In March of 1949, C. S. Lewis invited a friend named Roger Lancelyn Green to dinner at Magdalen College of Oxford University, where Lewis was a tutor. Green had attended Lewis’s lectures a decade earlier, and their friendship had grown over the years. It must have been especially refreshing for Lewis to contemplate an evening of food, wine, and conversation, for his life was miserable at that moment.

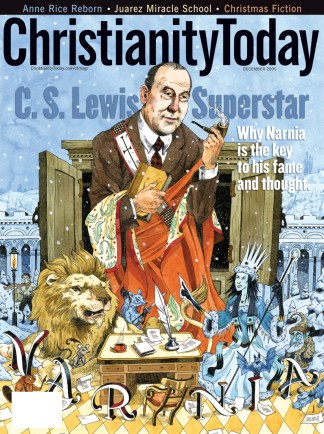

The Narnian:The Life and Imaginationof C. S. Lewis by Alan JacobsHarperSanFrancisco |

He lived with his brother and an elderly woman named Mrs. Moore, whom he often referred to as his mother—though she was not. Both of them were unwell and dependent upon him. Just a few days before his dinner with Green, Lewis had written to an American friend that he was “tied to an invalid,” which is what Mrs. Moore had become, confined to bed by arthritis and varicose veins. For her part, Mrs. Moore proclaimed that Lewis was “as good as an extra maid in the house,” and she certainly used him as a maid. She seems also to have become obsessive and quarrelsome in her latter years, worried always about her dog and constantly at odds with the domestic help.

Lewis hired two maids to help with cleaning and nursing when he had to be at Magdalen, where he maintained a grueling schedule of lectures, tutorials, and correspondence. But for a time, one of the maids became mentally unstable, and he occasionally had to return home to sort out conflicts the women had with each other and with Mrs. Moore. In 1947, he had been asked by the Marquess of Salisbury to participate in meetings, along with the archbishops of Canterbury and York, to discuss the future of the Church of England (of which Lewis was a member). He had declined: “My mother is old and infirm … and I never know when I can, even for a day, get away from my duties as a nurse and a domestic servant. (There are psychological as well as material difficulties in my house.)”

In the intervening two years, the miseries had if anything intensified. There are dark hints in some of his writings that the suffering shook Lewis’s Christian faith to the core. Though he had written of the joys of heaven, in the year of the Marquess’s letter, he found himself consumed by a “horror of nonentity, of annihilation”—that is, of finding that the God in whom he had trusted had no eternal life to offer.

Lewis was a famous man who would in a few months find himself on the cover of Time magazine and who was besieged by a blizzard of daily letters. He was determined to answer every correspondent, and his brother Warnie normally assisted him, primarily by typing dictated or drafted letters and keeping the files organized. But at the beginning of March 1949, Warnie was in Oxford’s Acland Hospital, having drunk himself into insensibility. After his release, Warnie wrote in his diary that his brother’s “kindness remains unabated,” but C. S. Lewis’s resources were failing. In early April, he wrote to a friend who had reproached him for not replying promptly to a letter, “Dog’s stools and human vomit have made my day today: one of those days when you feel at 11 a.m. that it really must be 3 p.m.” Two months later, he collapsed at his home and had to be taken to the hospital. He was diagnosed with strep throat, but his deeper complaint was simply exhaustion.

The Perfect Distraction

Such was C. S. Lewis’s world the evening he had Roger Lancelyn Green to dinner. It’s unlikely that Green had any idea how miserable his friend had been. Lewis was a charming host, and, as Green wrote in his diary, they had “wonderful talk until midnight: He read me two chapters of a book for children he is writing—very good, indeed, though a trifle self-conscious.” The book would become The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, the first story about a world called Narnia.

What is remarkable is that in the midst of all his miseries, Lewis turned to the writing of a story for children. He was already famous, but his fame was chiefly that of a polemical contender for Christianity. Certainly that was the thrust of Time‘s cover story on Lewis, which emphasized his then-forthcoming book arguing for the validity of belief in miracles. He was also a highly accomplished scholar, perhaps already (in his mid-40s) the most proficient among Oxford’s English faculty. He had written fiction, too, but of a highly intellectual character. The bachelor with no children of his own, and with relatively few friends whose children he knew, did not seem a likely author of a children’s book.

In the year before his death, Lewis told a correspondent, “My knowledge of children’s literature is really very limited. … My own range is about exhausted by MacDonald, Tolkien, E. Nesbit, and Kenneth Grahame.” He hadn’t even read The Wind in the Willows or Nesbit’s stories until he was in his 20s. Yet he never outgrew his love of the children’s stories he did know. Once he discovered The Wind in the Willows, it was forever precious to him. (He told a friend that he always read Grahame’s masterpiece when he was in bed with the flu.)

Moreover, Lewis served almost as a midwife to many children’s stories of his friends. In 1932, Tolkien took the chance of reading aloud to Lewis a story he had written. Lewis badgered Tolkien into seeking to have it published, which eventually he did in 1938: The story was called The Hobbit. So those who knew Lewis best weren’t surprised when he produced drafts of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe or when he published it in 1950. Perhaps they would have been surprised had they known that the story, and the six Narnia books that followed it, would bring him greater fame and influence than all his other books combined, making his name known around the world. The Chronicles of Narnia have been translated into more than 30 languages and, worldwide, have sold more than 85 million copies.

Though Lewis was a man who valued friendship above almost all else, such fame made him deeply uncomfortable. He had been a solitary child and always loved being alone. “I am a product,” he wrote, “of long corridors, empty sunlit rooms, upstairs indoor silences, attics explored in solitude, distant noises of gurgling cisterns and pipes, and the noise of wind under the tiles. Also, of endless books.”

In the books that peopled his solitude, Lewis discovered a range of interests (“nonsense, poetry, theology, metaphysics”) that, nurtured and matured, nearly all found their way into his career as a writer. The books by Lewis that Macmillan published in 1943 and 1944 alone (some had been written several years earlier) included two science fiction novels, a theological treatise about suffering, a satire in the form of letters from a devil, and two brief works in explanation and defense of the Christian faith. Looking at such variety, we can understand why Owen Barfield once wrote an essay about his famous friend called “The Five C. S. Lewises.”

Yet the chief point of Barfield’s essay is that what’s remarkable about Lewis is not the diversity of his writing, but the unity: the sense that something ties them all together. What is this unity? Barfield’s attempt to explain it is intriguing:

“There was something in the whole quality and structure of his thinking, something for which the best label I can find is ‘presence of mind.’ … Somehow what he thought about everything was secretly present in what he said about anything.”

So, what, specifically, was present to his mind?

Pictures in His Head

I want to suggest that Lewis’s willingness to be enchanted held together the various strands of his life: his delight in laughter, his willingness to accept a world made by a good and loving God, and his willingness to submit to the charms of a wonderful story. What is “secretly present in what he said about anything” is an openness to delight, to the sense that there’s more to the world than meets the jaundiced eye, to the possibility that anything could happen to someone who’s ready to meet anything.

For someone with eyes to see and the courage to explore, even an old wardrobe full of musty coats could become the doorway to another world.

After all the Narnia books were done, Lewis wrote an essay in which he explained that the stories began when he started “seeing pictures in [his] head”—or rather, when he started paying attention to pictures he had been seeing all along, since the “picture of a Faun carrying an umbrella and parcels in a snowy wood,” which we find near the beginning of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, first entered his head when he was 16 years old. It was only when he was about 40 that he said to himself, “Let’s try to make a story about it.”

As we have seen, it was a particularly trying time in his life when he wrote the first Narnia tale. Yet something—some instinctively strong response to the offer of enchantment, perhaps made all the more strong because of his difficult circumstances—made him start writing, even though he “had very little idea how the story would go.”

What made him write this way, and why it is such a good thing that he did—these are hard topics to talk about without seeming sentimental. Yet they are necessary topics. In most children, but in relatively few adults, we see a willingness to be delighted to the point of self-abandonment. This free and full gift of oneself to a story is what produces the state of enchantment. Why do we lose the ability to give ourselves in this way? Perhaps adolescence introduces the fear of being deceived, the fear of being caught believing in what others have ceased to believe. To be naive, to be gullible—these are the great humiliations of adolescence.

Lewis never seems to have been fully possessed by this fear, though he felt it at times. “When I was 10, I read fairy stories in secret and would have been ashamed if I had been found doing so. Now that I am 50, I read them openly. When I became a man, I put away childish things, including the fear of childishness and the desire to be very grown up.”

It was Richard Wagner’s vast landscapes of heroic myth that captured Lewis above all, and the gentler “Faerie” world of the English imagination, from Spenser to Tennyson, William Morris, and George MacDonald. He once wrote that stories which sounded “the horns of Elfland” constituted “that kind of literature to which my allegiance was given the moment I could choose books for myself.” It was perhaps inevitable that he would become a scholar of medieval and Renaissance literature, and that his first work of fiction would be an elaborate allegory based on Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress. He consumed works of fantasy and then science fiction (in which genre he would write his first novels). It was not likely that such an open mind would remain an atheist long, though Lewis did hold out as an unbeliever until nearly 30.

Wide Open to Glory

Lewis remained, in this particular sense, childlike, that is, able to receive pleasure from the kinds of stories that tend to give pleasure to children. Ruth Pitter, a poet and close friend of Lewis’s, wrote, “His whole life was oriented and motivated by an almost uniquely persisting child’s sense of glory and of nightmare. The adult events were received into a medium as pliable as wax, wide open to the glory and equally vulnerable, with a man’s strength to feel it all, and a great scholar’s and writer’s skills to express and interpret.”

Surely Lewis would have said that when we can no longer be “wide open to the glory,” we have lost not just our childlikeness, but also something near the core of our humanity. Those who will never be fooled can never be delighted, because without self-forgetfulness there can be no delight, and this is a great and grievous loss.

Often, when we talk about receptiveness to stories, we contrast an imaginative mindset to one governed by reason. We talk about freeing ourselves from the shackles of the rational mind. But no belief was more central to Lewis than the conviction that it is eminently and fully rational to be responsive to the enchanting power of stories. Lewis passionately believed that education is not about providing information so much as it is about cultivating habits of the heart—producing “men with chests,” as he puts it, people who not only think as they should, but also respond as they should, instinctively and emotionally, to the challenges and blessings the world offers them.

Lewis noted in the dedication of his book A Preface to Paradise Lost that “when the old poets made some virtue their theme, they were not teaching but adoring, and that what we take for the didactic is often the enchanted.” It is the merger of the moral and the imaginative—the vision of virtue itself as adorable, even ravishing—that makes Lewis so distinctive.

He achieves this merger most perfectly in his children’s books. He was quite aware of the restraints imposed on a person writing for children: “Writing ‘juveniles’ certainly modified my habits of composition. Thus: (a) It imposed a strict limit on vocabulary. (b) Excluded erotic love. (c) Cut down reflective and analytical passages. (d) Led me to produce chapters of nearly equal length for convenience in reading aloud.” But “all these restrictions did me great good—like writing in a strict meter.”

Writing for children also forced Lewis to concentrate on what was most essential—in the story, yes, but also in his own experience. In writing these tales for children, he found the bedrock of his own imagination and belief.

In 1954, Lewis responded to an invitation of the Milton Society of America to honor him for his contribution to the study of John Milton’s poetry. They asked him to “make a statement” about his published works, and he insisted that through them all “there is a guiding thread.”

The imaginative man in me is older, more continuously operative, and in that sense more basic than either the religious writer or the critic. It was he who made me first attempt (with little success) to be a poet. It was he who, in response to the poetry of others, made me a critic, and in defense of that response, sometimes a critical controversialist. It was he who, after my conversion, led me to embody my religious belief in symbolic or mythopoetic forms ranging from Screwtape to a kind of theologized science fiction. And it was, of course, he who has brought me, in the last few years, to write the series of Narnian stories for children; not asking what children want and then endeavoring to adapt myself (this was not needed), but because the fairytale was the genre best fitted for what I wanted to say.

Lewis was honored by the approval of the Miltonists, but he had to admit that he wasn’t really one of them. He was not one for whom scholarship was an end in itself. At the heart of his impulse to write—even to write scholarly works of literary criticism—was his warm and passionate response to literature as an “imaginative man.”

Lewis could make Narnia because the essential traits of Narnia were in his mind long before he wrote the first words of the Chronicles. He was a Narnian long before he knew what name to give the country. It was his true homeland, the native ground to which he hoped, one day, to return.

At the darkest moment in the first Narnia tale, when Aslan’s tortured and humiliated body lies dead on the Stone Table, Lewis writes: “I hope no one who reads this book has been quite as miserable as Susan and Lucy were that night, but if you have been—if you’ve been up all night and cried till you have no more tears left in you—you will know that there comes in the end a sort of quietness. You feel as if nothing was ever going to happen again.”

Only one whose misery had taken him to such devastated “quietness” could write these sentences. Lewis had known misery as a child; he knew it again as a middle-aged man. Yet it was out of this misery that a story for children came—at first a bumbling story, flat and uninspired, but one that Lewis couldn’t ignore.

As he wrote after all the Narnia stories were done, it was only when the great lion Aslan “came bounding into it” that he stopped bumbling and the story began to move in its proper course: “He pulled the whole story together, and soon he pulled the six other Narnian stories in after him.”

Into Narnia he also pulled Lewis, and then us.

Alan Jacobs is a professor of English at Wheaton College and author of The Narnian: The Life and Imagination of C. S. Lewis (HarperSanFrancisco, 2005), from which this article is condensed.

Copyright © 2005 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

CT’s full coverage of C.S. Lewis is collected on our site. CTMovies has a collection of articles about the film The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe.

Reviews of Alan Jacob’s books include:

Unfashionably Good | A savory collections of essays by Alan Jacobs. (Dec. 1, 2004)

Reading, Writing, and Charity | A theology of reading. (July 1, 2002)

Articles by Alan Jacobs from Books & Culture include:

Whose Natural Theology? | With the Grain of the Universe: The Church’s Witness and Natural Theology (November 1, 2003)

Wole Soyinka’s Outrage | The divided soul of Nigeria’s Nobel laureate. (November 1, 2001)

The Virtues of Resistance | Computer Control, part 3 (September 1, 2002)

Life Among the Cyber-Amish | Computer Control, Part 2 (July 1, 2002)

Computer Control | Who’s in charge? (May 1, 2002)

Shame the Devil | In the wake of September 11, everyone was quoting W.H Auden’s September 1, 1939. But Auden himself repudiated the poem’s most famous lines. (March 1, 2002)

It Ain’t Me, Babe | Bob Dylan, reluctant prophet. (May 1, 1998)

The Lord of Limit | Is Geoffrey Hill the greatest living English poet? (May 1, 2004)

The Editor and the Exile | How the New Yorker’s William Shawn gave a home to the brilliant autobiographer Ved Mehta. (November 1, 1998)