This will sound like an odd thing to say about a comedy, but Walk Hard is an ambitious movie. It starts with 6-year-old Dewey Cox picking up a guitar in a rural general store and belting out a blues number, and proceeds to show him singing with his polite high school band, then going through an Elvis phase, on into protest songs, Dylan-esque songs with incomprehensible lyrics, rock, hard rock, frenzied growling rock, music like the Beatles in their India phase, music like the Beach Boys—oh, you name it, it’s in there. So in addition to telling a hilarious, fast-paced story that hits all the clichés of singer-biography movies (lots of drugs, lots of rehab, lots of wives, plenty of costume changes, hairstyle changes, and the accumulating wrinkles of age), the film must also deliver spot-on music parodies.

What’s more, this is music that audience members know very, very well, so it’s not like parodying, say, Puccini. Those watching the film could sing the original models of these songs in their sleep. The performer, too, must be top-notch, and not just a good actor but a singer able to go from Bobby Darrin to Bob Dylan, John Lennon to Johnny Cash, in a heartbeat.

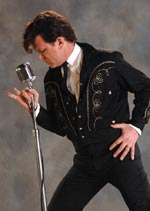

Well, it works. If only for the music numbers, this movie deserves a standing ovation. Much of the credit goes to John C. Reilly, an actor with a rubbery face and the voice of an angel. He played simple, good-hearted men in two of my favorite recent movies, Magnolia (1999) and The Good Girl (2002), but it was in Chicago (2002) that I first heard him sing, and the sweet sadness of his “Mr. Cellophane” placed a heart at the center of that frantic, heartless story.

In Walk Hard, written and produced by Judd Apatow and directed by Jake Kasdan, Reilly has to produce a seemingly impossible range of vocal styles, and does it well. The material he has to work with is excellent too, as perfect in exemplifying these many genres as the songs of “A Mighty Wind” were to the folk scene. Give the Walk Hard soundtrack album to your hippest musical friends this Christmas (the ones who don’t mind some double-entendre lyrics) and they’ll be delighted.

The story begins as Cox, now an old man, is backstage with his guitar, awaiting his cue. As he stands with head bowed, leaning against a wall, the nervous stage manager reminds him that he goes on in two minutes. But Cox’s longtime friend and his band’s drummer (an unnamed character, well-played by Tim Meadows) tells him that, before he performs, Dewey has to think about every single moment of his life. This first laugh in the film sets up a pattern: characters enunciating exactly what the film is trying to get across, as if dimmer audience members are in danger of missing it. For example, the next scene shows young Dewey and his brother Nate setting out for a day of fun. Nate keeps saying things like, “It’s a good thing I’m going to live a long, long time!” and “Nope, nothing horrible is going to happen today!” The boys end up dueling with machetes in the barn, and with one swipe Dewey cuts his brother in half at the waist; the unoccupied legs now stand beside to the top part of the torso, which is upright on the ground. Dewey tells Nate he’ll be OK, but Nate says, “I don’t know, Dewey, I’m cut in half pretty bad!” The doctor is unable to save Nate, and Dewey is so traumatized that he loses his sense of smell. “You’ve gone smellblind!” his mom exclaims.

A half-dozen years later, Dewey and his band are performing at the high school talent show, singing a mild number consisting mostly of “Take my hand.” From the first lines, however, the teens dance with abandon, while adults react with horror. “This music is an outrage!” says one, and a preacher waving a floppy Bible says, “You know who’s got hands? The Devil! And he uses them for holding things!”

I could go on citing funny lines (well, one more: Dewey’s wife complains, “But what about my dreams?” and Dewey says, “I already told you, I can’t build you a candy house”), but in the end, too many funny lines began to feel like a problem. Parody requires that the flaws of a typical music biopic be exaggerated, so the plot moves with absurd speed; good guys and bad guys are starkly distinguished, and idyllic and miserable moments follow each as swiftly as the bumps on a roller coaster track. The characters don’t have time to attain any weight of their own, and the breakneck story has no punch.

It’s only a comedy, of course, but it still could have been better. Compare Walk Hard with Anchorman (2004), another comedy produced by Apatow. The idiots and egoists who populate the TV-news world of Anchorman are hilarious, but they also have their feet on the ground as real, consistent characters, with believable (if ridiculous) motivations. Walk Hard gets to feeling more like a spray of birdshot. One joke after another comes at you, not all of them successful, and around about the middle it began to sag. This comedy is less like Apatow’s usual work (off-color comedies with some surprisingly conservative themes, like The 40-Year-Old Virgin and Knocked Up) and more like such parodies as Scary Movie, Epic Movie, or even the granddaddy of this genre, Airplane. A lot of Walk Hard is genuinely funny, and the music is truly impressive. But the substructure, the story and characters, are pretty thin.

I brought with me two youngish adult friends, who disagreed; they both thought it was hilarious, and one said it was the most she’d laughed since the first time she watched Anchorman. But, she said, next time she’d want to have the fast-forward button handy. Not only is there plenty of crude language, and a more than sufficient quantity of toilet humor (when Dewey gets his sense of smell back, he lingers joyfully over a handful of horse manure), but there is an naked orgy scene in a motel room during which a waist-down view of a man—yes, full-frontal nudity—fills a corner of the screen. The filmmakers must have thought this uproarious because the same view recurs a minute later, but most viewers will not find it particularly clever. For some potential viewers, that bit of information will be enough to decide not to see the movie at all. It’s a shame that a film with so much that is genuinely entertaining, and musically impressive, had to include a scene that will alienate viewers with a moment that isn’t even funny. Walk Hard could have traveled a lot further if it had avoided the low road.

Talk About It

Discussion starters- Movie biographies of musicians follow a standard pattern of rising success, devastation, and (in the happier cases) recovery. Is this cycle characteristic of musicians and other artists? Or is it that artists whose lives fit that storyline seem more filmable? Do you think there something in the artistic temperament that tends to induce this pattern, or is it merely the danger brought by success? Discuss.

- Many Christians would argue that shocking images can be justified in a drama that deals with serious issues. Could the same images be defended in an action or horror movie? How about a comedy?

- At one point Dewey says he is in the middle of a custody battle over his kids; he is being compelled to share custody, and he doesn’t want it, because “people shouldn’t be obligated to take on that kind of responsibility.” Do you think the character is giving voice to an opinion others hold, but won’t admit?

The Family Corner

For parents to considerWalk Hard is rated R for sexual content, graphic nudity, drug use and language. A scene of full frontal male nudity makes it inappropriate for many, including many adults who will find that sufficient grounds to skip the film. There is also a good deal of obscene language, cartoonish violence, and suggestive song lyrics.

Photos © Copyright Apatow Productions

Copyright © 2007 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.