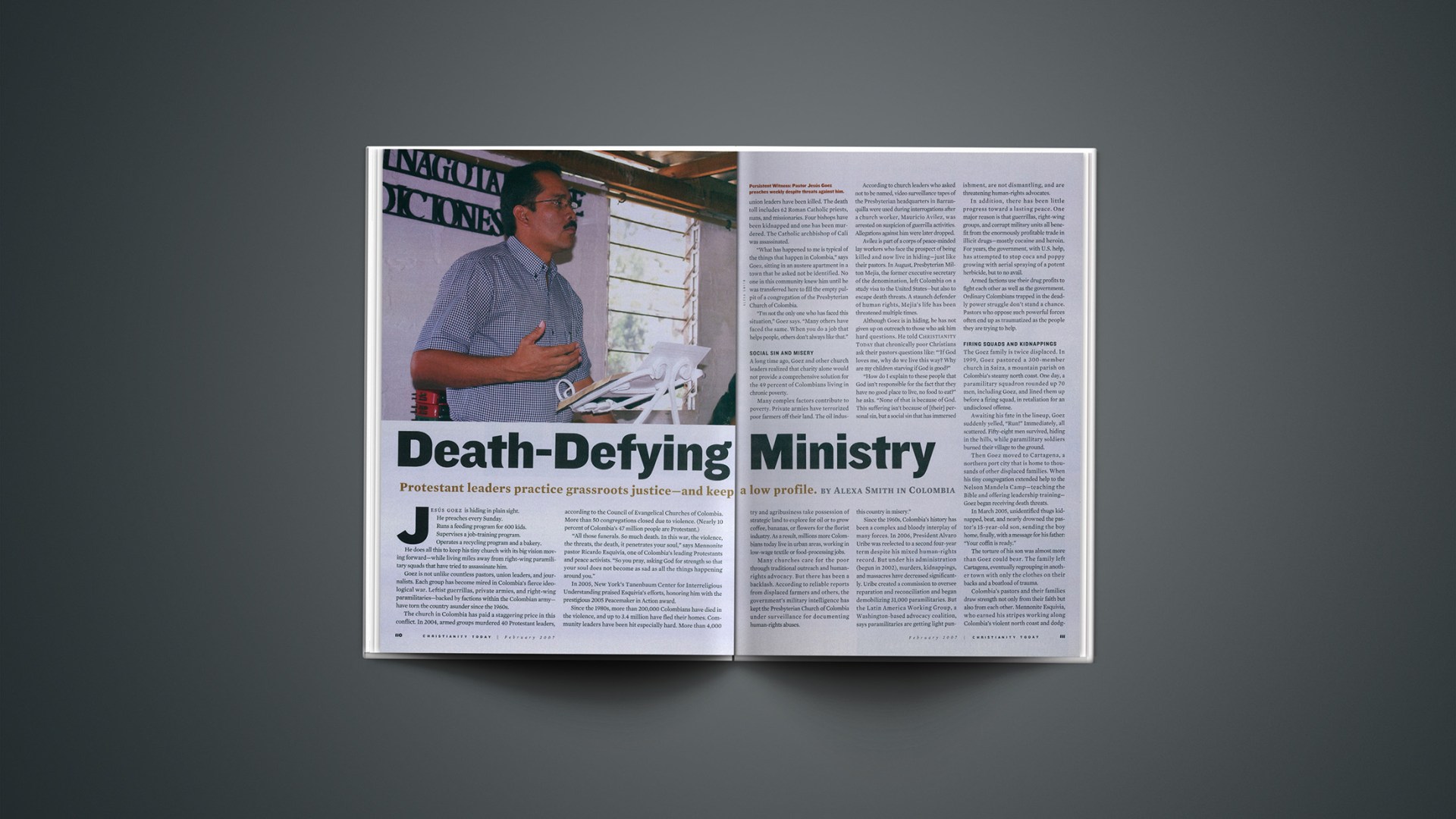

Jesús Goez is hiding in plain sight.

He preaches every Sunday.

Runs a feeding program for 600 kids.

Supervises a job-training program.

Operates a recycling program and a bakery.

He does all this to keep his tiny church with its big vision moving forward—while living miles away from right-wing paramilitary squads that have tried to assassinate him.

Goez is not unlike countless pastors, union leaders, and journalists. Each group has become mired in Colombia’s fierce ideological war. Leftist guerrillas, private armies, and right-wing paramilitaries—backed by factions within the Colombian army—have torn the country asunder since the 1960s.

The church in Colombia has paid a staggering price in this conflict. In 2004, armed groups murdered 40 Protestant leaders, according to the Council of Evangelical Churches of Colombia. More than 50 congregations closed due to violence. (Nearly 10 percent of Colombia’s 47 million people are Protestant.)

“All those funerals. So much death. In this war, the violence, the threats, the death, it penetrates your soul,” says Mennonite pastor Ricardo Esquivia, one of Colombia’s leading Protestants and peace activists. “So you pray, asking God for strength so that your soul does not become as sad as all the things happening around you.”

In 2005, New York’s Tanenbaum Center for Interreligious Understanding praised Esquivia’s efforts, honoring him with the prestigious 2005 Peacemaker in Action award.

Since the 1980s, more than 200,000 Colombians have died in the violence, and up to 3.4 million have fled their homes. Community leaders have been hit especially hard. More than 4,000 union leaders have been killed. The death toll includes 62 Roman Catholic priests, nuns, and missionaries. Four bishops have been kidnapped and one has been murdered. The Catholic archbishop of Cali was assassinated.

“What has happened to me is typical of the things that happen in Colombia,” says Goez, sitting in an austere apartment in a town that he asked not be identified. No one in this community knew him until he was transferred here to fill the empty pulpit of a congregation of the Presbyterian Church of Colombia.

“I’m not the only one who has faced this situation,” Goez says. “Many others have faced the same. When you do a job that helps people, others don’t always like that.”

Social Sin and Misery

A long time ago, Goez and other church leaders realized that charity alone would not provide a comprehensive solution for the 49 percent of Colombians living in chronic poverty.

Many complex factors contribute to poverty. Private armies have terrorized poor farmers off their land. The oil industry and agribusiness take possession of strategic land to explore for oil or to grow coffee, bananas, or flowers for the florist industry. As a result, millions more Colombians today live in urban areas, working in low-wage textile or food-processing jobs.

Many churches care for the poor through traditional outreach and human-rights advocacy. But there has been a backlash. According to reliable reports from displaced farmers and others, the government’s military intelligence has kept the Presbyterian Church of Colombia under surveillance for documenting human-rights abuses.

According to church leaders who asked not to be named, video surveillance tapes of the Presbyterian headquarters in Barranquilla were used during interrogations after a church worker, Mauricio Avilez, was arrested on suspicion of guerrilla activities. Allegations against him were later dropped.

Avilez is part of a corps of peace-minded lay workers who face the prospect of being killed and now live in hiding—just like their pastors. In August, Presbyterian Milton Mejia, the former executive secretary of the denomination, left Colombia on a study visa to the United States—but also to escape death threats. A staunch defender of human rights, Mejia’s life has been threatened multiple times.

Although Goez is in hiding, he has not given up on outreach to those who ask him hard questions. He told Christianity Today that chronically poor Christians ask their pastors questions like: “‘If God loves me, why do we live this way? Why are my children starving if God is good?”

“How do I explain to these people that God isn’t responsible for the fact that they have no good place to live, no food to eat?” he asks. “None of that is because of God. This suffering isn’t because of [their] personal sin, but a social sin that has immersed this country in misery.”

Since the 1960s, Colombia’s history has been a complex and bloody interplay of many forces. In 2006, President Alvaro Uribe was reelected to a second four-year term despite his mixed human-rights record. But under his administration (begun in 2002), murders, kidnappings, and massacres have decreased significantly. Uribe created a commission to oversee reparation and reconciliation and began demobilizing 31,000 paramilitaries. But the Latin America Working Group, a Washington-based advocacy coalition, says paramilitaries are getting light punishment, are not dismantling, and are threatening human-rights advocates.

In addition, there has been little progress toward a lasting peace. One major reason is that guerrillas, right-wing groups, and corrupt military units all benefit from the enormously profitable trade in illicit drugs—mostly cocaine and heroin. For years, the government, with U.S. help, has attempted to stop coca and poppy growing with aerial spraying of a potent herbicide, but to no avail.

Armed factions use their drug profits to fight each other as well as the government. Ordinary Colombians trapped in the deadly power struggle don’t stand a chance. Pastors who oppose such powerful forces often end up as traumatized as the people they are trying to help.

Firing Squads and Kidnappings

The Goez family is twice displaced. In 1999, Goez pastored a 300-member church in Saiza, a mountain parish on Colombia’s steamy north coast. One day, a paramilitary squadron rounded up 70 men, including Goez, and lined them up before a firing squad, in retaliation for an undisclosed offense.

Awaiting his fate in the lineup, Goez suddenly yelled, “Run!” Immediately, all scattered. Fifty-eight men survived, hiding in the hills, while paramilitary soldiers burned their village to the ground.

Then Goez moved to Cartagena, a northern port city that is home to thousands of other displaced families. When his tiny congregation extended help to the Nelson Mandela Camp—teaching the Bible and offering leadership training—Goez began receiving death threats.

In March 2005, unidentified thugs kidnapped, beat, and nearly drowned the pastor’s 15-year-old son, sending the boy home, finally, with a message for his father: “Your coffin is ready.”

The torture of his son was almost more than Goez could bear. The family left Cartagena, eventually regrouping in another town with only the clothes on their backs and a boatload of trauma.

Colombia’s pastors and their families draw strength not only from their faith but also from each other. Mennonite Esquivia, who earned his stripes working along Colombia’s violent north coast and dodging death threats for two decades, has become a key resource for other church leaders and peacemakers.

A negotiator by nature, Esquivia is among the few clergy in conversation with both Left and Right. In 1988, threats drove Esquivia, his wife, and his four children off their farm, losing everything but their lives. Nine years later, he moved to Bogotá and created a faith-based human-rights group called Justapaz (Just Peace), which is today a respected religious voice in Colombian political debate.

In 1993, he spent four months in exile in the United States and Canada. Death threats started again in 2004, when paramilitaries accused Esquivia of having direct ties to leftist guerrillas, a charge he has since refuted.

Colombian pastors have brought international attention to their situation. In U.S. congressional hearings, Esquivia and Presbyterian leader Mejia urged the U.S. government to redirect billions of federal dollars from military aid to development work, in order to help farmers switch from coca production to growing legitimate crops. Since 2000, the United States has granted $4.7 billion to assist in the war on drug trafficking. Experts say the funds have done little to alter the situation in Colombia.

Pastors believe that building new roads and bridges would help farmers ship produce from rural areas to urban markets. That view has gained credibility. “Uribe’s second term needs to provide new rural investment and infrastructure that reaches the poor,” an International Crisis Group briefing paper concluded in October. Also, outreach to rural areas receives support from the Presbyterian Peace Fellowship, which the Presbyterian Church USA supports. It regularly sends Americans to visit and encourage mission leaders and displaced farm workers.

The chronic stress on church congregations and pastors’ families poses a real threat to those who advocate for human rights.

Magdalena, the wife of pastor Goez, says she often is gripped by fear just walking along a public sidewalk. She watches for signs of being followed and pauses before turning corners. She is jumpy in the vicinity of motorcycles—a favorite vehicle of assassins who shoot and speed away.

Goez has pondered leaving the pastorate. He worries about the long-term effects of trauma on his family. To survive, he has tempered his methods, adopting more of a social-service strategy and meeting the everyday needs of his congregation and its neighborhood.

Outside his front door, scores of tipsy sheds line the roadways. These dwellings are full of squatter families afraid to return home, where the armed groups who forced them off their land are now in control.

Goez recites Paul’s words from 2 Corinthians 4 when fear grips him: “We are afflicted in every way, but not crushed … and so we do not lose heart.”

As the room darkens one evening and night settles in, Goez pauses in his conversation. He walks to the kitchen to remove the light bulb from the receptacle in the ceiling; he returns to the living room and screws it into an empty socket there. Light bulbs are scarce in his neighborhood.

Goez sits down and resumes his thoughts. “I’ve faced a lot of difficult times [and] understand the magnitude of the problems facing the Colombian people. I’ve been able to see the mercy of God in the deepest crises. When there is darkness, we have to believe in light.”

“And the proof of God’s mercy,” says Goez, “is that I am alive to tell this story.”

Alexa Smith is a journalist from Louisville, Kentucky, who has reported on Latin America for the last four years.

Copyright © 2007 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

Other stories on Colombia can be found on our website.

The BBC and the U.S. State Department have country profiles of Colombia.