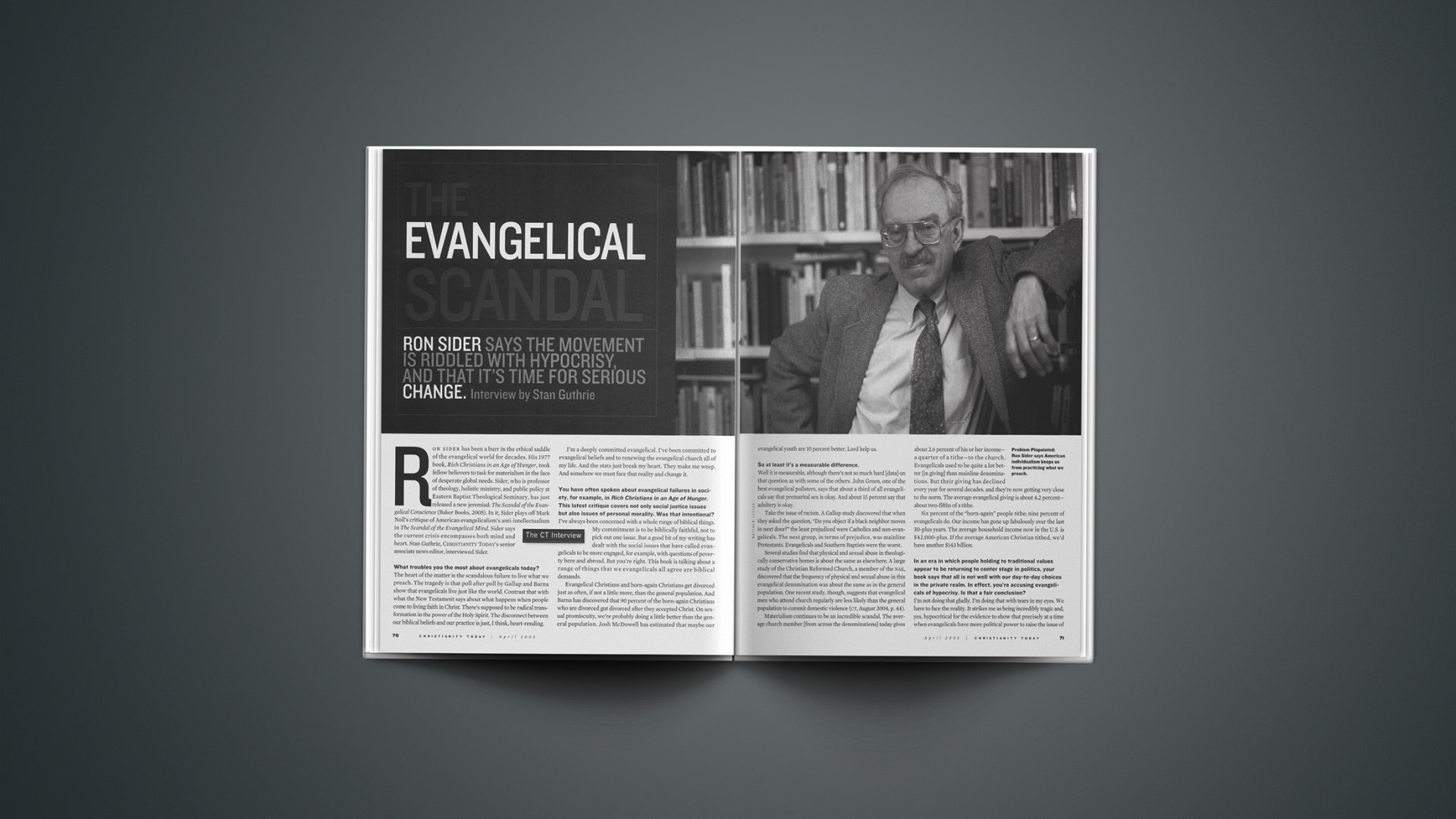

Ron Sider has been a burr in the ethical saddle of the evangelical world for decades. His 1977 book, Rich Christians in an Age of Hunger, took fellow believers to task for materialism in the face of desperate global needs. Sider, who is professor of theology, holistic ministry, and public policy at Eastern Baptist Theological Seminary, has just released a new jeremiad: The Scandal of the Evangelical Conscience (Baker Books, 2005). In it, Sider plays off Mark Noll’s critique of American evangelicalism’s anti-intellectualism in The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind. Sider says the current crisis encompasses both mind and heart. Stan Guthrie, Christianity Today‘s senior associate news editor, interviewed Sider.

What troubles you the most about evangelicals today?

The heart of the matter is the scandalous failure to live what we preach. The tragedy is that poll after poll by Gallup and Barna show that evangelicals live just like the world. Contrast that with what the New Testament says about what happens when people come to living faith in Christ. There’s supposed to be radical transformation in the power of the Holy Spirit. The disconnect between our biblical beliefs and our practice is just, I think, heart-rending.

I’m a deeply committed evangelical. I’ve been committed to evangelical beliefs and to renewing the evangelical church all of my life. And the stats just break my heart. They make me weep. And somehow we must face that reality and change it.

You have often spoken about evangelical failures in society, for example, in Rich Christians in an Age of Hunger. This latest critique covers not only social justice issues but also issues of personal morality. Was that intentional?

I’ve always been concerned with a whole range of biblical things. My commitment is to be biblically faithful, not to pick out one issue. But a good bit of my writing has dealt with the social issues that have called evangelicals to be more engaged, for example, with questions of poverty here and abroad. But you’re right. This book is talking about a range of things that we evangelicals all agree are biblical demands.

Evangelical Christians and born-again Christians get divorced just as often, if not a little more, than the general population. And Barna has discovered that 90 percent of the born-again Christians who are divorced got divorced after they accepted Christ. On sexual promiscuity, we’re probably doing a little better than the general population. Josh McDowell has estimated that maybe our evangelical youth are 10 percent better, Lord help us.

So at least it’s a measurable difference.

Well it is measurable, although there’s not so much hard [data] on that question as with some of the others. John Green, one of the best evangelical pollsters, says that about a third of all evangelicals say that premarital sex is okay. And about 15 percent say that adultery is okay.

Take the issue of racism. A Gallup study discovered that when they asked the question, “Do you object if a black neighbor moves in next door?” the least prejudiced were Catholics and non-evangelicals. The next group, in terms of prejudice, was mainline Protestants. Evangelicals and Southern Baptists were the worst.

Several studies find that physical and sexual abuse in theologically conservative homes is about the same as elsewhere. A large study of the Christian Reformed Church, a member of the nae, discovered that the frequency of physical and sexual abuse in this evangelical denomination was about the same as in the general population. One recent study, though, suggests that evangelical men who attend church regularly are less likely than the general population to commit domestic violence.

Materialism continues to be an incredible scandal. The average church member [from across the denominations] today gives about 2.6 percent of his or her income—a quarter of a tithe—to the church. Evangelicals used to be quite a lot better [in giving] than mainline denominations. But their giving has declined every year for several decades, and they’re now getting very close to the norm. The average evangelical giving is about 4.2 percent—about two-fifths of a tithe.

Six percent of the “born-again” people tithe; nine percent of evangelicals do. Our income has gone up fabulously over the last 30-plus years. The average household income now in the U.S. is $42,000-plus. If the average American Christian tithed, we’d have another $143 billion.

In an era in which people holding to traditional values appear to be returning to center stage in politics, your book says that all is not well with our day-to-day choices in the private realm. In effect, you’re accusing evangelicals of hypocrisy. Is that a fair conclusion?

I’m not doing that gladly. I’m doing that with tears in my eyes. We have to face the reality. It strikes me as being incredibly tragic and, yes, hypocritical for the evidence to show that precisely at a time when evangelicals have more political power to raise the issue of moral values in this society than they’ve had in a long time, the hard statistics on their own living show that they don’t live what they’re talking about. And sure, I’m afraid that’s hypocrisy. So we have to set our own house in order before we’re going to have either any integrity or any effectiveness in terms of helping the larger society recover wholesome two-parent families.

Has there ever been a time when the typical church has lived out the faith much better than now? Some might argue that this is just the nature of a sinful church before the Second Coming.

We don’t have polling data from the 1860s or the 1700s, so it’s hard to answer that question with precision. But as we look back over church history, we see that there has been ebb and flow, and that at times the church was especially unfaithful and full of disobedience and hypocrisy. At other times there was powerful renewal, and large groups of Christians were wonderfully transformed. There are stories from the Welsh Revival in which the prisons were essentially empty and not too many people went to pubs because there had been a radical transformation of large numbers of people.

To what historical era would you compare our own time?

If the question is evangelical obedience, then we’re certainly not in a time of revival.

How do we turn the ship around?

We need to rethink our theology. We need to ask, “Are we really biblical?” Cheap grace is right at the core of the problem. Cheap grace results when we reduce the gospel to forgiveness of sins only; when we limit salvation to personal fire insurance against hell; when we misunderstand persons as primarily souls; when we at best grasp only half of what the Bible says about sin; when we embrace the individualism and materialism and relativism of our current culture. We also lack a biblical understanding and practice of the church.

I would think that evangelicals would want to get biblical and define the gospel the way Jesus did—which is that it’s the Good News of the kingdom. Then we see that it means that the way to get into this kingdom is through unconditional grace because Jesus died for us. But it also means there’s now a new kingdom community of Jesus’ disciples, and that embracing Jesus means not just getting fire insurance so that one doesn’t go to hell, but it means embracing Jesus as Lord as well as Savior. And it means beginning to live as a part of his new community where everything is being transformed.

You’re pinning at least a good chunk of the blame on American individualism.

There’s no question that that’s at the core of it. We tend to reduce salvation to just forgiveness of sins. And in the New Testament, salvation means that, thank God, but it also means the new transformed life that’s possible in the power of the Spirit. And it means the new communal existence of the body of believers.

One of my favorite examples is the story of Zacchaeus. He is involved in social sin as a wicked tax collector. When he comes to Jesus, he gives away half his goods and pays back everything that he’s taken wrongly. Jesus says at the end of the story, “Today salvation has come to this house.” There’s not a word in the text about forgiveness of sins. Now, I’m sure Jesus forgave the rascal’s sins; he clearly needed it. But what the text talks about is the new transformed economic relationships that happen when Zacchaeus comes to Jesus.

Salvation is a lot more than just a new right relationship with God through forgiveness of sins. It’s a new, transformed lifestyle that you can see visible in the body of believers.

Obviously to be a disciple means there’s discipline. Do you see the neglect of church discipline in our day as a factor in this moral crisis?

It’s part of the larger question of recovering the New Testament understanding of the church. This culture is radically individualistic and relativistic. Whatever feels right for me is right for me; whatever feels right to you is right for you. That’s the dominant value. It’s considered outrageous for somebody to say somebody else is wrong.

But historic biblical faith understood the church as a new community. The basic New Testament images of the church are of the body of Christ, the people of God, and the family of God. All these stress the fact that we’re talking about a new community—a new, visible social order. That new community in the New Testament was living so differently from the world that people would say, “Wow, what’s going on here?” Jews were accepting Gentiles. The rich were accepting the poor and sharing with the poor. Men were accepting women as equals. It just astonished people because the church was so different from the world. It was countercultural.

Furthermore, [the New Testament church] understood that being a member of the body of Christ meant that you were accountable to each other. If one suffered, you all suffered. If one rejoiced, you all rejoiced. There was dramatic economic sharing in the New Testament, and there was church discipline. Jesus talked explicitly about church discipline in Matthew 18. Paul clearly had his churches live that out. All of the great traditions at the core of American evangelicalism, whether the Reformed tradition, the Wesleyan Methodist tradition, or the Anabaptist tradition, understood church discipline when they were strong and thriving. But very few evangelical churches these days have any serious appropriation and practice of church discipline.

Isn’t that at least in part because church discipline has been abused or become legalistic and mean-spirited?

Sure, that’s a part of it. But we don’t give up on marriage just because a lot of people have messed it up so badly. And we shouldn’t give up on church discipline just because we’ve so often done it in a legalistic way. We have to recover the New Testament understanding. John Wesley put it wonderfully when he said church discipline is watching over one another in love.

Today, when so many congregations are abandoning biblical truth, you say in the book that all congregations need to be connected to a denomination. Are you serious?

Absolutely. It’s simply wrong for a local congregation to have no accountability to a larger body. Now I’m not saying it has to be one of the current denominations. There can be new structures of accountability. Any congregations that feel they must break away from older denominations that are no longer faithful theologically or in terms of moral practice should be a part of some new denominational, organizational structure so they’re not isolated lone rangers. They need to have a larger structure of accountability. It is flatly unbiblical and heretical for an individual congregation to say, “We’ll just be by ourselves and not be accountable to anybody.”

What is the church doing right?

The small-group movement is a hopeful sign. One of the most important ways we develop mutual accountability in the local congregation is through small groups. It’s almost impossible to follow Jesus either in [matters of] sex and marriage or in money and helping the poor by yourself. You need the strong support of brothers and sisters. While the whole congregation should be like that, we need small groups to struggle with the specifics and talk about our struggles and get encouragement and prayer support. I wish every person in all of our churches with more than 50 members were in a small group.

What other things are contemporary evangelicals doing well?

Over the last 30 years, we’ve made significant progress in understanding that the mission of the church is both to do evangelism and to do social ministry. There’s also growing understanding that we can’t have a one-issue agenda as we get involved in public life. The recent National Association of Evangelicals declaration, “For the Health of the Nation: An Evangelical Call to Civic Responsibility,” explicitly rejects one-issue politics and says faithful evangelical political engagement will be based on a biblically balanced agenda. That means, yes, by all means, a concern with the sanctity of human life and with the renewal of the family. But it will also mean a concern for justice for the poor. It will mean concern for creation care, for human rights, and for peacemaking. We simply can’t allow right-wing or left-wing politics to provide the political agenda.

What areas are you personally working on?

Over the years I’ve needed to continue to work at making sure that my personal spiritual life is solid in terms of time for prayer and devotions regularly. That continues to be an ongoing challenge. I really, passionately want every corner of my life to be submitted to Jesus Christ and biblical truth. Living that out in terms of my money continues to be a challenge. Nothing is easy. But if we make that our resolve and ask the Spirit to transform us, I think wonderful things can happen.

Are you hopeful about the matters that you’ve written about? Or are you ready to give up?

I’m personally, by nature, something of an optimist. That may not come through clearly in this book, but I think it’s true. I’m genuinely enthusiastic by the renewal of the evangelical world in the last 50 years. It’s been a tremendous movement of change and growth since Carl Henry wrote The Uneasy Conscience of Modern Fundamentalism. There has been fabulous growth of evangelical colleges and seminaries, evangelical scholarship, evangelical churches. I pointed to the way that we’ve grown, I think, in understanding the mission of the church as being both evangelism and social ministry.

We’ve grown certainly in the number of evangelical agencies working with the poor. Fifty years ago World Vision was a Korean orphan’s choir. Now it’s a huge agency, and there are dozens of other evangelical multi-million-dollar relief-and-development agencies.

On some days I’m discouraged, and other days I think, Wow, the next few decades could be just fabulous. But what I’m sure about is that we won’t get close to the promise and the fulfillment of what’s possible unless we face head-on the scandalous way that we’re currently not living what we’re preaching.

Is it going to be the end of the evangelical movement if we don’t do something about these problems?

The Lord doesn’t take hypocrisy and disobedience lightly. He punishes, and there’s an inevitable kind of decline that sets in if you are hypocritical and don’t practice what you preach. It won’t happen instantly; our institutions are strong. But over a period of time it certainly will mean major decline.

I find it incredibly ironic that in the last few months, the importance of political life nurturing moral values and wholesome families and so on is center stage. And then you have this astonishing data that evangelicals live just like the world in terms of divorce. And it’s incredibly ironic that one of the issues—and one I agree vigorously with—is concerned with how public life affects marriage. I’m in favor of the marriage amendment. But at precisely a point in time when our political rhetoric as evangelicals has focused on that, we have to face the fact that we’re not any different from the world. And that’s just incredible hypocrisy and it undercuts our message to the larger society in a terrible way.

Copyright © 2005 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.