Sin seldom strides into our lives announcing its hostile intentions. It prefers stealth, camouflage, or even better, to appear friendly. As Thomas Aquinas taught, when we do evil we always will to act “under the aspect of the good.”

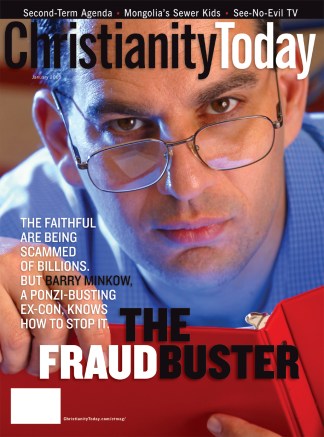

Sin typically cloaks itself in some story or rationalization that mitigates or hides our wrongdoing from ourselves: Inordinate anger masquerades as “righteous indignation,” arrogance as “standing up for my rights,” retaliation as “giving them what they deserve,” profligacy as “giving myself what I deserve,” lust as “healthy romantic ardor,” and so on. When it comes to sin, we’re inveterate “spin doctors.” As “The Fraudbuster” suggests, such rationalizations also accompany greed.

Greed is an inappropriate attitude toward things of value, built on the mistaken judgment that my well-being is tied to the sum of my possessions. Greed is more than mistaken belief—as if knowing a few more facts would somehow solve the problem. It also involves emotions (perhaps longing, unfulfillment, fear) and attitudes (a sense of entitlement, rivalry). Greed alienates us from God, from our neighbor, and from our true self.

Ahab only coveted Naboth’s vineyard in his heart—one form of greed. But Jezebel, his queen, acting under the banner of entitlement—”Are you the king of Israel or not?” (1 Kings 21:7, nlt)—arranged for Naboth’s death and seized the vineyard. When we covet our neighbors’ house, car, spouse, or whatever else, we see them as rivals or impediments to our own gratification.

On one level, we see at once the errors that underlie greed. We know that the world and all that it contains belong to God, and that our immediate and ultimate good consists in being rightly related to him, not to any of the things his world contains. Nevertheless, disordered loves and skewed thinking combine to suppress this clear Christian truth. So we pursue goods to bolster our egos, to win the admiration and acceptance of others, to dominate others, or to palliate unacknowledged spiritual ills.

How we camouflage greed depends on the particular species of greed to which we’re tempted. For instance, greed can take the form of acquisitiveness—being inordinately concerned with amassing goods.

Michael Milken, the infamous junk-bond king of Drexel Burnham Lambert, earned a salary of $550 million per year when he was indicted and eventually convicted for violating federal securities and racketeering laws. Although rich beyond the average person’s wildest imagination, Milken craved more and cheated to get it—a clear case of acquisitiveness. What might have motivated him? Perhaps he cloaked his acquisitiveness by ambition and ego, and justified his excesses by supposing that only unbridled competitiveness could win the high regard of his adversaries and success in the world of high finance.

Saint Drexel

Compare Milken with Katherine Drexel, niece of Anthony J. Drexel, the financier whose name Milken’s former company still bears. Katherine, only the second American citizen to be canonized by the Roman Catholic Church, inherited millions from the family’s banking fortune. She did what the rich young ruler of the Gospels could not: She sold all that she had and gave it to the poor. Despite her wealth, she lived poorly, mended her own clothes, traveled by third-class rail, and distributed millions to more than 200 missions and schools established on behalf of Native Americans and African Americans. Milken was in the grip of greed; Katherine Drexel let money slip easily from her grasp.

Just here, however, we of the middle class must be on our guard. As we back the Camry out of the driveway of our comfortable suburban home, we congratulate ourselves that we are not like Milken. (“Thanks be to God that I am not like that sinner.”) And as for Drexel, well, that’s a fanatical extreme to which normal Christians aren’t called. And so, by the clever use of false comparison groups, we emerge morally in the clear, our own tendencies to greed successfully explained away. But our job is not simply to be better than Milken, but to conform fully to the image of Christ, whatever that may demand of us. And while it’s true that not all of us are called to emulate Francis of Assisi and Katherine Drexel, some of us may be, and to dismiss such generosity as a fanatical extreme may close us off to the way God wishes to work in our lives.

Greed can also take form as stinginess—being too reluctant to part with one’s goods. Just as one can be rich or of modest means and be generous, so one can be rich or poor and be tight-fisted. Fear may be a motivating factor. Recall Scarlett O’Hara’s oath shouted before God with a clenched fist: “As God as my witness, I’ll never be hungry again.” Her fear of not having enough hardened her in a career of calculated greediness.

Other rationales may motivate stinginess. As you walk down the bustling city street a beggar chinks his cup of coins in your direction, asking for a handout. You quicken your pace, avoid eye contact, give the beggar wide berth, and succeed in not parting with a dime. And as you hasten on you may mollify a twinge of conscience by saying, “I’m doing him a favor by not reinforcing his panhandling ways.”

Yes, there are con men in the world, though persons reduced to begging for pocket change are often among the genuinely poor in spirit. The problem is that our indifference to the plight of the poor easily becomes a settled state of the will, which we justify by oft-heard rationales: These people are shiftless and lazy; they will only squander what is given; I don’t want to reinforce a welfare culture, and so forth. Christians, however, are commanded “to be rich in good deeds, and to be generous and willing to share” (1 Tim. 6:18). If sharing should be the default mode for Christians, then if most of us aim wide of the mark by being “hair-trigger” givers, we’ll probably come close to hitting the target.

When Good Stewardship Is Bad

Most insidiously, greed sometimes masquerades as a Christian virtue. A Christian college hired a friend of mine to teach, deliberately calculating his course load at a fraction less than what was required for him to receive benefits. His department chair protested to the administration, but they told him that it was simply a matter of good stewardship not to pay more than the market would bear. When the professor took ill that same year and was hospitalized, he could not pay his medical bills.

The churches that fall prey to fraud may have justified their investments by saying they did not want to bury their talents. In the name of good stewardship, they suppressed the critical faculties that usually tell us “if it sounds too good to be true, it is too good to be true.” Perhaps they cast an envious eye on the nearest megachurch and reassured themselves that lavish budgets and huge physical plants are God’s preferred way of showing his favor. In an extreme form, Christian justifications for greed lead to a “name it and claim it” gospel of prosperity that inverts the Gospel teaching about camels, needles, rich persons, and heaven.

No matter its face (and there are many more than three), greed’s grip and the attitudes that reinforce it are not inescapable. The church has developed a rich repertoire of spiritual exercises designed to help us. Confess greed. Pray that the Holy Spirit would illumine the eyes of your heart to discern greed’s stealthy approach. Contemplate your death, for he who dies with the most toys still dies. Practice a Lenten discipline that requires you to go without some customary luxury. Serve in a soup kitchen, build a home with Habitat for Humanity, or visit shut-ins living off Medicare. These exercises, and a myriad like them, have the effect of Nathan’s story on David; they unmask our pretensions and shine a true light on our character and deeds.

W. Jay Wood is professor of philosophy at Wheaton College in Wheaton, Illinois. He is author of Epistemology: Becoming Intellectually Virtuous (InterVarsity).

Copyright © 2005 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

The Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament continue Katharine Drexel’s work of giving to the poor. The are currently building a shrine to her.

Greed, by Phyllis A. Tickle, is available from Christianbook.com and other book retailers. Greed and other books on the seven deadly sins are reviewed in: Mistakes Were Made | Four of the Seven Deadly Sins, as seen from a contemporary vantage point. (March 22, 2004)

Christianity Today‘s recent cover story on fraud includes:

The Fraudbuster | The faithful are being defrauded of billions. But this Ponzi-busting ex-con knows how to stop it. (Dec. 17, 2004)

Success in Failure | Barry Minkow builds his ministry on what’s gone wrong. (Dec. 17, 2004)

Stop Fraud Before It Starts | Barry Minkow says every investor should get the answer to four questions before investing. (Dec. 17, 2004)

More Christianity Today articles on greed include:

A Case Study in Greed | The Tao of Enron takes lessons from the second-largest bankruptcy in American history. (April 01, 2003)

The Profit of God | Finding the Christian path in business. (Jan. 27, 2003)

Bad Company Corrupts | Michael Novak, theological champion of the free market, reflects on what recent business scandals mean for church and state. (Jan. 27, 2003)