In 1969, 35-year-old Jack Hayford pulled up to a traffic light in front of First Baptist Church of Van Nuys. Like any other pastor in Southern California, he knew of the Baptist congregation. It was growing like a weed, drawing nationwide publicity under the leadership of Pastor Harold Fickett. Hayford's church, a few blocks down Sherman Way, was an aging Foursquare congregation with just 18 members. Two weeks before, Hayford had taken on the church temporarily while serving as dean of students at L.I.F.E. Bible College (now Life Pacific College), an institution of his Pentecostal denomination, the International Church of the Foursquare Gospel.

Parked at the light, Hayford felt a burning sensation on his face, a startlingly physical sense of the church's intimidating presence. Through an inner voice God spoke to him, reprovingly: "You could at least begin by looking at the building."

He turned and saw nothing but a modern brick structure. "What now?" Hayford asked.

"I want you to pray for that church," God said. "What I am doing there is so great, there is no way the pastoral staff can keep up with it. Pray for them."

As Hayford began to pray, he felt an overflow of love for Van Nuys Baptist. It seemed to take no effort. Through the days to come, the same sensation came to him every time he passed by a church—any church. "I felt an overwhelming love for the church of Jesus Christ. I realized I had them in pigeonholes."

A few days later, he approached a large Catholic church. Having been raised to take strong exception to Catholic doctrine, he wondered whether he would have the same feelings. He did, and heard another message from God: "Why would I not be happy with a place where every morning the testimony of the blood of my Son is raised from the altar?"

"I didn't hear God say that the Catholics are right about everything," Hayford says now, remembering the experience that changed his ministry. "For that matter, I didn't hear him saying the Baptists are right about everything, nor the Foursquare."

The message was simply that people at those churches cared about God. These were sites dedicated to Jesus' name. And he, Hayford, was supposed to love and pray for them.

Kingdom Bridges

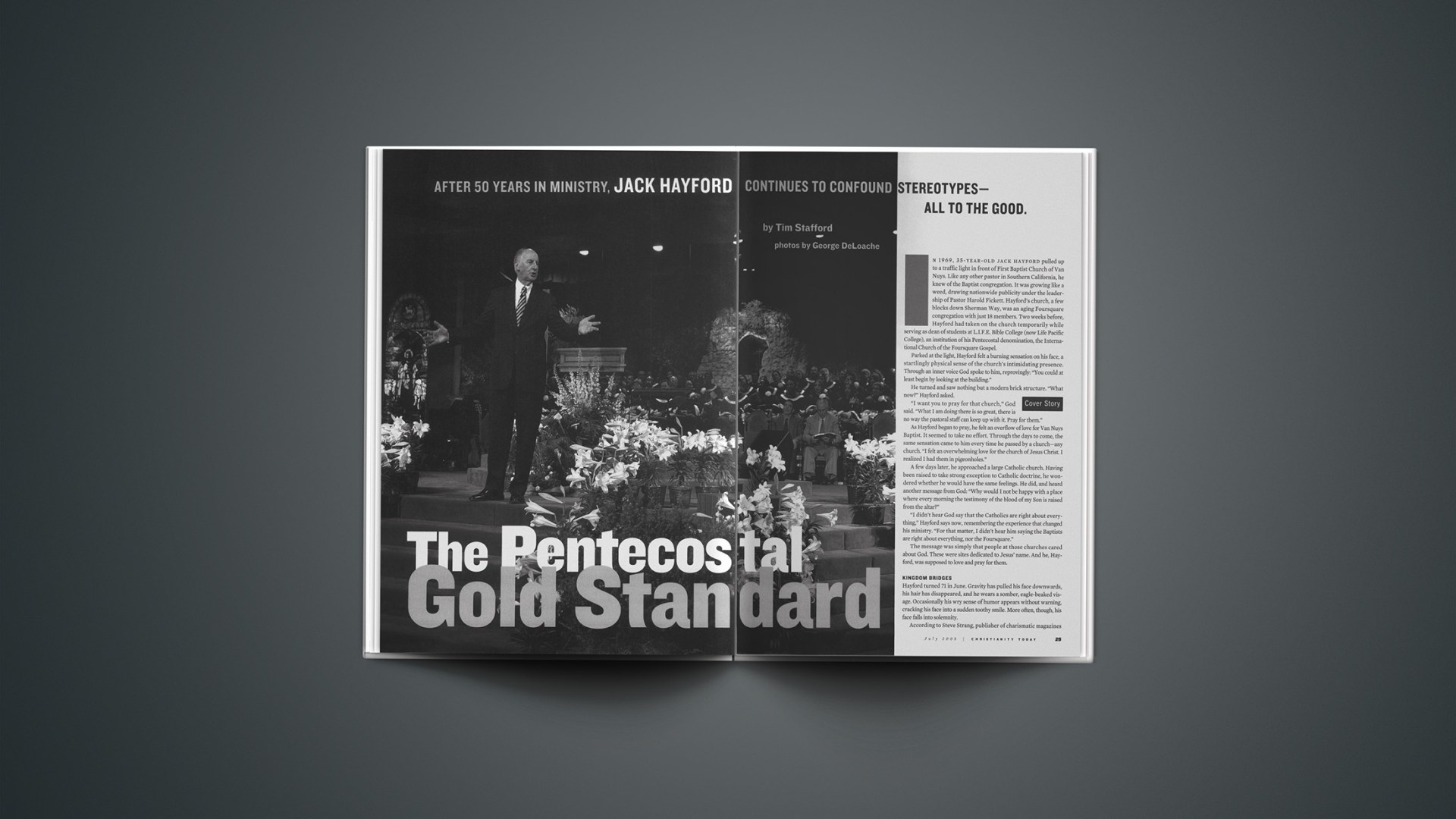

Hayford turned 71 in June. Gravity has pulled his face downwards, his hair has disappeared, and he wears a somber, eagle-beaked visage. Occasionally his wry sense of humor appears without warning, cracking his face into a sudden toothy smile. More often, though, his face falls into solemnity.

According to Steve Strang, publisher of charismatic magazines Charisma and Ministries Today, Hayford has emerged as Pentecostals' and charismatics' gold standard. "Pastor Jack would fall into a category of statesman almost without peer," Strang says. "His integrity and theological depth are so well known that he can draw together all kinds of factions."

In Southern California, he is known as founding pastor of the Church on the Way, a congregation of 10,000 that he built from that struggling 18-member start in Van Nuys. Its one-time Anglo suburban neighborhood has become gritty Latino turf, but the church has not moved. Hayford has a strongly physical sense of God's work, and he believes that the Church on the Way was called to that very location. Spanish-language services have become the leading edge of the church, averaging 6,000 in weekly attendance.

Having reached an age when it would be reasonable to retire into statesmanship, Hayford has taken on more challenges. Last fall he was elected president of the Foursquare denomination, replacing a predecessor who resigned after the church lost $15 million in a phony investment scheme. Seven years before that, his predecessor resigned under similar circumstances. Intensely loyal to his denomination, Hayford intends to reinvigorate a discouraged institution.

He only recently completed another emergency assignment, coming out of retirement when Scott Bauer, his son-in-law and successor at Church on the Way, died unexpectedly. Hayford steered the church through that crisis, while continuing his leading role at the seminary and Bible college he founded—King's College and Seminary, ironically located on the former campus of Van Nuys Baptist. In addition, one week of every month he leads the Jack W. Hayford School of Pastoral Nurture, a five-day seminar for pastors at which he speaks for six to eight hours a day on his philosophy of ministry.

Hayford continues to write, teach on radio and TV, and speak all over the world. His latest of some 40 books has just been released: Manifest Presence: Expecting a Visitation of God's Grace Through Worship (Chosen).

Hayford brings Pentecostals together with other evangelicals. He has done this less through grand strategy than by patient outreach, one person at a time. In his public speaking he makes frequent, appreciative references to non-Pentecostal influences, from C. S. Lewis to Richard Foster. He reaches out to other L.A.-area pastors. John MacArthur counts him as a friend despite their many theological differences. Presbyterian pastor and former Senate chaplain Lloyd Ogilvie considers him one of his oldest and dearest prayer partners.

Likewise, there is hardly an evangelical leader Hayford does not know and speak well of. He is reliably involved as a leader in interdenominational activities, from mayoral prayer breakfasts to the recent Los Angeles Billy Graham Crusade (which he co-chaired). A prominent speaker at Promise Keepers rallies, he has been heavily involved in efforts at racial reconciliation.

He does all this without toning down his Pentecostalism one decibel. He is, in fact, aggressive about his beliefs, though he presents them graciously, in a way that explains and persuades. Leadership editor Marshall Shelley recalls hearing Hayford at a prayer summit at Multnomah Bible College. Most of the gathered pastors were conservative non-Pentecostals.

"By the time he was done, he had most of those pastors lifting their hands in praise," Shelley says. "He did it by explaining why it was biblical and why it mattered. He made sense. He brought rationality to spiritual expressiveness."

Hayford does not always get the same respectful treatment in return. One reason he is sensitive to racial injustice, he says, is because he experienced parallel mistreatment as a young Pentecostal. Prejudice is fading, he believes, but it still galls him that some bookstores won't stock his books, and that certain radio networks exclude him.

"I made a very distinct choice [to be a full-strength Pentecostal]," he says. "I could have been more reserved, silent on things that were my true conviction, but you don't make headway against prejudice by compromise."

He can be sharply critical of non-Pentecostal positions, such as what he sees as the temptation of Reformed thinking to fall into fatalism. "Reformed theology has … ended up creating a monster of theology that dampens the place of our passion and partnership with God."

He is quite willing to critique fellow Pentecostals too, and admits that charismatic televangelists can be extremely imprecise in their theological utterances. He tends to excuse them, though, as well meaning and excitable. If you're choosing up teams, there is no doubt where his sympathies lie. That makes it all the more remarkable how far he extends himself outside of Pentecostal circles.

David Moore, a Ph.D. candidate at Regent University who is writing his thesis on Hayford, notes that Hayford's Lausanne II address, given in Manila, was entitled "Passion for Fullness." In Hayford's vocabulary, "genuine spiritual fullness is bridge building. To be fully Pentecostal means being open to the fullness and breadth of the church. If you have a commitment to building the kingdom of God, you have to be committed to the church beyond the sector you're in." Hayford conveys remarkable graciousness toward those who disagree with him, as well as to those who have fallen from grace. Thus he has invited both John MacArthur and Jim Bakker to preach in his church.

Hayford likes to note the cornerstone of the Angelus Temple, from which founder Aimee Semple McPherson built the Foursquare denomination. It reads, "Dedicated unto the cause of Inter-denominational and World Wide Evangelism." Like McPherson, Hayford works within a church and a denomination, but his eyes look outward.

The Lord's Voice

Hayford tells many stories that feature the Lord's voice. He doesn't hear audible sounds, he says, but receives strong mental impressions, sometimes so clear that he feels he could almost say, "The Lord told me, and I quote." Though always mindful to assert that the ultimate voice of God is found in the Scriptures, he describes guidance aided by vivid mental pictures and dreams. Many of his most pivotal moments came as a result of such experiences.

"I'm not glib about that," he says. "The Lord and I don't have an ongoing conversation. We do have an ongoing relationship." A daily, attentive, childlike relationship with God is at the heart of Pentecostal belief, Hayford thinks, and he wishes it for every Christian.

Not surprisingly, it was divine guidance that first prompted him to take on the pastorate of a tiny, aging congregation in Van Nuys. Hayford had already turned down one of the most prestigious pulpits in the denomination. Young and rising in reputation, he agreed to take a six-month interim in Van Nuys only because he would be free to go to a more significant church when fall rolled around.

He was in the denomination's downtown L.A. offices, conversing with Rolf McPherson, head of Foursquare and son of founder Aimee Semple McPherson, when quite apart from the conversation "there descended on me an awareness that I was to stay at the church. It was not a delightful realization." His first congregational meeting had 16 of the 18 members in attendance. The average age was more than 65. He remembers their faces shining with joy—not because they grasped what he said about his goals in ministry, but because he was young. They saw a young, dynamic pastor, his wife and children, and they felt hope.

Hayford says he had two main pastoral ideas in mind when he began in Van Nuys. One was an emphasis on the ministry of all believers. The pastor's job, described in Ephesians 4:11-12, was to equip the congregation for ministry, not to do the ministry himself. The second idea was the priority of worship, coming before evangelism and mission in the life of the church.

Neither idea was unique. In northern California, a Bible-church pastor named Ray Stedman was gaining national attention preaching about "body life" using exactly the same passage in Ephesians. Meanwhile the Jesus movement had brought an upsurge in contemporary music that would lead to vastly increased appreciation for worship all over.

Hayford, however, integrated these ideas with a strong, practical, and Pentecostal theology of the kingdom of God. "His motivation is to get theology into people, to get it lived out," says Pastor Jim Tolle, who attended the church in its early days after coming home from Vietnam. (After years heading the church's Hispanic ministry, Tolle has become its senior pastor.)

If Pentecostals are not stereotypically theological thinkers, Hayford breaks the stereotype. "What an outstanding intellectual Jack is," Lloyd Ogilvie notes. "He is a deeply rooted scholar in the biblical tradition."

'Blended' Worship

On a Saturday night, Hayford was praying through his church sanctuary. He likes to do this every Saturday night—to go through the room laying hands on each seat, praying for God's blessing on the people who will sit in them Sunday morning.

It's typical that his view of God's working in the congregation is so physically rooted, right down to the actual seats in the actual room. This is his preparation for Sunday worship: praying over the place.

On this occasion, he was with two other staff members when a college-age member knocked on the door. She had noticed some activity and came over to see whether she could join in. Hayford felt led to direct them into the four corners of the sanctuary, where they raised their hands up and over the space between them, as though extending a canopy. For some time they sang spontaneously before the Lord.

When they were done, they felt deeply moved, for reasons they could not quite explain. The youth pastor, Paul Charter, made a suggestion. "The Lord impressed on me that the reason the experience seemed so profound was that we were standing with angels, blending with them in worship."

Hayford thought no more of it until the next Tuesday, when he attended the early morning men's prayer meeting. He was "feeling tired … as spiritual as a toad." Despite that, the Lord spoke to him during the meeting. "The angelic creatures I showed Paul are the four living creatures of Revelation 4."

"I'm thinking, 'Of course,'" Hayford says sardonically. "'Where else but in Van Nuys.' I'm thinking, This is the way kooks start. Entire cults began with less than this." Nevertheless he got up on the platform and read to himself the passage from the pulpit Bible—John's vision of ecstatic worship around the throne of God.

Ten days later, Hayford says, in the church parking lot, he suddenly caught a mental picture so vivid that he understood God's message. What he saw was an alignment between the throne of God described by John, and the church he pastored on Sherman Way in Van Nuys. One seemed to blend into the other: vast multitudes of praising creatures in John's vision overlapping with the praising people of the Church on the Way. As Hayford saw it, the entire San Fernando Valley, ten miles wide, became an amphitheater of praise surrounding God's throne.

Reality, as Hayford came to grasp it, is that God works simultaneously in the visible and the invisible, in the physical and the spiritual. The worshiping church stands at the heart of his reign. Thus the church Hayford pastored (and any church, potentially) was more than a gathering of people dedicated to a far-off spiritual kingdom and to somewhat abstract principles. The church at worship became an expression of the power of the kingdom of God, with the literal presence of God in the middle of its sanctuary.

David Moore says Hayford's theology of the kingdom of God is strikingly similar to George Eldon Ladd's. The difference, Moore says, is that "Ladd doesn't make the application. He says a lot of the same things, but he doesn't apply them with the same dynamism."

Hayford's passion is the kingdom of God operating in the here and now, with power, through the church—any church, big or small. Though he grew a megachurch, Hayford cares little for techniques of church growth. His idea of spiritual warfare centers on a worshiping congregation.

That is why classically Pentecostal forms of worship matter. He believes in pushing people out of their comfort zone into the free exercise of congregational singing, of praise, of shouting before the Lord. Such worship liberates people to live out the kingdom of God. Therefore people's self-awareness, their reluctance to let themselves go in praise, is an obstacle pastors must forcefully confront.

"It is infinitely easier," Hayford says, "to cultivate a congregation that will listen to the Word of God than to cultivate a people who will worship God."

He believes lifting hands to God is more than an option, it is a timeless demand suited to our bodies. Music, too, taps in to God's power. Hayford is a musician who has written more than 400 songs, including the well-known "Majesty." He understands congregational singing as a God-mandated form for praise.

While Hayford subscribes to Pentecostal doctrine that tongues is a "sign gift," indicating the baptism of the Spirit, he doesn't think the point can be conclusively proved one way or the other from Scripture. Instead he emphasizes that tongues is a useful gift—useful to the worshiper in prayer, and thus useful to the kingdom of God, which works through praying believers. "I have a passion to move every Christian to the free exercise of tongues," Hayford says, "not as a proof of spirituality but as a privilege for worship and intercession."

He thinks the obstacle to speaking in tongues is less theological than personal—people's fear of the unknown. Here too pastoral leadership is needed, he says, because tongues enables God's people to pray effectively even when they don't know how to pray.

Intercessory prayer, like worship, is a hallmark of Hayford's practical theology. Early on he instituted "prayer circles" at morning worship. The congregation breaks into small groups to pray for each other, for their community, and for the world. Prayer circles apprentice people in the service of prayer.

"If you expect them to do it at home," Pastor Jim Tolle says, "you have to walk through it in the service. We practice praying. We live it out in each of our services. And to tell you the truth, it's really not convenient. It's a turnoff for new people, who don't know what to do. It can get old. People can get ritualized in it. But we keep on."

Hayford takes prayer as a heavy responsibility. "If I don't pray for [my wife], Anna, there's a gaping hole of vulnerability." Prayer embraces much more than family and church matters. The fence in front of Hayford's home has 11 pillars, which he uses to remind him of 11 areas of responsibility that demand his prayer. One column is for his city. His vision of the physical-spiritual alignment tells him that the church's location in Los Angeles is no accident. He sees God's people going out from worship to affect every aspect of L.A.—from its ethnic diversity to its Hollywood glitz. He chokes up describing his "great affection in terms of mission to my city."

The church, he believes, should avoid any hint of political partisanship or Christian self-righteousness. He rejects "triumphalism that only sees triumph in getting exactly what you asked for." "I don't think we're called to silence, but we are called to sensitivity. We're not good at that." He does, however, believe in the church's call to make a difference on Earth, not merely to redeem people for a future in heaven.

'Tell the Truth, Jack'

Hayford was born in Los Angeles and dedicated in a Foursquare church in Long Beach. Most of his childhood, however, was spent in Oakland. His father was a switchman for the Southern Pacific railroad; his mother was a Bible teacher who spoke widely in interdenominational women's classes and in Women's Aglow Fellowship (now Aglow International). Neither parent graduated from high school, but they were outward looking and "a talkative family," says Hayford's wife, Anna. "They had wild discussions."

Hayford admired both his parents, but "he is exactly like his mother," Anna says. Like Jack, his mother "could be very demanding." But she was a compassionate woman, "always championing the cause of someone not so lovable."

"The first time I interviewed [his mother], Delores, I was just taken aback," says David Moore. "I thought, 'I'm meeting Jack Hayford.'" Moore mentions her quick wit, her precision, and her broad awareness.

From his mother, Hayford got his intellectual curiosity (lately he is reading on string theory), and his strong sense of accountability before God. He remembers her saying, "Tell me the truth, Jack, in the presence of Jesus." He never took this as manipulative: The sense was that since Jesus knew the truth, Jack couldn't gain much by concealing it.

For 10 years, until Jack was 14, his father refused to go to church, where his smoking and occasional lapses into drinking would be looked down on. Out of loyalty to her husband, Hayford's mother stayed home too, sending her children off to church without her. "He once beat me up," Hayford says of his father, "and Mother threw herself over me." She protected her 10-year-old cub and warned off her husband in no uncertain terms.

Hayford grew up with a keen religious awareness. "He probably has the healthiest sense of the fear of God of anyone that I've ever met," says Jack Hamilton, his longtime colleague in ministry. In college, Hayford noted the angel Gabriel's words in Luke 1:19: "I am Gabriel, and I stand in the presence of God." In the margins of his Bible, Hayford wrote, "May this always be true of me." He has endeavored to live in that kind of God consciousness. His "fear of the Lord" embraces his obedience to God's daily leading.

For example, Hayford doesn't believe that the Scriptures require teetotalism, but he says that many years ago the Lord impressed on him that he personally ought not to drink wine. Then, "Seventeen years ago, in my kitchen, the Lord spoke to me: 'Chocolate shall be to you as wine.'" Hayford understands that as a private but absolute mandate not to touch chocolate. "I believe that the Lord knows my body, and knows what is good for me. And I fear the Lord. I would not dare disobey. It's about as righteous as that I'm not going to step off the edge of a five-story building."

He studies Scripture with the same spirit. Every day he reads on his knees. It's a physical discipline reminding him that every word addresses him, so he must constantly ask, "What does this have to do with me?"

While Hayford encourages accountability groups and structures, he warns pastors that only accountability to God can protect them.

"Ultimately it's the only thing that will make me accountable to anyone else—my wife, my congregation, even myself."

Always, not far from his mind is the heavenly assembly, praising God around his throne. The kingdom of God is present in Van Nuys, California, even while creation waits for "the revealing of the sons of God" (Rom. 8:19). And always somewhere within Hayford's awareness are the words, "Tell me the truth, Jack, in the presence of Jesus."

Tim Stafford is a CT senior writer.

Copyright © 2005 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

More about Jack Hayford's ministry—including news and events, radio and TV, books, the school of pastoral nurture, is available on his website.

The Church on the Way has more information about Hayford's ministry, along with online spiritual resources.

International Church of The Foursquare Gospel has Jack Hayford's blog, more information about the denomination, and its news service.

Listen to Hayford's sermons at CT's sister online publication, PreachingTodayAudio and at OnePlace.com.

More recent Christianity Today articles on Pentecostalism include:

Hand-Clapping in a Gothic Nave | What Pentecostals and mainliners can learn from each other. (March 11, 2005)

Christian History Corner

The Roots of Pentecostal Scandal—Romanticism Gone to Seed | The sexual stumblings of prominent ministers point to a hidden flaw in Pentecostal spirituality. (Sept. 17, 2004)

Christian History Corner

Romanticism Gone to Seed—Part II | Have the holiness and Pentecostal movements really been "hyper-vertical" and "anti-domestic"? (Oct. 01, 2004)

God's Peculiar People | Historian Grant Wacker explains why Pentecostals survived and even flourished. (March 18, 2002)

Are Pentecostals Sex-Crazed? | John Steinbeck and Robert Duvall have portrayed them that way, and such criticism even came from inside the movement. But was it ever warranted? (Sept. 11, 2001)

Christian History Corner

Explaining the Ineffable | In Heaven Below, a former Pentecostal argues that his ancestors were neither as outlandish as they seemed nor as otherworldly as they wish to seem. (Aug. 31, 2001)

Should We All Speak in Tongues? | Some say speaking in tongues is proof of 'baptism in the Holy Spirit.' Are those who haven't spoken in tongues without the Holy Spirit? (March 6, 2000)

A Peacemaker in Provo | How one Pentecostal pastor taught his Congregation to love Mormons. (February 7, 2000)

Christian History & Biography devoted an issue to The Rise of Pentecostalism. More on Pentecostalism from CT sister publications include:

Whither Pentecostal Scholarship? | The overlap between "people with the Spirit" and "people with Ph.D.'s." (Books & Culture, May/June 2004)

El Espiritu Santo | Exploring Latino Pentecostalism. (Books & Culture, May/June 2004)

A Global Pentecost | The fastest-growing religious group? (Books & Culture, March/April 2002)