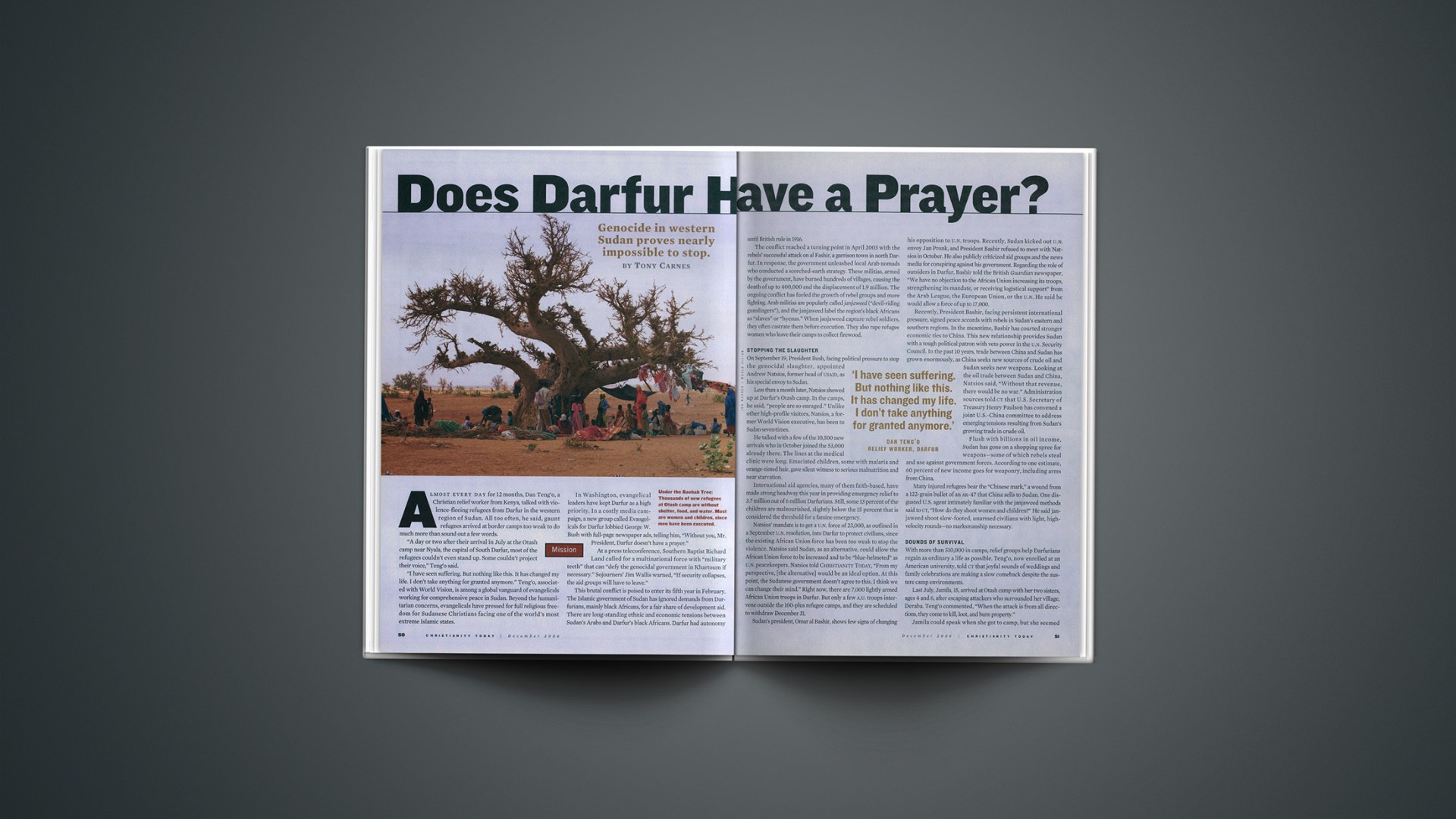

Almost every day for 12 months, Dan Teng’o, a Christian relief worker from Kenya, talked with violence-fleeing refugees from Darfur in the western region of Sudan. All too often, he said, gaunt refugees arrived at border camps too weak to do much more than sound out a few words.

“A day or two after their arrival in July at the Otash camp near Nyala, the capital of South Darfur, most of the refugees couldn’t even stand up. Some couldn’t project their voice,” Teng’o said.

“I have seen suffering. But nothing like this. It has changed my life. I don’t take anything for granted anymore.” Teng’o, associated with World Vision, is among a global vanguard of evangelicals working for comprehensive peace in Sudan. Beyond the humanitarian concerns, evangelicals have pressed for full religious freedom for Sudanese Christians facing one of the world’s most extreme Islamic states.

In Washington, evangelical leaders have kept Darfur as a high priority. In a costly media campaign, a new group called Evangelicals for Darfur lobbied George W. Bush with full-page newspaper ads, telling him, “Without you, Mr. President, Darfur doesn’t have a prayer.”

At a press teleconference, Southern Baptist Richard Land called for a multinational force with “military teeth” that can “defy the genocidal government in Khartoum if necessary.” Sojourners’ Jim Wallis warned, “If security collapses, the aid groups will have to leave.”

This brutal conflict is poised to enter its fifth year in February. The Islamic government of Sudan has ignored demands from Darfurians, mainly black Africans, for a fair share of development aid. There are long-standing ethnic and economic tensions between Sudan’s Arabs and Darfur’s black Africans. Darfur had autonomy until British rule in 1916.

The conflict reached a turning point in April 2003 with the rebels’ successful attack on al Fashir, a garrison town in north Darfur. In response, the government unleashed local Arab nomads who conducted a scorched-earth strategy. These militias, armed by the government, have burned hundreds of villages, causing the death of up to 400,000 and the displacement of 1.9 million. The ongoing conflict has fueled the growth of rebel groups and more fighting. Arab militias are popularly called janjaweed (“devil-riding gunslingers”), and the janjaweed label the region’s black Africans as “slaves” or “hyenas.” When janjaweed capture rebel soldiers, they often castrate them before execution. They also rape refugee women who leave their camps to collect firewood.

Stopping the Slaughter

On September 19, President Bush, facing political pressure to stop the genocidal slaughter, appointed Andrew Natsios, former head of usaid, as his special envoy to Sudan.

Less than a month later, Natsios showed up at Darfur’s Otash camp. In the camps, he said, “people are so enraged.” Unlike other high-profile visitors, Natsios, a former World Vision executive, has been to Sudan seven times.

He talked with a few of the 10,500 new arrivals who in October joined the 53,000 already there. The lines at the medical clinic were long. Emaciated children, some with malaria and orange-tinted hair, gave silent witness to serious malnutrition and near starvation.

International aid agencies, many of them faith-based, have made strong headway this year in providing emergency relief to 3.7 million out of 6 million Darfurians. Still, some 13 percent of the children are malnourished, slightly below the 15 percent that is considered the threshold for a famine emergency.

Natsios’ mandate is to get a U.N. force of 23,000, as outlined in a September U.N. resolution, into Darfur to protect civilians, since the existing African Union force has been too weak to stop the violence. Natsios said Sudan, as an alternative, could allow the African Union force to be increased and to be “blue-helmeted” as U.N. peacekeepers. Natsios told Christianity Today, “From my perspective, [the alternative] would be an ideal option. At this point, the Sudanese government doesn’t agree to this. I think we can change their mind.” Right now, there are 7,000 lightly armed African Union troops in Darfur. But only a few A.U. troops intervene outside the 100-plus refugee camps, and they are scheduled to withdraw December 31.

Sudan’s president, Omar al Bashir, shows few signs of changing his opposition to U.N. troops. Recently, Sudan kicked out U.N. envoy Jan Pronk, and President Bashir refused to meet with Natsios in October. He also publicly criticized aid groups and the news media for conspiring against his government. Regarding the role of outsiders in Darfur, Bashir told the British Guardian newspaper, “We have no objection to the African Union increasing its troops, strengthening its mandate, or receiving logistical support” from the Arab League, the European Union, or the U.N. He said he would allow a force of up to 17,000.

Recently, President Bashir, facing persistent international pressure, signed peace accords with rebels in Sudan’s eastern and southern regions. In the meantime, Bashir has courted stronger economic ties to China. This new relationship provides Sudan with a tough political patron with veto power in the U.N. Security Council. In the past 10 years, trade between China and Sudan has grown enormously, as China seeks new sources of crude oil and Sudan seeks new weapons. Looking at the oil trade between Sudan and China, Natsios said, “Without that revenue, there would be no war.” Administration sources told CT that U.S. Secretary of Treasury Henry Paulson has convened a joint U.S.-China committee to address emerging tensions resulting from Sudan’s growing trade in crude oil.

Flush with billions in oil income, Sudan has gone on a shopping spree for weapons—some of which rebels steal and use against government forces. According to one estimate, 60 percent of new income goes for weaponry, including arms from China.

Many injured refugees bear the “Chinese mark,” a wound from a 122-grain bullet of an AK-47 that China sells to Sudan. One disgusted U.S. agent intimately familiar with the janjaweed methods said to CT, “How do they shoot women and children?” He said janjaweed shoot slow-footed, unarmed civilians with light, high-velocity rounds—no marksmanship necessary.

Sounds of Survival

With more than 510,000 in camps, relief groups help Darfurians regain as ordinary a life as possible. Teng’o, now enrolled at an American university, told CT that joyful sounds of weddings and family celebrations are making a slow comeback despite the austere camp environments.

Last July, Jamila, 15, arrived at Otash camp with her two sisters, ages 4 and 6, after escaping attackers who surrounded her village, Deraba. Teng’o commented, “When the attack is from all directions, they come to kill, loot, and burn property.”

Jamila could speak when she got to camp, but she seemed confused and stared into space. Teng’o said, “Sometimes, she goes into deep thoughts. She stands quietly, motionless.”

Workers offered to teach her a skill—maybe making pasta. Darfurians love pasta, a dish left over from the Italian influence in East Africa. The trade in pasta will last as long as foreign relief workers, hungry for familiar food, remain to protect the camps. When asked what she really wanted last July, Jamila stayed silent until finally saying, “I want peace.”

Darfur has been likened to the American Wild West, African-style, with nomadic camel-riding herders. In South Darfur, farmers of different tribes fought with each other over boundaries and brides, and over matters of honor and water. A generation ago, the conflicts were mostly local, uniting Darfurians in a cultural interplay of honor lost, conflict, and honor regained. Darfurians would sing about a plentiful land with lions, giraffes, gazelle, and abundant waters.

Now, the lions and giraffes are all but gone. The janjaweed roam up and down the region shooting, raping, and burning. Honor is gone. Moral boundaries have been thrown out of kilter. Local conflicts, previously resolved through tribal mediation, have spun into a national conflagration of war, genocide, banditry, and racist politics.

Over time, migration has changed the ethnic makeup of Darfur. More black Africans have been trekking into Darfur, so that today they number up to 65 percent of all the people there. Arab nomads have fewer places to graze their herds of camels and cattle.

Religious differences also contribute to the tense climate. Most Darfurians practice Sufism, a mystical expression of Islam. But Sudan’s national leaders are Sunni Arab Muslims and are closely linked to the fundamentalist Muslim Brotherhood, a wellspring of terrorism in the Middle East. A few democratic Sudanese intellectuals charge that government forces use extreme Islamic propaganda laced with Arab racism to spur conflict in Darfur.

Sharing a Stake in Peace

Natsios, during a lengthy interview with CT, said his strategy for peace rests on establishing the benefits of peace for all parties with a stake in Darfur.

For example, African rebels are committed to fighting because they have lost land and livestock. Natsios said, “A huge amount of property has been looted from the African tribes. They don’t have banks in Darfur, but the people have their land and camels, which also have been taken from them. I would estimate that the tribes lost at least 2 million camels.”

The Sudanese government may need peace, too, after suffering several stunning military defeats this past summer. Natsios said he explained to Sudanese rulers that they’re not going to defeat the rebels. “They think there’s going to be a military solution. I think they’re terribly wrong.”

A peace settlement must also address environmental problems. “The Sahara Desert is moving south. So, in northern Darfur, if we don’t go [get] water, there isn’t going to be anybody else there but the Sahara Desert.” Natsios said that the U.S. government is urging both sides to make peace. “There is a lot of water underneath the sands of northern Darfur. The U.S. government is prepared to help. But we’ve got to have peace.”

While the diplomats talk, the sound of AK-47 gunfire and burning villages crackles across the African savannah. Young children wander through enormous border camps, searching for their parents, siblings, or any familiar face. One grandmother cares for 26 orphans.

This year, 12 humanitarian workers have been killed. Many of them were Sudanese nationals transporting food and water into the region.

In one of the camps that Teng’o visited, he found children taking solace in poetry.

Wala al-Sheikh, a young Sudanese, reflected on the refugees and his own plight:

I am a leader in silence by pain and misery, When I stop and think about my land, When they try to tell me there is no war, I’d like to send them to Darfur, To see the war with the hen for a shell of protein.

Tony Carnes is a CT senior writer.

Copyright © 2006 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

Christianity Today‘s special section on Darfur is available on our site.

SaveDarfur.Org has information on the situation and how to get involved.

BBC News and The Washington Post have coverage sections on the conflict in Sudan. BBC also has a timeline and Q&A section on Darfur.

World Vision’s site has the organization’s latest news from Darfur.

The latest news on Sudan can be found at Sudan.Net. Other recent articles include:

Annan calls for urgent action on Darfur | The UN secretary general, Kofi Annan, today urged an emergency session of the UN human rights council to take immediate action over atrocities in Darfur, Sudan. (The Guardian Unlimited)

Peacekeepers kill 3 refugees in Darfur | African Union peacekeepers killed three Darfur refugees during a demonstration, the first civilian deaths at the hands of the force and a sign of further deterioration in the conflict, a U.N. official said Monday. (Associated Press)

Darfur: Talking Tough and Carrying a Toothpick | Butty interview with Omar Ismael. (Voice of America News)

Darfur sinks deeper into misery | Hope is dwindling in Darfur. (The Toronto Star)

The rape of Darfur: a crime that is shaming the world | Children as young as eight are attacked by militiamen (The Independent)

Faith Leaders Join ‘Weekend of Prayer for Darfur’ | Christian leaders are joiniing other faith leaders this weekend in prayer for the ongoing genocide in the Darfur region of western Sudan.(The Christian Post)