dartmouth Historical Society via Wikimedia Commons, used by permission.