I had a chance on a recent trip to attend one of the most successful churches in America. It packs in more than 20,000 people at its weekend services. Its pastor is the author of bestselling books and is a world figure. The church is inspiring, effective, and relevant.

Fortunately, it became impossible to attend there, and instead I was blessed to end up at an irrelevant church. Our family arrived promptly at 10:00 A.M., and we were greeted by a woman who was getting up from pulling a few weeds in front of the church sign. She welcomed us warmly and escorted us into the nearly empty sanctuary. After we were greeted by two other people, as well as the pastor, a handful of people straggled in and worship began.

We were led in music by the weed-puller, who now had a guitar strapped on. She was accompanied by two singers and an overweight man on percussion. They were earnest musicians who, frankly, were sometimes flat or a little stiff, as if they were still trying to learn the music. The service, which included maybe 45 people, bumbled along—that is, by contemporary, professional, “seeker-sensitive” standards. The dress of the congregants suggested that there were some people of substance there, as well as some people on welfare. Some blacks, mostly whites. In front of me sat a woman wearing way too much makeup (at least according to my suburb’s refined standards), pouffy hair, and an all-black outfit.

JESUS MEANAND WILD:The UnexpectedLove of anUntamable Godby Mark GalliBaker Books192 pp.; $17.99 |

Communion was introduced without the words of institution—a bit of a scandal to my Anglican sensibilities. The pastor took prayer requests, and petitions were made for illnesses, depression, and a safe journey for my family.

It was during the announcements that I began to suspect I was in the midst of the people of God. The pastor sought more donations for the food closet, at which time he noted a new milestone: The church had served 22,000 people with groceries in ten years. Everyone applauded, then settled in to hear a clear and truthful sermon about God’s love for us despite our sin.

Afterwards, my family was warmly greeted by another five or six people, one of whom invited us to lunch. It was evident that they really didn’t care that we were not coming back. They just wanted to make sure we felt welcomed.

Nothing slick. No studied attempts to be authentic or relevant or cool. Just a small bunch of sinners, of all classes and races, looking to God for guidance and reaching out to the community in love.

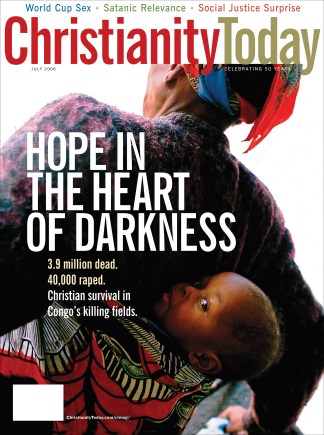

This little church will never make the list of the top ten churches in America. It will never be featured in Time or Newsweek or even Christianity Today. Its musicians will not go on to record a CD; its pastor will not be invited to national preaching conferences. The church will not likely grow into the thousands.

I’m sure that had I attended the megachurch, I would have been inspired by the music, moved by the message, impressed with the professionalism and efficiency of the service, and made to feel comfortable sitting next to people who dressed like me, an upper-middle class suburbanite.

But it was a more godly experience to go to that little fellowship, because I believe that for all the good megachurches do, this little fellowship manifested the presence of Jesus in a way that is unique and absolutely necessary in our age.

What Betrayal Actually Looks Like

From the beginning, Christians have been tempted to confuse success with faith. Peter was the first one to succumb to this confusion.

When Jesus told the disciples he would be killed, Peter was scandalized (Mark 8:31-33). He had imagined, I suppose (for the text doesn’t really say, though the larger context suggests it), that Jesus was moving from success to success. Jesus had started with a small band of 12, and lately he’d had up to 5,000 attending his little talks. He’d challenged the authorities of the day, but given his popularity, they had been unable to lay a hand on him. Peter likely imagined that when Jesus spoke about the coming kingdom, he was talking about politics, and Peter and the disciples would someday be cabinet members in his future administration. Power. Glory. Success.

Jesus knew very well that craving success and respectability was a temptation to his disciples, and he spent his whole ministry trying to disabuse them of it. He told those whom he’d healed not to tell anyone—an inept marketing decision if there ever was one. He warned bickering disciples that they should worry less about who would have authority in the coming kingdom and more about serving one another.

And he explained that his ministry, as “successful” as it appeared, would culminate in his death.

Peter would hear no such thing and rebuked Jesus, which provoked Jesus to “rebuke” him in turn. As is fitting, Jesus had the last word: “Get behind me, Satan!” He called Peter the incarnation of evil and then told him (in verse 35 about saving and losing life) to stop measuring success by human standards.

Since Peter is understandably confused—I mean, nearly everyone thought of the kingdom in political terms—Jesus seems cruel to chastise Peter as satanic. Not the most diplomatic approach in any circumstance. But apparently Jesus thought that Peter was not just guilty of misunderstanding, but also of betrayal.

No Slight Misunderstanding

Today, we know all too well that the kingdom of God is not a political entity (though many on the Left and Right are sorely tempted to think otherwise). But we still, like Peter, thirst for glory and power. We make much ado about our Christian superstars—bestselling authors and platinum-selling musicians and powerful preachers who draw people in by the tens of thousands. We not only admire, but we also lift up and reward such success. We too easily imagine that growing numbers are an infallible sign of faithfulness. We confuse righteousness with arithmetic.

Conservative churches, for example, often point out gloatingly how liberal churches are shrinking and conservative churches are growing. The usually unspoken assumption is that such growth signals God’s blessing.

But church growth is often nothing more than the product of good social science. Today, when someone wants to start a church, the first thing they do is study the people they are trying to reach and then craft worship and ministry to meet the needs of that target audience. That is, church founders do their best to appear acceptable and relevant to their target audience.

To minister to college-educated, upwardly mobile 20- and 30-somethings—target of a lot of new ministries these days (whatever happened to preaching to the poor and the prisoners?)—you forbid hymns and organs, and preach—no, make that “share”—sans pulpit, while wearing an Abercrombie & Fitch shirt, Dockers, and flip-flops.

And it works, because lots of churches that do this sort of thing are bursting at the seams with 20- and 30-somethings.

Donald Miller, a 30-something himself, talks about this in his book Blue Like Jazz. He has a pastor friend who started a new church. It was going to be different from the old church, Miller was assured: It would be relevant to the culture and the human struggle.

Miller notes, “If the supposed new church believes in trendy music and cool Web pages, then it is not relevant to culture either. It is just another tool of Satan to get people to be passionate about nothing.”

It is not an accident that Miller, like Jesus, uses the S-word to react to what is threatened here. To long for relevance, success, effectiveness, and glory—this is not just a slight misunderstanding of the gospel, but its very betrayal. It is not error. It is, according to Jesus, satanic.

Philosopher Søren Kierkegaard made a similar point when he riffed on Matthew 23, where Jesus speaks his harshest judgment on the religion of his day:

Woe to the person who smoothly, flirtatiously, commandingly, convincingly preaches some soft, sweet some thing which is supposed to be Christianity! Woe to the person who makes miracles reasonable. Woe to the person who betrays and breaks the mystery of faith, distorts it into public wisdom, because he takes away the possibility of offense! … Oh the time wasted in this enormous work of making Christianity so reasonable, and in trying to make it so relevant!

Merciful End to Dreams

Fortunately, embedded in the argument between Peter and Jesus is just the mercy we need. Jesus’ rebuke to Peter—and the implied rebuke to us today—is the most gracious thing he could have done. Sometimes, Jesus’ rebuke comes to us in words, but most of the time it comes in the warp and woof of Christian living.

The first church I served after seminary offered a traditional Presbyterian worship service. Old hymns, written prayers, formal and, to me, stiff throughout. I remember looking out over the congregation during one interminable Communion service, feeling sorry for the congregants as they had to endure this empty ritualism. During the service, I read the prayers the senior pastor had asked me to read, but in between, I imagined myself in my own church, how I would make worship really relevant to the culture!

After the service, one elderly woman approached me smiling broadly and pumped my hand in gratitude. “Thank you so much for helping with the service,” she bubbled forth. “It was one of the most meaningful Communions I have experienced in years.”

I was shocked, and it took a few weeks for her words to sink in. But sink in they did, as I informally conducted a survey of parishioners. To my surprise, most of them found our services moving and meaningful. I felt the rebuke of Jesus: “What is ‘relevant,’ ‘meaningful,’ and ‘powerful’ is more mysterious than you imagine.”

Like many young pastors, I was afflicted with an ungodly idealism. I believed that a church made in my image—an image I was convinced was formed only by the Bible and my deep theology and uncommon spirituality—was the church of God’s dreams. Theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer warned about such idealism in his now classic Life Together: “He who loves his dream of community more than the Christian community itself becomes a destroyer of the latter, even though his personal intentions may be ever so honest and earnest and sacrificial.”

The relevant community of faith we imagine is usually a combination of biblical and cultural and personal expectations, some of them so deeply embedded in our psyches that we assume their inherent righteousness. Because they are dreams, they usually have little to do with the reality called the church. When we try to fashion the church in our image, the result is often anger, division, and hostility. As young pastors, we chalk this up to the price of being prophetic leaders. But often it’s merely lust for ecclesial success. And we sometimes end up destroying the very community we came to save.

The reality of that community—the Christians really there, acting as they usually do—is a shocking disappointment to the dreamer. The church is indeed often boring and irrelevant. Its leaders bicker, its members gossip, and its building can be an embarrassment to modern sensibilities (aesthetic and environmental). The old charge remains true: The church is full of hypocrites. The typical church in history, the typical church today, has little to commend itself in the way of glory, power, and success.

And yet it is this institution—not our dream institution—that Christ identifies with. He has put his very name on it, calling it his body. He endorses it, seemingly without reservation, and tells us to draw people into this institution if they are to come to know him.

Along the way, Jesus works ever so hard to snap us out of our illusions. Bonhoeffer put it this way:

By sheer grace, God will not permit us to live even for a brief period in a dream world. He does not abandon us to those rapturous experiences and lofty moods that come over us like a dream. God is not a God of the emotions but the God of truth. Only that fellowship which faces such disillusionment, with all its unhappy and ugly aspects, begins to be what it should be in God’s sight, begins to grasp in faith the promise that is given to it.

What it should be in God’s sight is not glorious, powerful, and successful by our standards, but faithful. This means the church, and every member in it, must die to dreams of relevance and success. We have to let all that be crucified. It also means letting the church be the church, the flawed institution that God has used time and again to further his kingdom in the world.

We rightfully glory in the Reformation, the time when theologians like Martin Luther, John Calvin, and Thomas Cranmer led the church through a desperately needed reform. But we should remember that those theologians were nurtured in the “moribund” medieval church they eventually reformed. The Great Awakening was a wonderful time of church renewal in America and Britain. But the preachers who brought revival—George Whitefield, John and Charles Wesley, and others—were nurtured and raised in “dead” churches. Somewhere in that irrelevant environment, God worked in and through the church to renew them, and through them, the entire church.

Crucified Relevance

We are not wise to disparage successful megachurches, which often are catalysts for significant change in the church. What we should repudiate—like Jesus, in the strongest terms—is the notion that these churches represent the true church, the glorious church, the epitome of success.

To be sure, the church is in constant need of reform, during some eras more than others. So we need our reformers and, yes, visionaries, many of whom these days find their way into “successful” churches. But in every era, God raises up reformers within the very irrelevant, unsuccessful churches that need reform. “Relevance” and “power” and “success” are finally a mystery, not something that can be manipulated by church growth science, but something to pray for in humility and faith.

Jesus loves us so much, he sometimes slaps our vague idealism in the face with a healthy dose of reality. This shocks us, and we find ourselves speechless and blushing with either anger or shame. Not only do we not have the cool church we had hoped for, but we also don’t have an understanding Lord to comfort us through our faith crisis! Instead, Jesus rebukes us with reality and tells us to stop betraying his cause by worshipping the devil.

Like Peter, we have to die to our notions of relevance and success, and let God—through a crucified Savior, through an amateurish church, through a stiff Communion service—raise up his people when he will and how he will, with a power and glory we can hardly fathom.

Mark Galli is managing editor of Christianity Today. This chapter is excerpted from his latest book, Jesus Mean and Wild: The Unexpected Love of an Untamable God (Baker, 2006).

Copyright © 2006 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

Jesus Mean and Wild is available from Christianbook.com and other book retailers.

Publisher’s Weekly reviewed the book.

More information is available from Baker Books.

Other excerpts include:

Baptism + Fire | Suffering may build character, but ultimately it’s not about us. (Nov. 30, 2004)

The Angry Savior | Yes, Jesus taught peace and love. But Scripture reveals a Messiah who was not above losing His cool. (Today’s Christian, July/August 2006)

More CT articles warning against relevance include:

The Dick Staub Interview: Trusting in a Culturally Relevant Gospel | Os Guinness says that evangelicals have never strived for relevance in society as much as they do now. Ironically, he says, they have never been more irrelevant. (Aug 26, 2003)

Spirituality for All the Wrong Reasons | Eugene Peterson talks about lies and illusions that destroy the church. (March 4, 2005)

Resisting “Relevancy” | The church suffers when pastors confuse anecdotes with parables. (June 28, 2001)

A Cure for Spiritual Deafness | Relevance, we have surely mastered. What would happen if we sought a little irrelevance? (April 6, 1998)