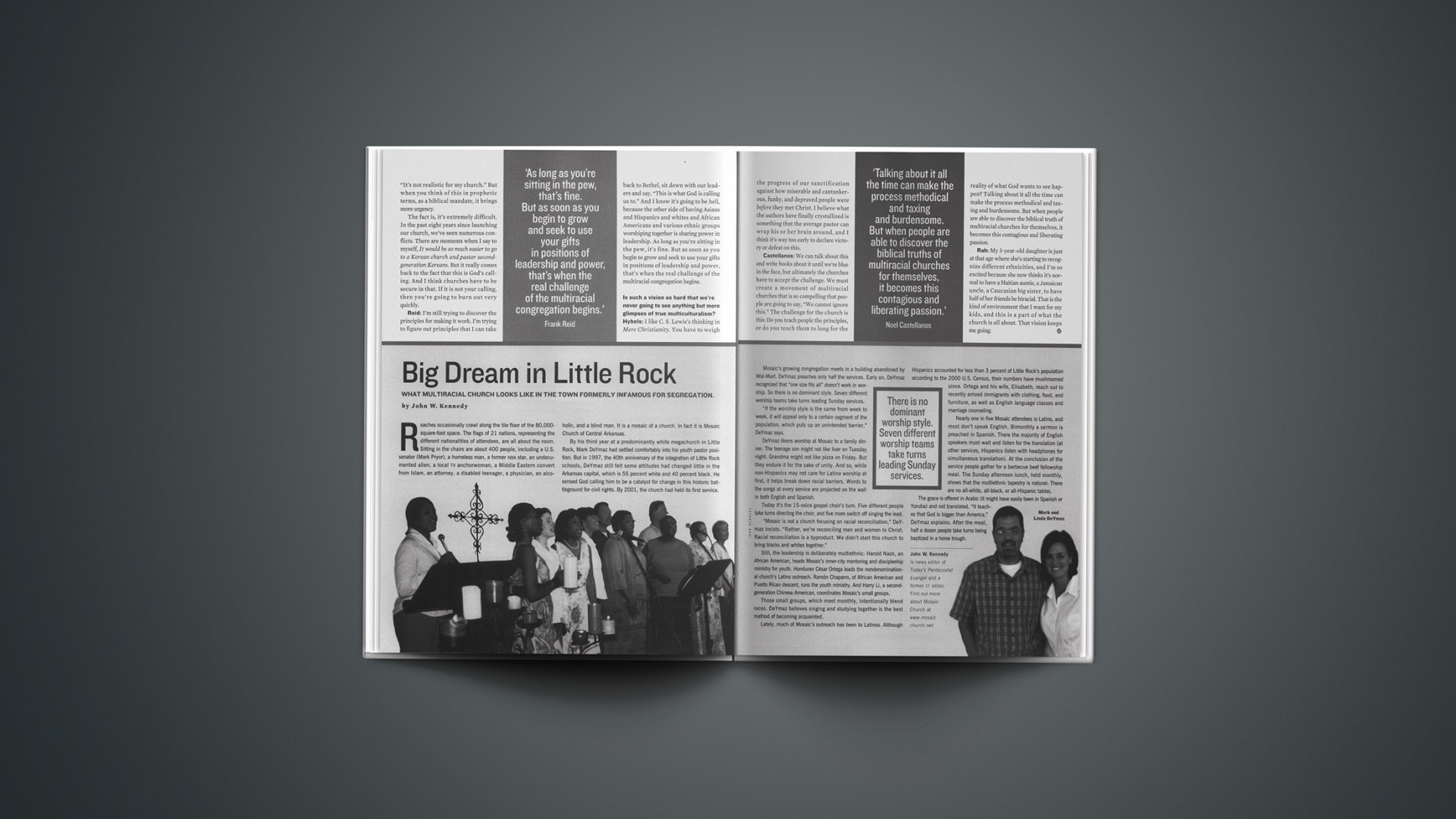

Roaches occasionally crawl along the tile floor of the 80,000-square-foot space. The flags of 21 nations, representing the different nationalities of attendees, are all about the room. Sitting in the chairs are about 400 people, including a U.S. senator (Mark Pryor), a homeless man, a former nba star, an undocumented alien, a local tv anchorwoman, a Middle Eastern convert from Islam, an attorney, a disabled teenager, a physician, an alcoholic, and a blind man. It is a mosaic of a church. In fact it is Mosaic Church of Central Arkansas.

By his third year at a predominantly white megachurch in Little Rock, Mark DeYmaz had settled comfortably into his youth pastor position. But in 1997, the 40th anniversary of the integration of Little Rock schools, DeYmaz still felt some attitudes had changed little in the Arkansas capital, which is 55 percent white and 40 percent black. He sensed God calling him to be a catalyst for change in this historic battleground for civil rights. By 2001, the church had held its first service.

Mosaic’s growing congregation meets in a building abandoned by Wal-Mart. DeYmaz preaches only half the services. Early on, DeYmaz recognized that “one size fits all” doesn’t work in worship. So there is no dominant style. Seven different worship teams take turns leading Sunday services.

“If the worship style is the same from week to week, it will appeal only to a certain segment of the population, which puts up an unintended barrier,” DeYmaz says.

DeYmaz likens worship at Mosaic to a family dinner. The teenage son might not like liver on Tuesday night. Grandma might not like pizza on Friday. But they endure it for the sake of unity. And so, while non-Hispanics may not care for Latino worship at first, it helps break down racial barriers. Words to the songs at every service are projected on the wall in both English and Spanish.

Today it’s the 15-voice gospel choir’s turn. Five different people take turns directing the choir, and five more switch off singing the lead.

“Mosaic is not a church focusing on racial reconciliation,” DeYmaz insists. “Rather, we’re reconciling men and women to Christ. Racial reconciliation is a byproduct. We didn’t start this church to bring blacks and whites together.”

Still, the leadership is deliberately multiethnic: Harold Nash, an African American, heads Mosaic’s inner-city mentoring and discipleship ministry for youth. Honduran César Ortega leads the nondenominational church’s Latino outreach. Ramón Chaparro, of African American and Puerto Rican descent, runs the youth ministry. And Harry Li, a second-generation Chinese American, coordinates Mosaic’s small groups.

Those small groups, which meet monthly, intentionally blend races. DeYmaz believes singing and studying together is the best method of becoming acquainted.

Lately, much of Mosaic’s outreach has been to Latinos. Although Hispanics accounted for less than 3 percent of Little Rock’s population according to the 2000 U.S. Census, their numbers have mushroomed since. Ortega and his wife, Elisabeth, reach out to recently arrived immigrants with clothing, food, and furniture, as well as English language classes and marriage counseling.

Nearly one in five Mosaic attendees is Latino, and most don’t speak English. Bimonthly a sermon is preached in Spanish. There the majority of English speakers must wait and listen for the translation (at other services, Hispanics listen with headphones for simultaneous translation). At the conclusion of the service people gather for a barbecue beef fellowship meal. The Sunday afternoon lunch, held monthly, shows that the multiethnic tapestry is natural: There are no all-white, all-black, or all-Hispanic tables.

The grace is offered in Arabic (it might have easily been in Spanish or Yoruba) and not translated. “It teaches that God is bigger than America,” DeYmaz explains. After the meal, half a dozen people take turns being baptized in a horse trough.

John W. Kennedy is news editor of Today’s Pentecostal Evangel and a former CT editor. Find out more about Mosaic Church at www.mosaic church.net.

Copyright © 2005 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

More about Mosaic Church of Central Arkansas is available from their website.

Harder than Anyone Can Imagine | Four working pastors—Latino, Asian, black, and white—respond to the bracing thesis of United by Faith. A CT forum with Noel Castellanos, Bill Hybels, Soong-Chan Rah, and Rank Reid

United by Faith is available from Christianbook.com and other book retailers.

More information is available from the publisher.

Our October, 2000, coverage of Divided by Faith includes:

Divided by Faith? | A recent study argues that American evangelicals cannot foster genuine racial reconciliation. Is our theology to blame? (Sept. 22, 2000)

Color-Blinded | Why 11 o’clock Sunday morning is still a mostly segregated hour. An excerpt from Divided by Faith. (Sept. 22, 2000)

We Can Overcome | A CT forum examines the subtle nature of the church’s racial division—and offers hope. (Sept. 29, 2000)

Shoulder to Shoulder in the Sanctuary | A profile in racial unity. (Sept. 28, 2000)

Common Ground in the Supermarket Line | A profile in racial unity. (Sept. 27, 2000)

The Lord in Black Skin | As a white pastor of a black church, I found the main reason prejudice and racism hurt so much: because we are so much alike. (Sept. 25, 2000)

More Christianity Today coverage of racial reconciliation includes:

Growing Up at Koinonia | The focus of a PBS documentary, Koinonia Farm was the target of segregationists, a radical Christian community, and where Jim Jordan grew up. (March 09, 2005)

The Work of Faith | How the torch of racial reconciliation, once carried by Christian civil-rights workers, is now being held by faith-based organizations. (Feb. 23, 2005)

Hope Deferred | Christians are uniquely positioned to further racial equality. (June 29, 2004)

CT Classic: Confessions of a Racist | It wasn’t until after Martin Luther King, Jr.’s death that I was struck by the truth of what he lived and preached. (January 17, 2000)

Martin Luther King, Jr.: A History | No Christian played a more prominent role in the century’s most significant social justice movement than Martin Luther King, Jr. (January 17, 2000)

CT Classic: The March to Montgomery | Christianity Today‘s coverage of King’s historic voting rights march, from our April 9, 1965 issue (January 17, 2000)

Catching Up with a Dream | Evangelicals and Race 30 Years After the Death of Martin Luther King, Jr. (March 2, 1998)

She Has a Dream, Too | Bernice King talks about her father’s death, her call to ministry, and what the church still needs to do about racism. (June 16, 1997)

Billy Graham Had a Dream | American revivalist preachers have been evangelical Christianity’s most visible spokesmen over the centuries. What does their record on race relations show? (Jan. 12, 1998)