|

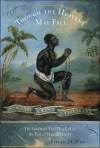

Stephen M. Wise, veteran animal-rights lawyer, finds inspiration in the 18th-century antislavery activist Granville Sharp. And Christians who want to act effectively against contemporary slavery in Mali, sexual bondage in Cambodia, and religious persecution in North Korea need to study this father of evangelical social reform. The dogged intolerance of Granville Sharp in his pursuing the abolition of slavery is a lesson in the social impact of true religious commitment and the virtue of persistence.

Between the years of 1765 and 1772, Sharp advised and aided four different African slaves who wanted to claim their rights as human beings. In the first case, Sharp was visiting William, his physician brother, who treated sick paupers ever morning. At his brother’s surgery he encountered Jonathan Strong, who was nearly dead: “feverish, nearly blind, doubly lame, ‘ready to drop down.'” The young black’s master had struck him repeatedly on the head and cast out into the street to die. Granville persuaded William to admit him to hospital and then found him employment as a delivery boy for a pharmacist. When Strong’s former master saw him in the street one day, he decided to reclaim his “property” and had him held in a local prison pending his shipment as a slave to Jamaica.

Strong had been baptized since he had last seen his master, so he now sent a frantic message to his godparents and then to his employer. His employer contacted Granville Sharp. Sharp immediately arranged for a hearing on the legality of Strong’s imprisonment. The Lord Mayor of London presided, found no cause for Strong’s detention, and freed him, whereupon—right there in the presence of the Lord Mayor—his enemies grabbed him and began to drag him away. Sharp charged them with assault, and the villains skulked off.

The Jonathan Strong matter was not settled. The man who had purchased Strong from his master sued the brothers Sharp. The case brought against them was a mess, but the Sharps’ lawyer advised them to settle out of court because they were up against was a 40-year-old legal opinion that seriously undercut their defense.

Can Christians be slaves? The so-called Joint Opinion was, in fact, not law, but an informal opinion produced by two eminent legal officials under the influence of much food and drink and the convivial pressures of a group of West Indian planters. These economic interests lobbied the key legal minds to undercut two popular ideas that had been threatening the slave economies of the British Empire.

One idea was religious: that baptism automatically conferred freedom on slaves. The Hebrew Scriptures had set a kind of precedent. In Leviticus, the Lord had instructed the children of Israel not to enslave one another, but to buy the children of the strangers that sojourned around them. Some people applied this to the Christian nations of Europe and claimed that Christians could not enslave Christians. The heathen, on the other hand, were fair game.

But what if those heathen became Christians? Despite the fact that English courts had never actually freed a baptized slave, most blacks and many whites believed that baptism did indeed confer freedom. (Obviously, such a notion discouraged masters from teaching their slaves the Christian faith.) Plied with much wine, the two legal experts declared that baptism did not affect a person’s slave status.

The other idea was political: that the air of England conferred liberty on all who breathed it. The notion derived in part from a 1569 case in which an English court freed a Russian slave, saying, “England was too pure an air for slaves to breathe in.” The popular mind had been infected with such notions of liberty from the day King John signed the Magna Carta.To this notion, too, the well-wined legal experts said their nay.

Sharp was not about to give in, and the brilliant autodidact began to study the law for himself in order to refute the Joint Opinion. Strong stumbled on the eminent Sir William Blackstone’s approving citation of a 1701 slave case: The English “spirit of liberty is so deeply implanted in our constitution, and rooted in our very soil, that a slave or Negro, the moment he lands in England, falls under the protection of the laws, and with regard to all natural rights becomes so eo instanti a freeman.” Elsewhere, Blackstone called the “absolute and unlimited power … given to the master over the life and fortune of the slave … repugnant to reason and the principles of natural law.” (Blackstone blunted his language in later editions of his Commentaries.)

Sharp wrote up his own legal arguments against slavery in A Representation of the Injustice and Dangerous Tendency of Tolerating Slavery, or Even of Admitting the Least Claim to Private Property in the Persons of Men, in England, and sent it around to lawyers who would be arguing slave cases.

Courtroom drama Sharp took on two more test cases: First, John Hylas, a former slave whose slave wife had been taken from him and sent back to slavery in the West Indies. And second, Thomas Lewis, a black who was kidnapped and put aboard a ship bound for Jamaica where he was to be sold as a slave. In both cases, the court ruled in favor of the blacks, but each time the verdict was framed too narrowly to set a precedent that would undermine the institution of slavery. That would have to wait for his next case—Somerset vs. Steuart.

James Somerset was an escaped slave. He had served his master, Charles Steuart in the Americas, but two years after arriving in England with Steuart, Somerset left him. Steuart was enraged and sent the slave-catchers after him.

The ensuing legal case featured several familiar actors: The barrister who had spoken against slavery in the Lewis case was now representing the pro-slavery Charles Steuart. Lord Mansfield, who had presided over the Lewis case was to judge this one as well. He was one of the most respected legal minds in England, and was something of a reformer, known for defending the rights of Catholics and non-conformists at a time when non-Anglicans suffered serious discrimination. And Granville Sharp took an interest in Somerset’s case—as did slave-holding business interests from the West Indies. Money flowed from their coffers to Steuart, while principled anti-slavery lawyers did pro bono work for Somerset. Because Sharp was afraid he had antagonized Lord Mansfield in the Lewis case, he stayed in the background.

The case turned on several questions, including whether colonial laws had any validity in England. The legal arguments will sound familiar to those watching the advance of gay marriage today. All agreed that English law recognized a marriage from a foreign country—say Turkey. But if a man from Turkey brought multiple wives to England, he would be the target of a criminal prosecution. Did a slave’s status in Virginia make him a slave in England? Or was slavery so odious to English notions of liberty that it was akin to polygamy?

Readers who enjoy a good courtroom drama will want to read Wise’s summary of the arguments and tactics used by both sides. Ultimately, Lord Mansfield undercut the pro-slavery arguments by expressing serious doubt about the infamous Joint Opinion. Steuart’s barrister was left nearly speechless. In Wise’s words, “The West Indies representatives who were paying [the barrister’s] substantial fees … must have choked on their sugar cane.”

Lord Mansfield had been hoping for another narrow decision, but both parties had intended to make this a test case, and so he declared that, absent a positive law that established slavery (as it did in the colonies), “black chattel slavery was ‘of such a nature … so odious’ that English common law would never accept it.”

Mansfield later tried to play down the significance of his decision, but it could not be contained. It reverberated throughout England and the colonies. And in the course of time, its principles undercut the slave trade as well.

Sickened by the violence of the American revolution, Sharp resigned from his job in the Ordnance office and pursued antislavery, prison, and hospital reform movements while living off the generosity of his brothers. He joined with Wilberforce and others to form the Society for the abolition of the Slave Trade. And before he died, he was awarded honorary doctorates by Brown, Harvard, and William and Mary.

Despite Sharp’s great achievement, Steven Wise seems put off by the original abolitionist, calling him “harsh, absolute, moralistic, and unforgiving.” “Sharp’s personality had an ugly, intolerant side,” Wise writes, and labels Sharp “a religious bigot.”

Granville Sharp’s bigotry (anti-Catholicism, anti-Quakerism) is unremarkable for his time. And his belief that blacks were intellectually and morally inferior to whites was conventional wisdom shared by other great minds of the time: Voltaire and Jefferson among them.

Granville Sharp was both a man of his times and a man ahead of his times. But perhaps religious fervor is the best fuel for the reform of social evils.

David Neff is editor of Christianity Today.

Copyright © 2005 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.