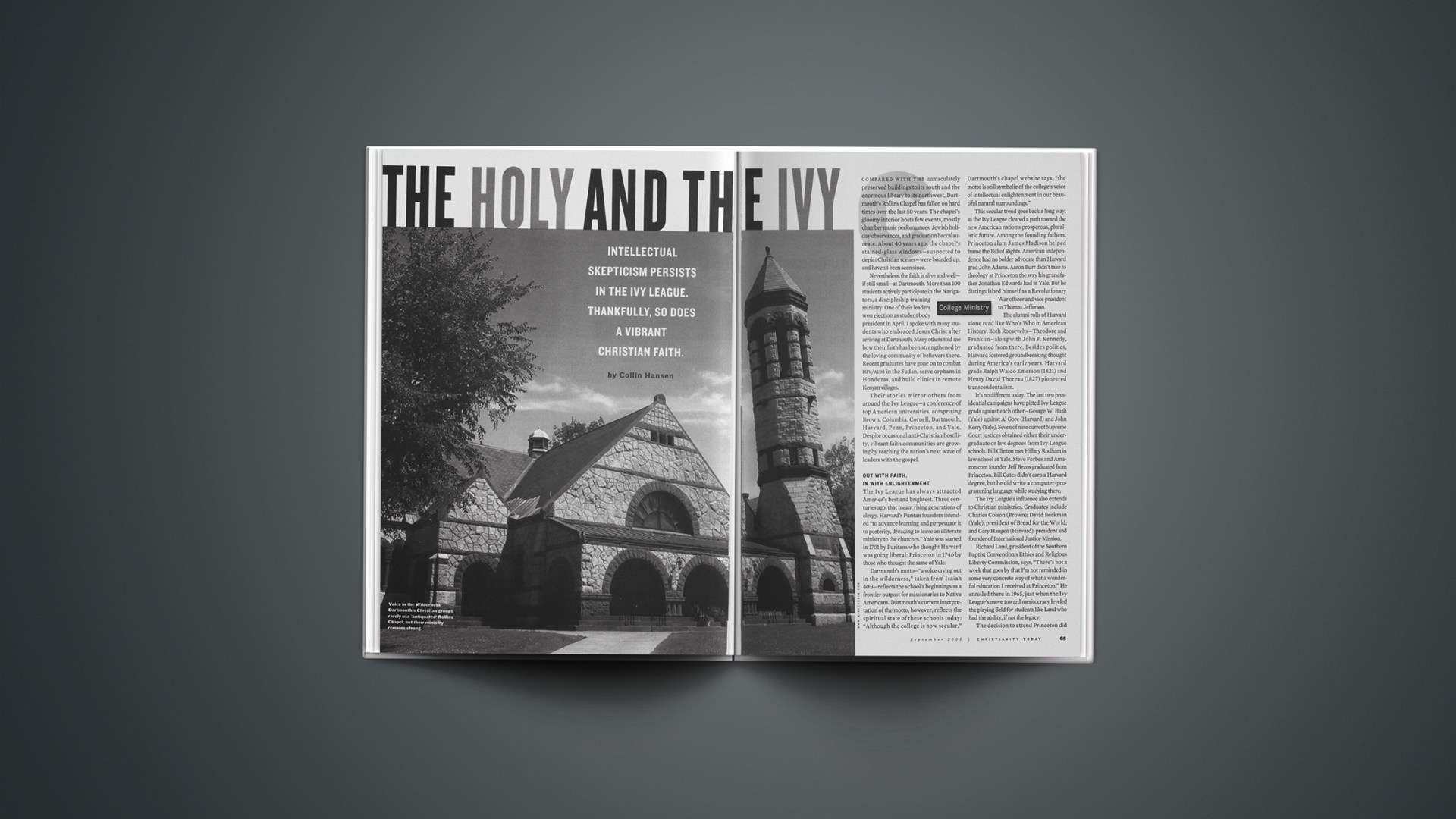

Compared with the immaculately preserved buildings to its south and the enormous library to its northwest, Dartmouth’s Rollins Chapel has fallen on hard times over the last 50 years. The chapel’s gloomy interior hosts few events, mostly chamber music performances, Jewish holiday observances, and graduation baccalaureate. About 40 years ago, the chapel’s stained-glass windows—suspected to depict Christian scenes—were boarded up, and haven’t been seen since.

Nevertheless, the faith is alive and well—if still small—at Dartmouth. More than 100 students actively participate in the Navigators, a discipleship training ministry. One of their leaders won election as student body president in April. I spoke with many students who embraced Jesus Christ after arriving at Dartmouth. Many others told me how their faith has been strengthened by the loving community of believers there. Recent graduates have gone on to combat HIV/AIDS in the Sudan, serve orphans in Honduras, and build clinics in remote Kenyan villages.

Their stories mirror others from around the Ivy League—a conference of top American universities, comprising Brown, Columbia, Cornell, Dartmouth, Harvard, Penn, Princeton, and Yale. Despite occasional anti-Christian hostility, vibrant faith communities are growing by reaching the nation’s next wave of leaders with the gospel.

Out with Faith, In with Enlightenment

The Ivy League has always attracted America’s best and brightest. Three centuries ago, that meant rising generations of clergy. Harvard’s Puritan founders intended “to advance learning and perpetuate it to posterity, dreading to leave an illiterate ministry to the churches.” Yale was started in 1701 by Puritans who thought Harvard was going liberal; Princeton in 1746 by those who thought the same of Yale.

Dartmouth’s motto—”a voice crying out in the wilderness,” taken from Isaiah 40:3—reflects the school’s beginnings as a frontier outpost for missionaries to Native Americans. Dartmouth’s current interpretation of the motto, however, reflects the spiritual state of these schools today: “Although the college is now secular,” Dartmouth’s chapel website says, “the motto is still symbolic of the college’s voice of intellectual enlightenment in our beautiful natural surroundings.”

This secular trend goes back a long way, as the Ivy League cleared a path toward the new American nation’s prosperous, pluralistic future. Among the founding fathers, Princeton alum James Madison helped frame the Bill of Rights. American independence had no bolder advocate than Harvard grad John Adams. Aaron Burr didn’t take to theology at Princeton the way his grandfather Jonathan Edwards had at Yale. But he distinguished himself as a Revolutionary War officer and vice president to Thomas Jefferson.

The alumni rolls of Harvard alone read like Who’s Who in American History. Both Roosevelts—Theodore and Franklin—along with John F. Kennedy, graduated from there. Besides politics, Harvard fostered groundbreaking thought during America’s early years. Harvard grads Ralph Waldo Emerson (1821) and Henry David Thoreau (1827) pioneered transcendentalism.

It’s no different today. The last two presidential campaigns have pitted Ivy League grads against each other—George W. Bush (Yale) against Al Gore (Harvard) and John Kerry (Yale). Seven of nine current Supreme Court justices obtained either their undergraduate or law degrees from Ivy League schools. Bill Clinton met Hillary Rodham in law school at Yale. Steve Forbes and Amazon.com founder Jeff Bezos graduated from Princeton. Bill Gates didn’t earn a Harvard degree, but he did write a computer-programming language while studying there.

The Ivy League’s influence also extends to Christian ministries. Graduates include Charles Colson (Brown); David Beckman (Yale), president of Bread for the World; and Gary Haugen (Harvard), president and founder of International Justice Mission.

Richard Land, president of the Southern Baptist Convention’s Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission, says, “There’s not a week that goes by that I’m not reminded in some very concrete way of what a wonderful education I received at Princeton.” He enrolled there in 1965, just when the Ivy League’s move toward meritocracy leveled the playing field for students like Land who had the ability, if not the legacy.

The decision to attend Princeton did not come easily for Land, however. His father and teachers lobbied for Princeton’s prestige. But his mother and pastor pushed for Wheaton College in Illinois.

“The argument for the Wheaton people was, You can’t go into a cold spiritual icebox like Princeton and come out spiritually hot,” he recalled. “And the argument on the other side was, You can’t go into a hothouse like Wheaton and come out and face the cold wintry blast of the world.”

Asian Explosion

Matt Bennett, founder and president of the Christian Union, an Ivy League ministry based in Princeton, New Jersey, acknowledged that the sometimes-hostile atmosphere precludes moderation. “Faith is either hot or cold in these places,” Bennett said. “If it’s casual, you’ll get swept up. If you’re for Christ, you’re known for it.”

But local churches and parachurch ministries are helping today’s Christian students be known for their faith. Land says he is “amazed at how much stronger the evangelical presence appears to be on campus now” than when he attended in the late 1960s.

One reason for this upsurge dates back 40 years. With the Immigration Act of 1965, Congress abolished nationality quotas and ordered that immigrants were to be admitted based on their professions and skills. The bill opened the immigration floodgates for Asian professionals. Nearly 20 years later, the children of these doctors and engineers—many of them Christians from China and Korea—applied to Ivy League colleges. Wanting accomplished and racially diverse student bodies, the Ivy League obliged.

Now, Asians account for nearly 14 percent of Ivy League undergraduates. At Penn, the proportion is almost one-quarter. Asian Americans are the majority of many major Ivy League campus ministries.

Jimmy Quach leads Harvard-Radcliffe Asian American Christian Fellowship (HRAACF), a ministry affiliated with InterVarsity Christian Fellowship, an evangelical campus mission. His family fled Vietnam for America at the end of the war in the mid-1970s. He attended Harvard, and graduated in 1998 with majors in economics and applied mathematics. But when he first showed up at Harvard, his faith was nominal. Quach says his Asian church perpetuated the struggles that afflict many young Asian Americans—namely, conditional love based on performance. Harvard seemed to be more of the same, until he ran into HRAACF.

“At Harvard there’s a lot of mutual sizing up. Other students ask about your sat score,” Quach said. “[HRAACF] was the first group on campus where they didn’t ask my score. They just wanted to know me and be friends.”

Community Is Key

The students and ministers I spoke with universally identified loving faith communities as the frontier of evangelism in the Ivy League. “Community is a huge draw for this generation—even more than 10 years ago,” said Tom Sharp, head of Yale Christian Fellowship. “In other words, community is probably a stronger draw than anything apologetic anymore for most students.

“The front-door issues are these big intellectual questions. But it’s like they debate because they’re trained to do it, because they do that in their classes. The gospel doesn’t enter the front door anymore. It seems like their experience of community is the back-door entry.”

As David Brooks famously explored in his Atlantic Monthly article “The Organization Kid,” Ivy League students can argue any position, like finely tuned intellectual machines. They don’t have to believe in their thesis to defend it. On the contrary, vulnerable communities can’t be faked. Christian communities provide a rare safe haven from cutthroat situations like student government and pre-med classes.

Tyler Stahl discovered that sort of inviting environment in the Navigators when he arrived at Dartmouth four years ago. Not then a Christian, Stahl said his dorm was a “hotbed of Christian activity.” He attended Navigators meetings so his friends would stop inviting him. After a couple years, the ministry even asked him to join their planning committee, despite his lingering intellectual doubts about the gospel.

Last fall, the beginning of his senior year, Stahl began feeling a nagging loneliness. But he had plenty of friends. Instead, he longed for God.

“All of a sudden, my doubts didn’t seem so impressive,” Stahl said. He put his faith in Jesus Christ.

Stahl’s experience reflected Quach’s ministry at Harvard. “We still need to debate the truth,” Quach said. “We don’t necessarily have to talk students into Christianity, but they have to understand that the Christians around them are not stupid. They need to know that we’ve dealt with all the issues, but that [faith in Christ] makes sense. It’s often enough for them to just see that others have wrestled with doubt.”

To that end, Yale’s Tom Sharp focuses on fostering enduring relationships. About five years ago, Sharp became concerned with the lackluster results of their large-scale outreach events. Short of Billy Graham, the biggest Christian names didn’t impress Yale students, accustomed to visits from top-notch world figures.

So Sharp and his staff devised a new strategy. Given the students’ social-justice mindset, they planned a spring-break trip with Habitat for Humanity. To encourage Christians to invite their unbelieving friends, they recruited a donor to fund two-for-one deals.

This year—their fifth trip—about 50 students from Yale and nearby Wesleyan University built homes in Jacksonville, Florida. Nearly half of the students had little or no church background. In talking with Christians about their distinct motivation for helping the poor, five students committed their lives to Christ.

Cooperation, Not Compromise

Richard Stearns, World Vision U.S. president, did not become a Christian until shortly after he graduated from Cornell in 1973. But the evangelistic ministry Campus Crusade for Christ still shaped him.

“My senior year, about a month before graduation, I met [my future wife] on a blind date,” Stearns recalled. “I was the worst kind of agnostic back then, an obnoxious one and thinking I knew all the answers. She was a freshman and I was a senior. So in a lull in the conversation, she pulled out the Four Spiritual Laws and said, ‘I have something to share with you. God loves you and has a wonderful plan for your life.’ I looked back at her and said, ‘You’re kidding.’ She said, ‘No, I’m very serious. Can I continue?’ And she took me through the Four Spiritual Laws, which she had been trained to do at Campus Crusade.”

Two of their children followed their lead to Cornell. But Stearns says the environment has grown so hostile to Christian beliefs that he will probably send his youngest two children elsewhere. His son who graduated last year sparred with the Cornell administration over required classes promoting homosexuality and abortion. Stearns says his daughter endured much scorn during the 2004 election.

According to Ivy League campus ministers, politics has become a stumbling block in evangelism. Craig Parker, staff leader for Navigators at Dartmouth, says his ministry does not use the term evangelical, due to its “political and moralistic connotations.” Jimmy Quach says Harvard students loathe the Religious Right. He said, “One student told me, ‘I love everything I’ve learned about Christianity. I love the community. I love what I’ve learned about Jesus. But if I were to become a Christian, I’d have to consider those in the Religious Right in my family. And I can’t stand that idea.'”

Ministries figure out ways to work in the harsh climate. They seek what common ground they can with campus activists. When liberal groups lobbied Harvard administrators to divest from companies that do business with Sudan, Quach said HRAACF members wrote home asking their churches to pray against the genocide. HRAACF also joined a campus rally against sexual violence.

“We tell those groups, Yeah, we’ll stand with you on all that stuff,” Quach said, “but that doesn’t mean we’ll accept liberal sexual ethics or abortion.”

‘Like Diamonds on Black Velvet’

Concerned evangelical parents call Pat McLeod all the time to ask if their children’s faith will survive Harvard. The Campus Crusade for Christ staffer even has a standard response.

“There is a thriving evangelical movement at Harvard,” he explains. “Our movement has more than doubled in size, from 70 in the fall of 1999 to 150 this year.”

The growing edge has been the Alpha Course, a 10-week introduction course to the Christian faith. Two years ago, 12 students accepted Christ through Alpha. From that group, two students have enrolled in seminary, and another will serve next year as a missionary in East Asia.

McLeod says the course reaches both the modern and postmodern sensibilities of today’s students. Alpha uses traditional apologetics, but discussion leaders don’t argue to defend Christianity. Other Christians in the group share why they believe in Christ. New Christians eagerly invite their friends to participate. McLeod says, “The gospel spreads through relational networks.”

Indeed, God’s message of salvation has always spread this way. But when your relational network is students at Harvard or elsewhere in the Ivy League, the wider culture can be deeply affected. Look no further for the nation’s next generation of business leaders, politicians, and academics. Even without institutional encouragement from their schools, some students will pursue calls to pastoral ministry and the missionary field.

“Dartmouth is never going to become Wheaton again,” Navigators leader Parker said. “I’m not going to reclaim the Ivy League. In some ways, I appreciate the contrast. It’s like diamonds on black velvet, the Christians who are here in the midst of this environment.”

Rollins Chapel reminds Parker of that black velvet. Every term, as he scrambles to find a place for Navigators to meet, he laments the antiquated chapel and its hidden windows.

“It’s not just religious people saying [we should uncover the stained-glass windows],” recent Dartmouth grad John Stern said. “People who know about art say, ‘This is an artistic masterpiece. It needs to be uncovered.’ People who know about architecture and lighting say, ‘This building is so bleak without the light.'”

But there’s hope yet for the windows. Dartmouth chaplain Richard Crocker told me that the college administration has recently agreed to uncover them. Seems they want to see the chapel with the light.

Collin Hansen is an associate editor of Christianity Today.

Copyright © 2005 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

The Navigators, Campus Crusade, The Christian Union, Harvard-Radcliffe Asian American Christian Fellowship, and Yale Christian Fellowship have more information about their ministries.

Books & Culture magazine recently explored the differences between Bethel University and Harvard.

Other recent CT articles on education include:

A Higher Education | A slew of new books on faith and learning may signal a renaissance for the Christian college. (May 27, 2005)

Baylor Showdown | Provost fired. Faculty question school’s direction. (July 14, 2005)

Big Chill | Anti-religion group seeks to block federal funding of Alaska school. (June 16, 2005)

Designed Dispute | Curriculum critical of evolution nears approval in Kansas. (June 13, 2005)

Myths of the Faith-Based Campus | Why Blue America need not be appalled by religious colleges. (May 04, 2005)

No Compromise | Christian school in Colorado alleges discrimination in voucher program. (Feb. 09, 2005)

Christian Ed That Pays Off | Grand Canyon University becomes the first for-profit Christian college. (Feb. 02, 2005)

Open or Closed Case? | Controversial theologian John Sanders on way out at Huntington. (Dec. 22, 2004)

Masters of Philosophy | How Biola University is making inroads in the larger philosophical world. (June 13, 2003)