Leviticus may seem like an odd Bible book to use in evangelism. But not in West Africa, where in April 2005 the first ten chapters were read to the Lobi—a people of subsistence farmers, animistic mask-makers, and poison-arrow warriors in Burkina Faso—in their own language.

Many in the listening crowd were struck by the similarities between the sacrifices mentioned in Leviticus and those of the Lobi religion. This infuriated the son of a Lobi priest, who forbade the reading to continue, because it is taboo to speak of Lobi religious practices in public. But another listener shouted, “Well, it means that we, too, are descendants of this High Priest. Aren’t we?”

Such comments gave the Lobi translators an open door to share the gospel. They also validated the growing trend among Bible translators to bring the Old Testament to more of the world’s nearly 7,000 language groups.

Something was Missing

Doming Lucasi, a native Balangao translator from the rice-terraced slopes of the northern Philippines, worked on the New Testament as a young man. He has now launched an OT translation project. In a culture that contains similarities to the Old Testament’s sacrificial and legal systems, he said, “Having the New Testament without the Old is like having a sword without the handle.”

The Old and New Testaments, separated by a chronological gap of about 400 years, have in modern times also developed a translation gap. Of the 2,400 language groups with portions of the Bible, roughly 1,115 have the New Testament. Only 426 have a full Bible, including the Old Testament.

Christians have long upheld the value and interconnectedness of both testaments, at least since Marcion’s denial of the Hebrew Scriptures was rejected as heresy in the second century. Yet the missionary translation boom of the 20th century largely ignored the Old Testament.

“The assumption was that the New Testament alone was adequate, because it held the gospel message and would be sufficient for evangelization,” said Ralph Hill, international translation coordinator for Wycliffe Bible Translators. The focus on evangelism over church growth, coupled with shortages of personnel and resources and the Old Testament’s sheer, intimidating size, created today’s gap between the testaments.

Take Papua New Guinea, for example, the world’s most linguistically diverse nation with more than 820 indigenous languages. A surge of translation work in recent decades has put the New Testament into nearly half of those languages. Yet the 13 New Testaments scheduled to be dedicated during this year or next outnumber the estimated total number of complete Bibles, 12.

“Effective evangelism among unreached people groups needs to start with Genesis,” said Don Pederson, director of field ministry for New Tribes Mission (NTM). “It’s through the story of God’s interactions with man that his character is fully understood and people understand their dilemma, that they need a Savior.”

NTM, which focuses on planting churches among the unreached, began each of its 120 current translation projects in Genesis, translating key OT passages en route to the Gospels. These “chronological” translations will provide a framework of salvation history that Pederson believes is crucial for successful evangelism.

NTM missionaries found that groups coming out of animism or polytheism with only the New Testament had deficient understandings of God and sin. “Churches were being planted, but something was missing,” said Pederson. “The gospel was being presented, but people did not seem to be understanding it.”

Missionaries explain that the stories of the Old Testament connect well with many people groups, who often share the ancient Israelites’ tribal lifestyle of sacrifices, patriarchy, and agriculturalism. Increasingly, translation projects in the world’s three areas with the most need—the Indo-Pacific, Central Africa, and Central Asia—begin with the Old Testament.

The Old Testament also connects powerfully with Muslims. “Muslims are already familiar with the characters of the Old Testament—Abraham, Jacob, and especially Joseph,” said Natalia Gorbunova of the Moscow-based Institute for Bible Translation. “In this way, the OT becomes a bridge into the New Testament.”

The institute, which seeks to bring the Bible to 130 non-Slavic language groups living in Russia and Central Asia, has 22 Old Testament projects, primarily for Muslims. A recent translation in Crimean Tatar, called “Prophets,” contains selections from Genesis, Exodus, and other OT books and tells the stories of biblical characters known in both Islam and Christianity, accompanied by relevant New Testament excerpts.

Although access to the New Testament has birthed many churches, translators say the Old Testament is needed to ensure churches’ long-term health and growth. “Since churches must go beyond evangelism, they need the whole picture and the whole Bible,” said Phil Towner, director of translation services for United Bible Societies. “It’s not just a matter of evangelism. It’s a matter of being in this Christian adventure for the long haul.”

Some translators attribute syncretism in Africa and other parts of the world to imbalanced and inadequate exposure to biblical truth. “For the sake of a long-term, growing church that is going to face problems of theology and practice,” said Wycliffe’s Hill, “they will want to consult the whole Bible.”

Today, translation experts estimate that about 500 of the 1,700 translations underway are full Bible projects. Most of the rest involve at least some parts of the Old Testament, often short, straightforward narratives like Esther, Ruth, and Jonah.

“We would not be involved in an Old Testament project except that the people say they want it,” said Walt DeMoss, director of program ministries for Lutheran Bible Translators. “They just develop a hunger for more of God’s Word.”

Some groups request specific Old Testament passages regarding the Creation, suffering, or other themes. But many express the same wish as Lama translators in Togo, who want the whole story simply so they can understand Jesus better.

“In many cultures, knowing someone’s background, someone’s grandfathers, is quite important to knowing them,” said DeMoss. “And where do you find these ‘grandfathers’ to know more about Jesus except in the Old Testament?”

Grassroots Translations

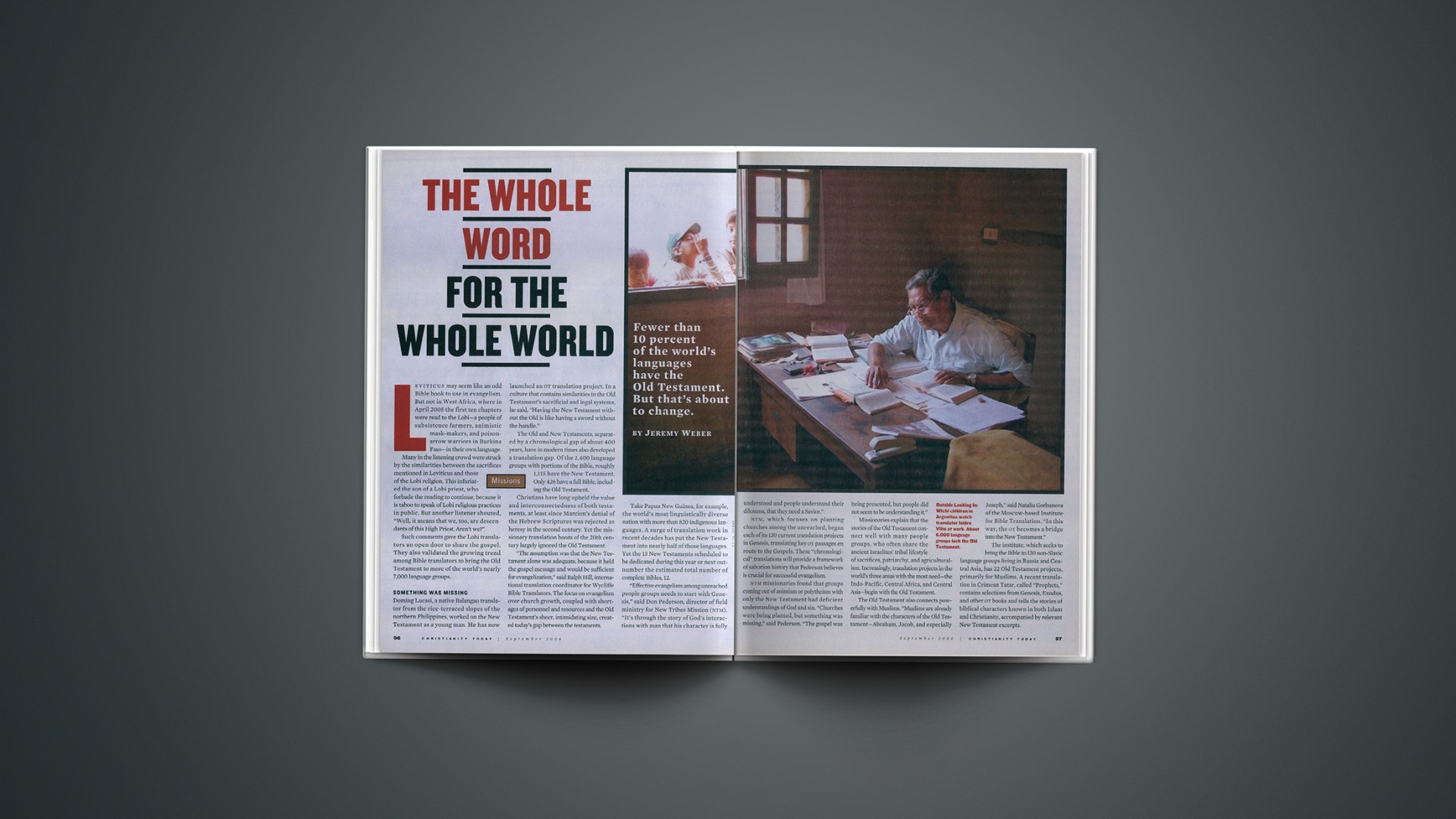

OT projects have become more feasible due to another movement: the increasingly central role of national translators. Nationals now compose 90 percent of the world’s translation force. They generally produce higher quality translations at a faster pace, because they know their own language and culture well. Many translation agencies have begun using Western missionaries primarily as quality-checkers and advisers—especially for comparing translations against the original Hebrew and Greek—while nationals do the actual translation work.

“The future of Bible translation in the world is in empowering and releasing nationals to do the work,” said Véroni Krüger of Word for the World, a whole-Bible translation group founded in South Africa. “I don’t see any other way in which we can complete the task.”

The ideal situation may be national translators who know Hebrew and Greek and are thus able to translate straight from the original biblical texts into their own languages. The time saved by this approach is often worth the additional training costs, DeMoss said.

However, only 10 percent of national translators have biblical language skills, as such training remains a luxury due to its expense or to the education level of translators. This number is growing slowly, as programs teaching biblical languages become increasingly available worldwide.

Wycliffe sponsors translation schools in the Philippines, Thailand, Kenya, and Cote d’Ivoire. Word for the World offers a mobile two-year program that in 2005 trained 175 translators from 73 language groups in Ethiopia, Tanzania, and other African countries.

Speed of learning and retention are better when learning Hebrew as a living language, according to Halvor Ronning, founder of the Jerusalem-based Home for Bible Translators. His program has provided advanced biblical language training to 74 translators from 26 countries speaking 44 different languages, and his students have gone on to lead translation efforts in Kenya, Togo, Nigeria, and other nations.

George MacDonald, a translator in Papua New Guinea, said he would always remember the day his Dadibi friends dedicated their complete Bible in 2001. Living in a remote location and considered inferior by trade partners, the Dadibi had long looked down upon themselves. Yet they became one of the few groups worldwide to receive both an Old and New Testament in their own language.

“This indicates that God has certainly not forgotten them, but instead has looked with favor on them,” said MacDonald.

Thousands turned out for the dedication ceremony—some walking for up to two days to get there. The national translators held the Dadibi Bibles up for the crowd to see. Thunderous applause arose, and one man let out a high-pitched yell reminiscent of the victory shout used by returning Dadibi warriors in days of old.

Jeremy Weber is a journalist and freelance writer living in Chicago.

Copyright © 2006 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

More CT articles on Bible translation include:

The Word from Geecheetown | Gullah-speaking slave descendants welcome New Testament translation. (Dec. 19, 2005)

Wycliffe in Overdrive | Freddy Boswell describes the most audacious Bible translation project ever. (Feb. 3, 2005)

God’s Own Dictionary | You won’t believe the words that didn’t exist until the first English translations of the Bible. (Feb. 05, 2003)

A Translation Fit For A King | In the beginning, the King James Version was an attempt to thwart liberty. In the end, it promoted liberty. (Oct. 22, 2001)

Not Your Grandfather’s Mission Field | From lighter radios to lightning-fast computers, technology is speeding up ministry and easing the load at Wycliffe Bible Translators. (Feb. 19, 2001)

Meaning-full Translations | The world’s most influential Bible translator, Eugene Nida, is weary of ‘word worship.’ (Sept. 16, 2002)

New Bible translations help to preserve world’s disappearing languages | The total number of languages in which the Bible is available in part or in its entirety now stands at 2233. But this is still barely more than one third of the estimated 6500 living languages in the world. (Feb. 28, 2000)

And the Word Was … Debatable | All those who take up the daunting task of Bible translation step into a force field of tension. (May 18, 1998)

‘Your Sins Shall Be White as Yucca’ (Part 1 of 3) | Wycliffe missionaries Gene and Marie Scott gave nearly 40 years of their lives translating the New Testament for a small tribe in the jungles of Peru. Was it worth it? (Oct. 27, 1997)

Confessions of a Bible Translator | In this article, Daniel Taylor, and English professor at Bethel College in Minnesota, gives us a glimpse into that most daring of undertakings—humans translating God’s Word. (Oct. 27, 1997)

More Bible articles are available on our website.