On May 12, the 7.9-magnitude earthquake in China killed 100,000, dwarfing the carnage of 9/11 by 30-fold and approximating the U.S. body-bag count in World War I. Tremors were detected as far away as Vietnam, 500 miles distant.

The seismic shift rocked more than soil. Souls move too, even in Chengdu, the literal and figurative heart of China. The capital city of the affected region, Sichuan Province, is 50 miles from the quake's epicenter and is home to one of the world's 100 busiest airports, $25 billion in foreign investments, and 16 colleges.

In unprecedented response, a high-ranking Chinese official appointed Robert Yeung, a counseling educator and the only Christian among 10 colleagues, to organize psychological recovery efforts. He is the academic dean at the Hong Kong Institute of Christian Counselors (HKICC), the city's only faith-based institute for psychological care.

Three months after the quake, I sat cramped in Yeung's 8-by-6-foot office, dripping sweat in record heat while Yeung recalled the historic day.

"Two mountains collapsed and buried some towns," he said. "It was devastating. I smelled a dead body, saw broken buildings, a school collapsed, people sleeping on the sidewalk. I never saw anything like that before. People were crying. They lost spirit. No hope for them. And anger."

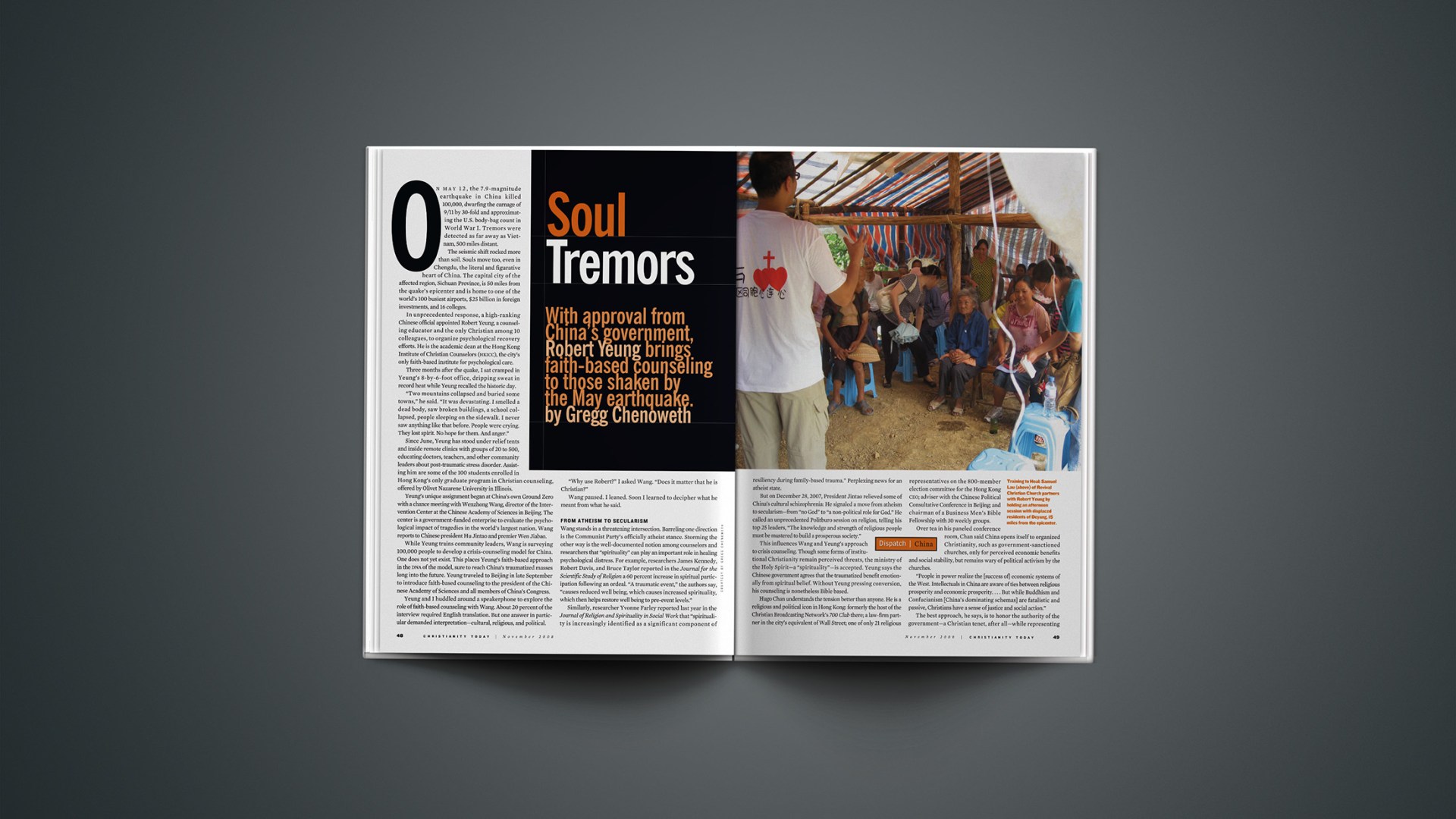

Since June, Yeung has stood under relief tents and inside remote clinics with groups of 20 to 500, educating doctors, teachers, and other community leaders about post-traumatic stress disorder. Assisting him are some of the 100 students enrolled in Hong Kong's only graduate program in Christian counseling, offered by Olivet Nazarene University in Illinois.

Yeung's unique assignment began at China's own Ground Zero with a chance meeting with Wenzhong Wang, director of the Intervention Center at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing. The center is a government-funded enterprise to evaluate the psychological impact of tragedies in the world's largest nation. Wang reports to Chinese president Hu Jintao and premier Wen Jiabao.

While Yeung trains community leaders, Wang is surveying 100,000 people to develop a crisis-counseling model for China. One does not yet exist. This places Yeung's faith-based approach in the DNA of the model, sure to reach China's traumatized masses long into the future. Yeung traveled to Beijing in late September to introduce faith-based counseling to the president of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and all members of China's Congress.

Yeung and I huddled around a speakerphone to explore the role of faith-based counseling with Wang. About 20 percent of the interview required English translation. But one answer in particular demanded interpretation—cultural, religious, and political.

"Why use Robert?" I asked Wang. "Does it matter that he is Christian?"

Wang paused. I leaned. Soon I learned to decipher what he meant from what he said.

From Atheism to Secularism

Wang stands in a threatening intersection. Barreling one direction is the Communist Party's officially atheist stance. Storming the other way is the well-documented notion among counselors and researchers that "spirituality" can play an important role in healing psychological distress. For example, researchers James Kennedy, Robert Davis, and Bruce Taylor reported in the Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion a 60 percent increase in spiritual participation following an ordeal. "A traumatic event," the authors say, "causes reduced well being, which causes increased spirituality, which then helps restore well being to pre-event levels."

Similarly, researcher Yvonne Farley reported last year in the Journal of Religion and Spirituality in Social Work that "spirituality is increasingly identified as a significant component of resiliency during family-based trauma." Perplexing news for an atheist state.

But on December 28, 2007, President Jintao relieved some of China's cultural schizophrenia: He signaled a move from atheism to secularism—from "no God" to "a non-political role for God." He called an unprecedented Politburo session on religion, telling his top 25 leaders, "The knowledge and strength of religious people must be mustered to build a prosperous society."

This influences Wang and Yeung's approach to crisis counseling. Though some forms of institutional Christianity remain perceived threats, the ministry of the Holy Spirit—a "spirituality"—is accepted. Yeung says the Chinese government agrees that the traumatized benefit emotionally from spiritual belief. Without Yeung pressing conversion, his counseling is nonetheless Bible based.

Hugo Chan understands the tension better than anyone. He is a religious and political icon in Hong Kong: formerly the host of the Christian Broadcasting Network's 700 Club there; a law-firm partner in the city's equivalent of Wall Street; one of only 21 religious representatives on the 800-member election committee for the Hong Kong ceo; adviser with the Chinese Political Consultative Conference in Beijing; and chairman of a Business Men's Bible Fellowship with 30 weekly groups.

Over tea in his paneled conference room, Chan said China opens itself to organized Christianity, such as government-sanctioned churches, only for perceived economic benefits and social stability, but remains wary of political activism by the churches.

"People in power realize the [success of] economic systems of the West. Intellectuals in China are aware of ties between religious prosperity and economic prosperity. … But while Buddhism and Confucianism [China's dominating schemas] are fatalistic and passive, Christians have a sense of justice and social action."

The best approach, he says, is to honor the authority of the government—a Christian tenet, after all—while representing Christian views inside China's systems: law, politics, and, in Yeung's case, trauma response.

Counseling on the Ground

That is why Wang paused when speaking to me. Faith-based crisis counseling cannot be sanctioned. But could it be permitted?

He proceeded carefully with long, thoughtful pauses and a self-conscious lexicon (noted with italics). "Robert is a special member for the Chinese Academy of Sciences," he states. "His training is practical, beautiful, and simple, and he does it with a humble attitude. The philosophy of the victims can affect mental health. We need to know their whole picture. So this crisis is a chance for the government and the people to become more open."

Behind the lexicon was tacit permission to respond to inquiries without preaching. For example, Wang allowed Yeung to provide nametags to volunteers with the word Christian or chaplain under the name. Some relief trucks indicated the same.

However, such demonstrations can backfire. In a village near the site of the quake, the local government permitted Christian signage near a relief shelter, but some operators withdrew bottles of water from victims who rejected their preaching, bringing the faith into ill repute. This influenced Yeung's approach.

"We weren't there to preach," he says. "In fact, that is the wrong time to do it," since victims counseled about a loving God are thrown into paradox as to why he permitted tragedy. "But if they asked [about the nametags], we talked openly."

In Deyang, a city of four million south of the earthquake's trail, Yeung visited a casualty camp. Walking toward him was a 50-year-old man. "He took interest in my badge and asked what it stood for," said Yeung. "I said to him, 'I'm not here to preach to you, nor am I interviewing you. I am here to help you by talking.' "

When it was time to leave the camp, Yeung asked the man, "Since I didn't bring anything tangible to give you, can I leave you my peace?"

"Yes."

"Can I pray with you?"

He nodded.

In Chengdu, Yeung met Lily, a 12th-grade teacher who suffers nightmares for being absent from school the day of the quake. Nearly all of her students died. Yeung helped her accept the comfort of God. "I used the faith-based tactic to help Lily realize there was a missing link in her trauma," he said. "She knew about my belief and faith, and did not resent it." He explained to her, "Spirituality is being, religion is doing."

'Plug into Christ'

Yeung learned that concept from Michael Haynes of Temple, Texas. After counseling the affected at Ground Zero and victims of the Oklahoma City bombing years earlier, Haynes formed the Faith Based Counselor Training Institute to certify crisis chaplains. Yeung's HKICC brought him to Hong Kong to train any willing participants.

On an evening mid-week, I sat awestruck as one of Hong Kong's largest sanctuaries—the interdenominational Revival Christian Church (RCC), founded by Anglo missionaries—drew crowds from simple word-of-mouth advertising to hear Haynes speak. Seats for 800 filled 20 minutes prior to the event, and another 100 sat on the floor and in the foyer.

"Eighty percent of people in trauma have spiritual questions," Haynes told them. "Who will give the answers? There were 250,000 Chinese soldiers on the scene in Sichuan to do search and rescue, but they were not trained to shore up emotions or deal with anything of a spiritual nature." The key, he said, is "a ministry of presence."

"A lamp on a summer night attracts bugs just by being there. Just 'being.' Not 'doing.' But that lamp can't shine unless it is connected to electricity. So that's what we do: get where you belong; plug into Christ; shine; and draw whomever God will bring to you."

About 150 signed up for a three-day training for certification. Katherine Balcombe, cofounding pastor of rcc with her husband, Dennis, was not surprised.

"The earthquake woke up the church," she said after the event. "There is a real sense of harvest here now. [In Hong Kong] there used to be a lot of denominational lines and event labels concerned with that, but not now. There is unity."

Yeung has awakened, too. "This is definitely a highlight in my life. I see God's hands in it, opening a door to China. Everything happened in such a small amount of time, but the impact can be so big. You know it is God."

Apparently, not all earthquake aftershocks are bad.

Gregg Chenoweth is vice president for academic affairs at Olivet Nazarene University in Bourbonnais, Illinois. His work has appeared in the Chicago Tribune, The Detroit News , and various magazines.

Copyright © 2008 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

Christianity Today also wrote about relief efforts and interviewed Franklin Graham about his outreach in China after the earthquake. CT also has a special section on China.