"How can you worship a homeless Man on Sunday and ignore one on Monday?" said the sign outside St. Edward's Cathedral in Philadelphia. Inside, a group of 40 homeless families were joined by students from Eastern University to protest the eviction of women and their children from the abandoned Kensington neighborhood church. In 1996, the story was all over the news as a community activist group and a crowd of Eastern students fought the eviction by living in the church, sleeping on pews, and worshiping each Sunday. Shane Claiborne and other students left Eastern's campus in St. Davids, drove the 20 miles into Philly, and unpacked their things in the nave.

At first, it was a shock to live among the homeless, Claiborne says. But face to face with poverty, stereotypes quickly broke down. During those fall days, as the stone building grew colder each night, the students began to rethink Gospel passages about the poor being blessed and doing "unto the least of these."

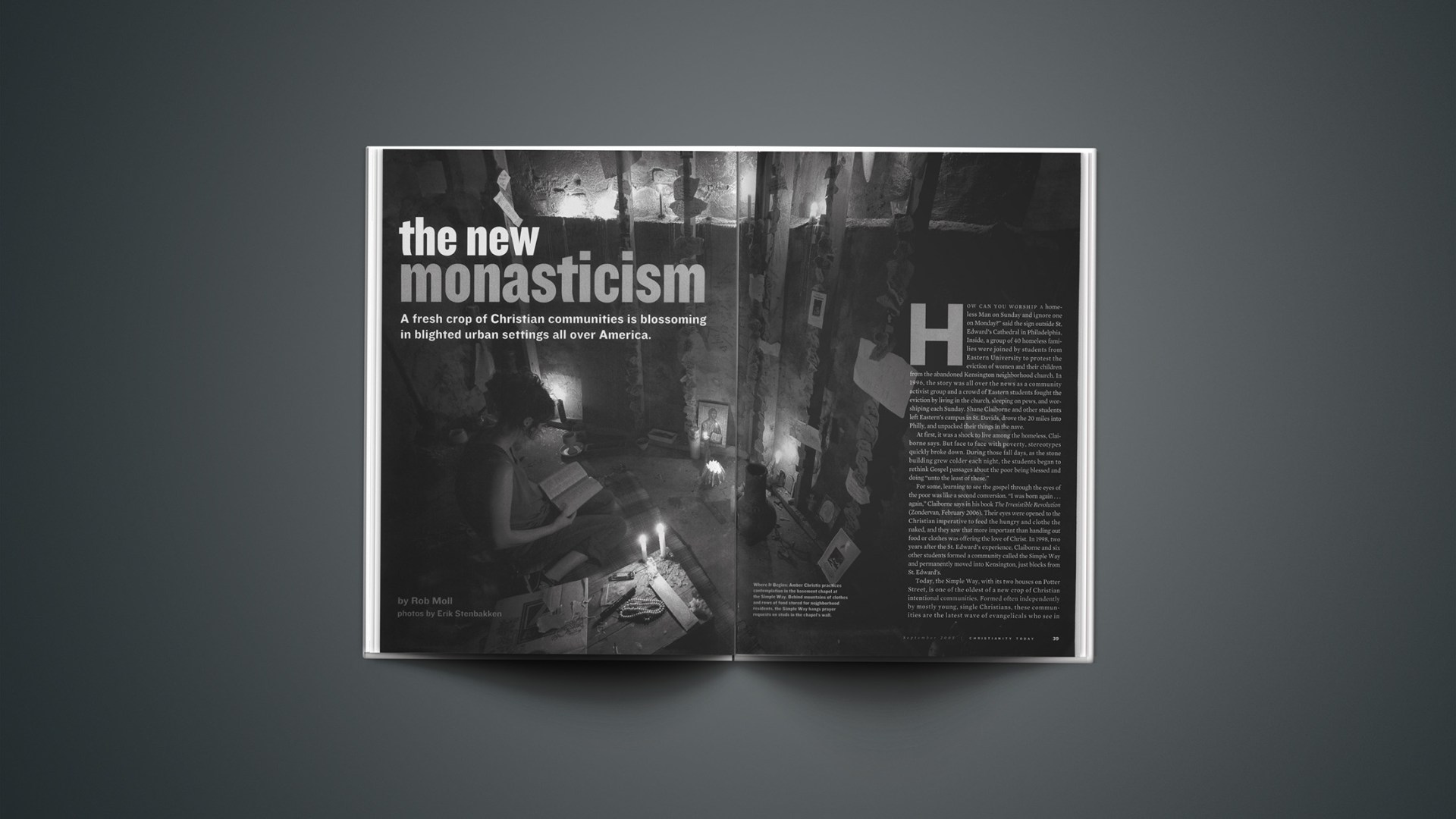

For some, learning to see the gospel through the eyes of the poor was like a second conversion. "I was born again … again," Claiborne says in his book The Irresistible Revolution (Zondervan, February 2006). Their eyes were opened to the Christian imperative to feed the hungry and clothe the naked, and they saw that more important than handing out food or clothes was offering the love of Christ. In 1998, two years after the St. Edward's experience, Claiborne and six other students formed a community called the Simple Way and permanently moved into Kensington, just blocks from St. Edward's.

Today, the Simple Way, with its two houses on Potter Street, is one of the oldest of a new crop of Christian intentional communities. Formed often independently by mostly young, single Christians, these communities are the latest wave of evangelicals who see in community life an answer to society's materialism and the church's complacency toward it. Rather than enjoy the benefits of middle-class life, these suburban evangelicals choose to move in with the poor. Though many of the same forces drive them as did earlier generations—a desire to experience intense community and to challenge contented evangelicalism—they are turning to an ancient tradition to provide the spiritual sustenance for their ministries.

'New Friars'

Scott Bessenecker, director of global projects for InterVarsity Christian Fellowship, says he sees among these evangelicals the latest burst in missionizing monastic orders. In his work among InterVarsity students, Bessenecker finds "an emerging movement of youth taking up residence in slum communities in the same spirit that I find in the start of the Franciscans and the early Celtic orders, in the Nestorian mission, and in the Jesuits."

Bessenecker is working on a book about these "new friars," as he calls them. There's a similar spirit among communities like the Simple Way, who call their movement the "new monasticism." Like earlier movements, the ones today attract mostly 20-somethings who long for community, intimacy with Jesus, and to love those on the margins of society. And they are willing to give up the privileges to which they were born.

A June 2004 conference officially marks the birth of the new monasticism, and participants wrote a voluntary rule for the many and diverse communities. New communities and academics met in Durham, North Carolina, with older communities like the Mennonite Reba Place Fellowship, Bruderhof, and the Catholic Worker. Drawing from church tradition and borrowing the term new monasticism from Jonathan R. Wilson's book Living Faithfully in a Fragmented World (Morehouse, 1998), participants developed 12 distinctives that would mark these communities, including: submission to the larger church, living with the poor and outcast, living near community members, hospitality, nurturing a common community life and a shared economy, peacemaking, reconciliation, care for creation, celibacy or monogamous marriage, formation of new members along the lines of the old novitiate, and contemplation.

These marks connect like-minded communities, new and older, to each other. They also provide a discipline and structure some observers say communities a generation ago lacked. "The marks show the common threads that connect Christian communities that might otherwise be seen as scattered anomalies, rather than vibrant cells of a body," says Claiborne, who is becoming a spokesman for the movement. "There are literally dozens of communities that I could consider a part of the new monasticism." The Simple Way's annual family reunion has served as a gathering place for many new monastic communities, and for several years running, more than 100 people meet for worship and to discuss community life and social justice issues.

Despite a growing interest, the conference was a surprise kickoff. Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove, a graduate student at Duke Divinity School and conference organizer, initially invited 10 practitioners and 10 academics, but word spread and in the end 60 attended. It was overrun by newer communities, says David Janzen, who participated in the conference and has lived at Reba Place since 1984.

Janzen, Wilson, Chris Rice, Norman Wirzba, and other members of older communities offered guidance on the 12 marks: Rice on racial reconciliation, Wirzba on environmentalism, and Janzen on forming novitiates, for example. About 14 newer communities attended, traveling from across the United States, including Iowa, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Oregon, Washington, California, Kentucky, Georgia, and Washington D.C. The conference culminated in a book, Schools for Conversion: 12 Marks of a New Monasticism, which introduces the movement. I had an opportunity to visit three of these communities, whose differences and similarities reveal the movement's core commitments.

Ancient-Future Activism

Kensington was once one of the most productive areas in America. It is home to hundreds of factories and thousands of row houses built a century ago for the workers. Residents used to say that job hunters walking down "factory row" on American Avenue would have a job by the time they reached the end. Huge stone churches, including St. Edward's, testify to a once-prosperous community. But over the last 30 years, the neighborhood lost more than 250,000 jobs as factories moved overseas, became automated, or simply went out of business. Families moved too, leaving 25,000 abandoned homes. Today it is Pennsylvania's poorest neighborhood. All the manufacturing is gone, leaving 700 crumbling, empty brick factories—often home to the replacement economy of prostitution and drugs, and sometimes, like abandoned churches, shelters for families with no better place to stay.

Despite Kensington's blight, the Simple Way has put down roots in the neighborhood, allowing members to intimately know the needs of residents and work on their behalf. For years, Claiborne says, the Simple Way tried to get the city to condemn an abandoned home at the end of their street, which had become home to drug dealers, users, and prostitutes. "It was unacceptable," Claiborne says. They petitioned the city to condemn the building and allow the Simple Way, which is registered as a nonprofit organization, to buy and rehab it. The city said it would cost $30,000 to buy it and take two years to process the paperwork.

But they weren't going to let red tape slow them down. While they worked with the city to gain ownership of the building, Simple Way members walked across the rooftops down Potter Street and entered the house through the roof. Inside, they found trash piled to the ceiling, walls and floors caving in, drug paraphernalia, and pornography. They cleaned it out, room by room.

Before their cleanup efforts made much progress, two people were murdered on the corner. The story made the evening news, and the local alderman, feeling pressure, promised to do something. The building was immediately condemned, canceling $150,000 in liens, and the house put up for auction. The Simple Way bought it for $14,000, and three days after gaining ownership, the building was clean.

Now with two buildings on Potter Street, the Simple Way is adding more, as the story of Adrienne Harbison, a single mother with two children, illustrates. She fled an abusive relationship and came to live with the community. The man she hoped to marry had beaten her so badly while she was pregnant with twins that he killed one of them. She took her oldest child, fled to a shelter, and tried to gain full custody. But she was told she couldn't have custody without a permanent place to stay. A nurse, Harbison couldn't work due to complications with her pregnancy, but at the shelter she heard about the Simple Way. Now Adrian and her two children, Bianca and Brandon, live in the once-abandoned building owned by the Simple Way, where she hosts a cell group from Circle of Hope, the church Simple Way members attend. The community is now helping Harbison to buy her own house around the corner. House by house, the Simple Way is making an impact.

Community members all work part-time jobs with a portion of their income going to the community to pay for living expenses. Though community life is not strictly regulated, they devote their spare time to personal Bible study and prayer, Simple Way activities, or local ministries, like helping neighborhood children with their homework or simply playing with them.

The Simple Way does not hesitate to advocate publicly for the poor. When Philadelphia officials began passing anti-homelessness laws, making it illegal to give food to the homeless, sleep outdoors, or ask for money, the Simple Way and other Christian community organizations protested in Love Park—a historic location and frequent hangout of homeless. They slept in the park alongside the homeless, held worship services, sang, prayed, and served Communion—in the form of pizza. When the media showed up with cameras and notebooks, the police were unwilling to enforce the new laws immediately—though Claiborne and others were eventually arrested.

Having spent time with Mother Teresa's Missionaries of Charity, Claiborne loves to say that the Simple Way does small things with great love, rather than doing simply great things. But when their protests ended with a court overturning the anti-homelessness laws, the Simple Way achieved both. When Claiborne and others appeared in court, Claiborne wore a T-shirt saying "Jesus was homeless." Claiborne says in his book that an intrigued judge asked him about it.

"Jesus says that the foxes have holes and birds have nests but the Son of Man has no place to lay his head," Claiborne told the judge.

"You guys might have a chance," the judge responded.

After hearing the case, the judge promptly found the group not guilty. She also asked Claiborne for one of his T-shirts.

Willow's Environmentalist Disciple

Across the Delaware River from Philadelphia in Camden, New Jersey, Chris and Cassie Haw, along with friends, moved into a house owned by Sacred Heart Catholic Church. Chris had heard the church's priest, Father Michael Doyle, talk about the environmental and social problems in Camden. It was not long after 9/11, and Chris knew he wanted to make a difference at the household level "right here in the U.S." He decided to move to Camden, called America's most dangerous city—and one of the most polluted.

Haw's concern for the environment began when he was a high-school student in Crystal Lake, Illinois. At Willow Creek Community Church, Chris first learned about social injustice. A group of interns, one of whom was Claiborne, "started asking questions about our way of life as contrasted with the call of the kingdom. I was taught about sweatshops, injustices, homeless people, mercy to the outsider, and other things unfamiliar to me." Haw learned to be a disciple of Jesus. "Willow Creek taught me that 90 percent discipleship is 10 percent short of full devotion," he says. "I took them at their word and set out to work through giving all."

Haw, his soon-to-be wife Cassie, and a group of friends formed the Camden House in 2003 in a house provided by Father Doyle. Though they didn't come to start programs, they have begun a few. Camden has plenty of resources offered by suburban churches, Cassie says, but the prostitutes and addicts who hang out across the street from their house need loving neighbors more than clothes.

In Camden, loving neighbors means advocating for basic needs, such as clean air. Unlike Kensington, the factories here still operate, but they've been modernized and don't employ many people. They spew so many toxins on the neighborhood that when Chris, a schoolteacher at Sacred Heart's Catholic school, takes his students outside for gym class, children sometimes throw up. Three superfund sites (particularly bad environmental disaster areas) are here in Camden, fenced off with warning signs. The town literally stinks of pollution, processed bacon, and diesel exhaust. So many families have fled that only half the houses are occupied. Entire blocks look bombed out, with doors and windows missing and roofs caving in.

The Camden House has been appealing to local industries to modify their pollution levels. Though their efforts have not changed businesses' habits, they have been given grants to start a greenhouse and gardens. The gardens, Haw says, are a way to reconnect residents to creation, which has been so badly damaged. They sell the fruits and vegetables to residents.

House members are free to work full time outside the house, though many work at the Catholic school across the street. All but one member (who was raised Catholic) grew up in evangelical homes. Another member, a therapist, spends most days out of Camden, but Haw says he earns more money than others, which allows the house more financial flexibility with its modified common purse. They have even been able to help one of their few neighbors pay off mounting debts, as well as seed gardens and start pottery and candle businesses.

The house quickly learned that allowing anyone interested in community living to move in can cause problems. They're also trying to learn how to form novices in community, and spiritual, life. They host interns and require new participants to stay for extended periods before becoming members. They discuss how new members will fit into the community and how God may be directing them to such a lifestyle.

For Tatiana Heflin, spending three weeks at the Camden House allowed her to explore community life. She interned at Reba Place last summer while a student at North Park University in Chicago. As someone interested in intentional communities and social justice, Heflin is also learning the difficulties and particular blessings of community life.

"I choose this life. I choose following Jesus, living counter-culturally, seeking the kingdom of God," she says. "Following Jesus is not promised to be wild and crazy, but a daily surrender and a taking up of my cross."

Looking at an old, abandoned factory, Haw says he's tempted to try to turn it into a church. It's the Willow Creek in him. But big programs are only tempting on occasion. Haw and others in the Camden House are more interested in living an environmentally sustainable life as a household protest to the pollution they daily breathe. They are all vegetarians, eating their homegrown foods and shopping carefully. Haw says he's unsure if the Camden House will last long term, but he knows living here, right now, is where God wants him.

Born Again in Babylon

"For many people, the new monasticism is like a second conversion," says Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove. "Before, the gospel was about Jesus taking away my sin, but the gospel is a new way of life." For Claiborne, it took place at St. Edward's; for Chris Haw, it began at Willow Creek and culminated when Father Doyle gave him the keys to the Camden House. Wilson-Hartgrove and his wife, Leah, were born again in Iraq.

At the start of the war, they traveled with Christian Peacemaker Teams to witness the effect of the shock-and-awe bombing campaign. Only days after the team entered Iraq, however, soldiers ordered them to leave. Outside the town of Rutba, between Baghdad and the Jordanian border, bomb shrapnel hit one of the vehicles in their caravan. Iraqis rushed to care for the five wounded passengers and took them to a nearby hospital, while their car lay in a ditch. The doctor explained that the hospital had recently been bombed, but said he would be able to help their friends. "Just tell people what's happening in Rutba," he said.

Jonathan has told the story in his book To Baghdad and Beyond (Wipf and Stock, 2005). Now in an all-black neighborhood called Walltown in Durham, North Carolina, the couple hopes to recreate the hospitality they received. Only a few blocks from the Duke University campus, Walltown was where the servants of Duke's faculty once lived. Tensions between residents and the university still run high. When the university built a housing development in the once-vacant lot between Walltown and the campus, Walltown residents saw it as the university's attempt to wall off Walltown from the campus. Here Jonathan and Leah are practicing racial reconciliation in a community they have named after their Iraq experience: Rutba House.

A grad student at Duke, Jonathan's first outreach began as an intern at St. John's Missionary Baptist Church located in Walltown. Sylvia Hayes, community outreach director at St. John's, says, "The community had a need for what he was doing. Not only has he worked with the community, he's worked [at the church] with the seniors, with the youth; he worked with people needing help finding jobs."

Though Jonathan and Leah plugged right in, they faced several obstacles as they tried to start a reconciliation community. Their first apartment was not in Walltown, so it marked them as outsiders. Their outreach efforts failed, Leah says.

But after they began renting a house in Walltown, Jonathan was still viewed with suspicion because he was a Duke student. Some residents saw them as a plant from the university, there to check up on the community. Others thought they were spies for the police. Bahari Harris, a black Walltown resident who moved here to run a summer camp with the Navigators, says the neighborhood is a place from which you escape, so no one could imagine a pure motive for moving in.

Cultural differences added to the suspicions. It is strange to blacks that the Wilson-Hartgroves owned no television or new clothes and didn't eat meat. "But the way they entered the community was appreciated," Harris says.

"Jonathan made it his home, so he was just like one of the brothers," St. John's Hayes says. "They were willing to become like us to win the community, like Christ did for the church."

For Leah, life in Walltown is a far cry from family life in Santa Barbara, California, where she grew up, a daughter of author and former Westmont professor Jonathan R. Wilson. When Leah was working with a ministry in Walltown, she met Nora Poteat, whose son was about to be released from jail. The two developed a friendship, and when Poteat told Leah that her son had no place to live when he got out of prison, Leah and Jonathan invited Roy to live with them at Rutba House. "Everybody who needs someplace to go, they take," Poteat says.

After two years, Jonathan and Leah's idea for a reconciliation community is bearing fruit. Rutba House also took in Alvin Black, a 16-year-old who needed a place to stay. Isaac Villegas, a Hispanic Duke student, also lives at Rutba House and worships at a nearby black congregation. The community uses a modified common purse, but Jonathan says they may decide to hold all things in common in order to wipe out the financial differences between community members. The house is a ministry of Chapel Hill Mennonite Fellowship.

Jonathan says his daily practice of contemplation provides the spiritual strength to do ministry work. Fighting against structural oppression only attacks one side of the equation, he says. People are also oppressed by sin, and contemplation teaches the soul to be liberated.

The reconciling community practiced at Rutba House is a testimony both to Walltown and to suburbanites, says Amy Laura Hall, a professor at Duke Divinity who lives a block away from Rutba House in the "buffer" community. "The new monastic movement is called to live in daily ways counter to the suburban pull of isolation and homogenization," says Hall, an ethicist who is working on a book about the rise of the scientifically calibrated family. "The suburbs have become about safety, about protecting yourself from the kinds of people who are unclean. But Jesus sat down and ate with people who were supposed to be avoided."

Shaming Messages

The new look at the gospel is what makes community-living movements like the new monasticism an important part of the larger church. John Perkins—founder of the Christian Community Development Association, of which Claiborne is a board member, and of Antioch, an interracial community in Mississippi where Chris Rice lived for 14 years—says when those of privilege can give it up to live among those in need, it mirrors Christ coming to earth. "We have lost that incarnational concept. Jesus relocated down here to become a human being so we could be touched by him."

It's always a good thing when people decide to live out their love for Jesus in radical ways, says Ron Sider, professor at Palmer Theological Seminary (formerly Eastern Baptist). Many young people, he says, "look at society and the church and see an incredibly individualistic community and, in spite of some exceptions, still largely unconcerned for the poor."

However, in intentional community movements, one sometimes senses an element of guilt that is used to manipulate suburban youths into giving their lives to work with the poor. "And the flip side of that [guilt] tends to be self-righteousness projected on everyone else," says Jenell Williams Paris, who lived in community during college and graduate school from 1991 to 1999 and now teaches anthropology at Bethel University in Minnesota.

"I heard speakers give prophetic messages, part of which I now understand as shaming messages to white, middle-class evangelicals. I heard, 'White people aren't doing anything. Evangelicals don't care," Paris says. "I took that personally, and I thought, I don't not care; I just didn't know."

A summer with Bart Campolo's ministry gave her the conviction to work on behalf of the poor and influenced her life down to the person she married. However, Paris says, "That sense of shame and guilt was driving me for eight or ten years. Now I listen closely when evangelical social justice speakers come to my university. It's important to help students engage with justice issues out of love, not just out of white guilt."

Community living is also difficult, especially for families, to sustain over the long term. "The whole [American] culture is set up for married people with careers and kids to live in houses and to be mobile as a unit," Paris says. That can cause problems for communities that include married couples and their children, who at some point feel the need to move on to create a life for their family.

This sort of rhythm "reinforces the love-them-and-leave-them pattern," says Don Stubbs, director of recruitment for Inner City Impact in Chicago. Inner-city hopelessness is so deeply rooted that ministry takes years of building one-on-one relationships before it is effective, Stubbs says. Community living can be "sexy" ministry, but Stubbs says he would rather find workers committed long term to the urban setting.

Remonking the Church

Though the movement is relatively small and intimidating for many, for others it has become an attractive option for living the Christian life. Bessenecker says many young Christians today are looking to commit themselves to something far more radical than the suburban evangelicalism of their parents. We've lost the art of vow-making, he says. "In a community that has become so connected to their iPods and gaming, calling people to something different is the sort of challenge they're ready to rise to. It's their response to the abundance sickness that marks Western society."

A group of "monks" could help American Christians better stand against the pervasive consumerism and individualism of pop culture by providing an ideal of unworldly living. As CT wrote in 1988, such a remonasticization "would look to the biblical antecedents for a select group of holy persons set apart to call all persons to holiness, such as the Old Testament Nazirites … and Jesus' calling of disciples to train and teach with the goal of drawing all Israel to the same discipleship."

This new monasticism also provides a space for singles to contribute in sacrificial ways to the work of Christ in the world, Claiborne says. "There is something beautiful about singleness," he says. Those struggling with their sexual identity, or those unsure if they're called to marriage, "need a space for community, for love, and intimacy," which the new monasticism provides.

"The worship of family and the white picket fence is distasteful to the coming generation," Bessenecker says. A community of single people can represent God's expanded view of the family, that we are all brothers and sisters in Christ.

Though the new monasticism is a minority movement, Bessenecker says its impact could be far beyond the numbers of people involved. "None of these historical movements were ever a huge percentage of the Christian population," he says. "But they had a disproportionate impact on society. I think we're going to see that in the next 50 years."

Rob Moll is online assistant editor of Christianity Today.

Copyright © 2005 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

A More Demanding Faith | Christian history is full of attempts to lead a more radical faith.

Ct Classic

Remonking the Church | Would a Protestant form of monasticism help liberate evangelicalism from its cultural captivity?

Drop Out and Tune in to Jesus | Today's communities are very different, and very similar to, those that formed in the 70s.

More about the Camden House and the Simple Way are available from their websites.That