Bob Cochran came to faith in the early 1970s as a first-year law student at the University of Virginia. His life transformed, the son of a Baptist preacher contemplated leaving law school to go to seminary. At that time, he could imagine no way to express his newfound faith as a lawyer.

Fortunately, Tom Shaffer, a Notre Dame professor who would later write On Being a Christian and a Lawyer, came to Virginia as a visiting professor. A seminar on law and religion met at his home, opening in prayer (Cochran imagined university founder Thomas Jefferson’s distress), and ending with beer. Says Cochran: “It was an eye opener.” Cochran began to understand how his legal career could be a Christian vocation—an understanding he has spent most of his career developing and passing on to others.

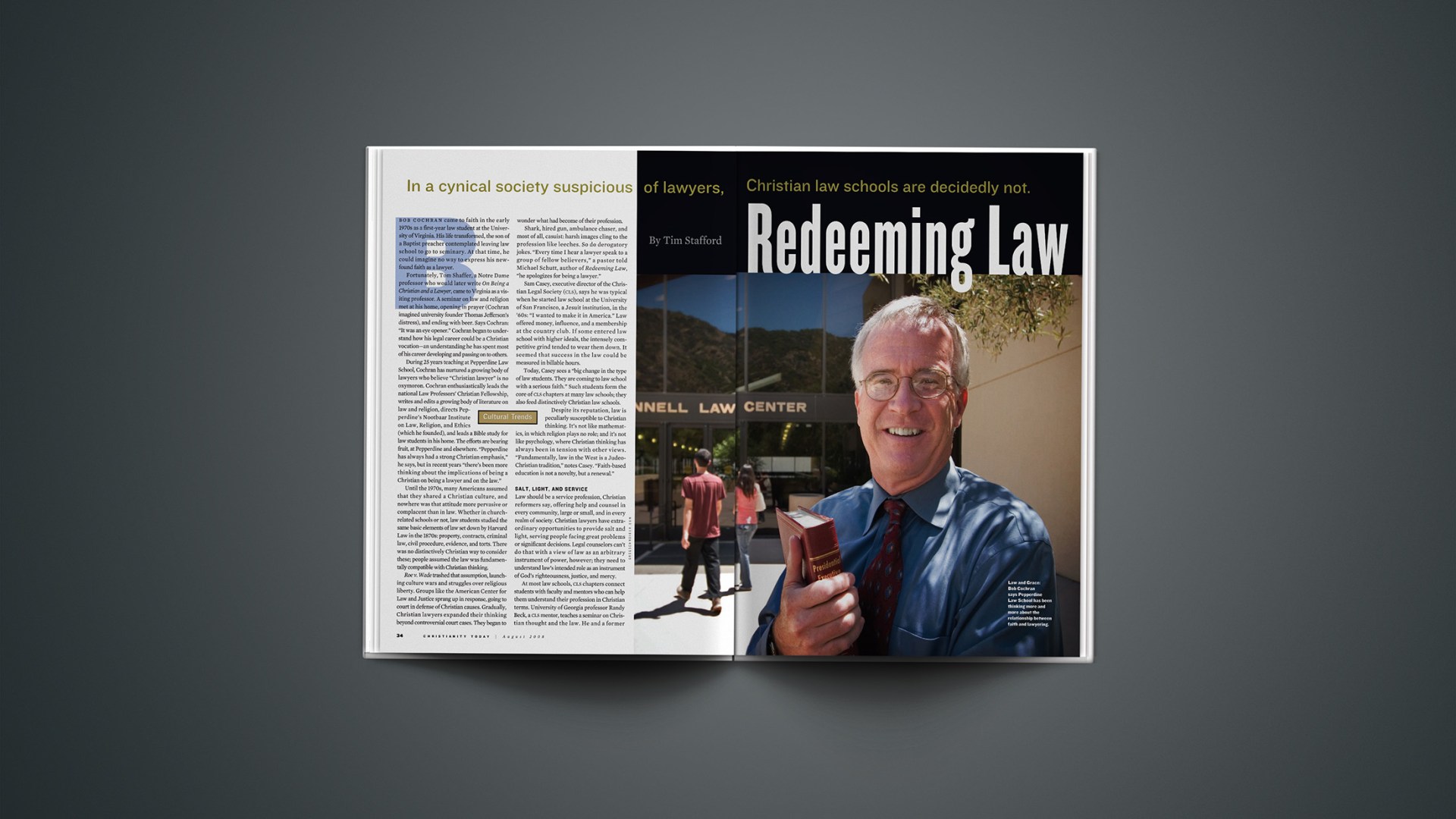

During 25 years teaching at Pepperdine Law School, Cochran has nurtured a growing body of lawyers who believe “Christian lawyer” is no oxymoron. Cochran enthusiastically leads the national Law Professors’ Christian Fellowship, writes and edits a growing body of literature on law and religion, directs Pepperdine’s Nootbaar Institute on Law, Religion, and Ethics (which he founded), and leads a Bible study for law students in his home. The efforts are bearing fruit, at Pepperdine and elsewhere. “Pepperdine has always had a strong Christian emphasis,” he says, but in recent years “there’s been more thinking about the implications of being a Christian on being a lawyer and on the law.”

Until the 1970s, many Americans assumed that they shared a Christian culture, and nowhere was that attitude more pervasive or complacent than in law. Whether in church-related schools or not, law students studied the same basic elements of law set down by Harvard Law in the 1870s: property, contracts, criminal law, civil procedure, evidence, and torts. There was no distinctively Christian way to consider these; people assumed the law was fundamentally compatible with Christian thinking.

Roe v. Wade trashed that assumption, launching culture wars and struggles over religious liberty. Groups like the American Center for Law and Justice sprang up in response, going to court in defense of Christian causes. Gradually, Christian lawyers expanded their thinking beyond controversial court cases. They began to wonder what had become of their profession.

Shark, hired gun, ambulance chaser, and most of all, casuist: harsh images cling to the profession like leeches. So do derogatory jokes. “Every time I hear a lawyer speak to a group of fellow believers,” a pastor told Michael Schutt, author of Redeeming Law, “he apologizes for being a lawyer.”

Sam Casey, executive director of the Christian Legal Society (cls), says he was typical when he started law school at the University of San Francisco, a Jesuit institution, in the ’60s: “I wanted to make it in America.” Law offered money, influence, and a membership at the country club. If some entered law school with higher ideals, the intensely competitive grind tended to wear them down. It seemed that success in the law could be measured in billable hours.

Today, Casey sees a “big change in the type of law students. They are coming to law school with a serious faith.” Such students form the core of cls chapters at many law schools; they also feed distinctively Christian law schools.

Despite its reputation, law is peculiarly susceptible to Christian thinking. It’s not like mathematics, in which religion plays no role; and it’s not like psychology, where Christian thinking has always been in tension with other views. “Fundamentally, law in the West is a Judeo-Christian tradition,” notes Casey. “Faith-based education is not a novelty, but a renewal.”

Salt, Light, and Service

Law should be a service profession, Christian reformers say, offering help and counsel in every community, large or small, and in every realm of society. Christian lawyers have extraordinary opportunities to provide salt and light, serving people facing great problems or significant decisions. Legal counselors can’t do that with a view of law as an arbitrary instrument of power, however; they need to understand law’s intended role as an instrument of God’s righteousness, justice, and mercy.

At most law schools, cls chapters connect students with faculty and mentors who can help them understand their profession in Christian terms. University of Georgia professor Randy Beck, a cls mentor, teaches a seminar on Christian thought and the law. He and a former student founded a nonprofit legal clinic for students to apply one way of Christian service through law. He reckons that religious schools serve a valuable role, but it’s “also valuable to have people thinking about these issues in the context of secular institutions.” And they do. Journals, blogs, institutes, and conferences on law and religion have now proliferated in both secular and religious schools.

The 29 contributors to an outstanding Yale University Press volume, Christian Perspectives on Legal Thought (edited by Cochran, among others), come from a variety of prestigious law schools, most of which have no Christian mission. Beck notes, “There was a period of time when religious voices were not welcomed in the legal academy. Part of the response to that was to go set up alternative institutions. But even in the secular academy, there has been more willingness to allow Christianity as one of the voices at the table.”

Others see the rise of Christian law more confrontationally. “We want to infiltrate the culture with men and women of God who are skilled in the legal profession,” Jerry Falwell told the Associated Press upon opening Liberty University School of Law in 2004. “We’ll be as far to the Right as Harvard is to the Left.” Now four years old, Liberty remains strongly identified with the Religious Right. Housed in a gigantic refurbished factory, the Lynchburg, Virginia, school looms over its parking lots like a stamping mill for culture warriors.

But appearances are deceiving. Inside the factory’s walls are well-appointed, high-tech classrooms and offices. Students and faculty estimate that somewhere between a fourth and a third of the school’s 165 students see their future as culture warriors. But that leaves the majority thinking of something more pedestrian. Students praise the warmly supportive community they experience at Liberty. They praise the 89 percent bar pass rate in their first graduating class.

Liberty emphasizes the nuts and bolts of lawyering. Dean Mathew Staver, himself a culture warrior who founded the Liberty Counsel, a religious-rights advocacy group, sees the school’s potential impact broadly, in business and medicine and intellectual property as well as in politics. “Law is so pervasive,” Staver says. “It’s strategic at every level.”

Across the state at the more elegantly styled Regent University School of Law, the vision is similarly broad. The institution has been around since 1986, when Oral Roberts University’s law school closed and gave Regent its library. Associate dean Doug Cook is at pains to point out the religious diversity of the faculty, which includes Catholics, and says that “not all are right-wing Republicans.” He says, “We probably have more graduates doing estate planning than constitutional law.”

Christian Law Schools

Of 196 American Bar Associationapproved schools, perhaps 15 claim a distinctively Christian mission, though what they mean by that varies considerably. Notre Dame, regarded as a top national school (No. 28 in U.S. News’s rankings), is one such place. It has always been distinctive among Catholic schools because its location in rural Indiana insulated it from secularizing trends and kept its faculty largely Catholic, according to professor Rick Garnett. Now it is a hub of serious legal scholarship incorporating Christian perspectives.

Not all the faculty are Catholic. John Nagle’s personal statement on the law school website states, “As an evangelical Protestant, I am more comfortable at ndls than [at] any other school that I can imagine. ndls encourages the integration of faith into teaching, scholarship, and our community life. That enables me to study biblical perspectives on land and ownership in my property class; to write about John Calvin’s references to ‘spiritual pollution’ in my book comparing environmental, cultural, and other kinds of pollution; and to accept the prayers of my colleagues and students as my family confronts a serious illness.”

Most Catholic law schools were founded not for theological reasons, but to help upwardly mobile immigrant Catholics get ahead. As Garnett says, they were like public schools in Catholic neighborhoods, demographically Catholic but otherwise secular. Some years ago Villanova’s law school dean Mark Sargent began to ask himself, “Why should the Catholic Church bother to have law schools?” He began to work toward making Villanova a place for conversations about faith and law. It has not been easy. He found that “many, if not most [faculty], are affirmatively hostile to the idea that their law school should have a meaningful Catholic mission or identity.” (One law school dean, told of Sargent’s efforts, said, “I can’t imagine what he is facing. What’s going to be thrown in his face is, ‘Do you want to become another Regent?'”)

Catholic law schools do have advantages, though. They can rely on a robust, articulate set of church teachings, from Augustine and Aquinas on down, that deals with higher law, natural law, and the application of God’s law to society. Further, a school with a Catholic vision attracts not just conservatives but also peace-and-justice activists who tend toward progressive politics. That makes for more diverse points of view, and sometimes more discord.

Most church schools educate a variety of students, but find a core identity in their particular religious affiliation. Notre Dame and its Catholic sisters aim for Catholics. Baylor and Campbell law schools educate a high percentage of Baptists. Pepperdine is distinctive because the Church of Christ, with which it is affiliated, has relatively few adherents on the West Coast, and so Pepperdine has always reached out to create a religiously diverse student body. Pepperdine overlooks the Pacific Ocean from the steep hillsides of Malibu, California, home to celebrities and millionaires. In this cosmopolitan setting the law school, led by dean Kenneth Starr, is trying to build a Christian institution with an inclusive style.

“We’re not just for Christians,” says dean emeritus Ron Phillips, who led the school until Starr stepped in. “We want to demonstrate Christianity in a law school setting.” Adds university provost Darryl Tippens, “Our model is hospitality. You believe so deeply that you are not threatened.”

So faculty members come from a wide spectrum of Protestants, Catholics, and Jews. (One professor is a rabbi.) Their politics span the spectrum, too. Pepperdine has never sought a Christian student body, yet it vies with Regent to send the most students to national cls conventions. As professor Rob Anderson says, “There’s a critical mass of students with incredible faith—living side by side with unbelievers.” Christian scholarship, says professor Douglas Kmiec, “happens naturally, not as a result of a preplanned curriculum.”

Pepperdine is on a different coast from Liberty, metaphorically as well as literally. Both are worlds apart from Notre Dame and the University of Georgia. You find the same movement at all these schools, however, and at many more. These Christian lawyers believe in something quite astonishing, given our current climate: the ennobling purpose of the law, and the servanthood of those who administer it. Abraham Lincoln’s words to lawyers capture this spirit, reminding us of how far from the ideal we have fallen:

“Discourage litigation. Persuade your neighbors to compromise whenever you can. As a peacemaker the lawyer has superior opportunity of being a good man. There will still be business enough.”

Tim Stafford is a senior writer for CT.

Copyright © 2008 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

“Unquestionable Tactics,” about a Christian lawyer’s challenges, accompanies this article.

Other articles on law are available on our website.