Click here for Photo Essay: Click here for Audio Clips |

Shortly after dawn, before the scorching sun rises high enough to stop most travelers in their tracks, Muridi Mukomwa holds his toddler as he trudges across the African plains. His wife, Halima Husseini, carries their youngest child on her back. Friends and relatives take turns lugging the family’s duffle bag that contains all of their possessions. Their entire village walks with them to a nearby dirt airstrip to say good-bye. Perhaps they will be reunited in America, they comfort one another. “Inshallah” (God willing), is the repeated reply.

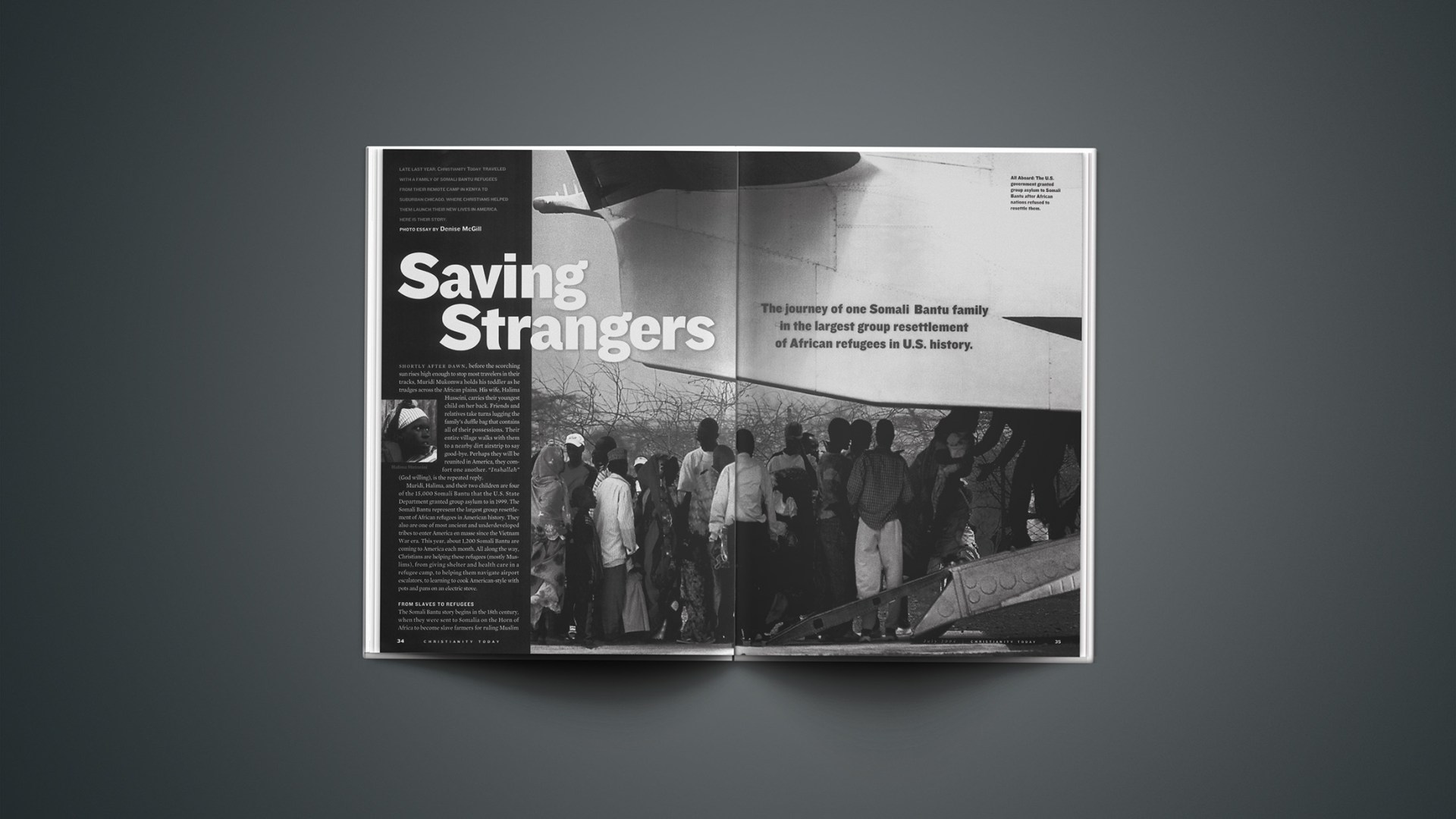

Muridi, Halima, and their two children are four of the 15,000 Somali Bantu that the U.S. State Department granted group asylum to in 1999. The Somali Bantu represent the largest group resettlement of African refugees in American history. They also are one of most ancient and underdeveloped tribes to enter America en masse since the Vietnam War era. This year, about 1,200 Somali Bantu are coming to America each month. All along the way, Christians are helping these refugees (mostly Muslims), from giving shelter and health care in a refugee camp, to helping them navigate airport escalators, to learning to cook American-style with pots and pans on an electric stove.

From slaves to refugees

The Somali Bantu story begins in the 18th century, when they were sent to Somalia on the Horn of Africa to become slave farmers for ruling Muslim clans. Over the generations, a large number of Bantu slaves converted to Islam, which secured their freedom since the Qur’an forbids Muslims from owning other Muslims. But the slave label continued to dog the Somali Bantu. Those who were free were segregated deep in Somalia’s southern interior, living in primitive huts as they worked their fields. The few who had access to education were denied skilled jobs. Even by African standards, they were destitute. Some Africans, especially ethnic Somalis, despised them.

In 1991, Somali clan warfare broke out and with it, the first stages of anarchy. Bandits robbed Muridi’s family of sesame, corn, and mangos. “When the civil war broke out, everyone was hungry,” Muridi says. Several hundred thousand Somali villagers fled. Muridi and his father once walked 60 miles foraging for food; the only thing they found to eat was raw sugar cane. But it was enough for their family to survive.

In the 1990s, Somalia slipped into brutal lawlessness as dramatized in journalist Mark Bowden’s nonfiction bestseller, Black Hawk Down. Since that time, there has been no central government in Somalia. Where there was once a nation-state, there are now only warlords who break peace agreements as often as the tide rolls out to the Indian Ocean.

When the United States and United Nations troops left Somalia, Muridi’s life took a drastic turn for the worse. He explains, “Everyone took his gun. And us? We don’t have a gun.” Nor did they have protection from any of the powerful clans. They were easy prey for further violence.

One day, Muridi was away from home on an errand when a Somali warlord’s militia swept through the Bantu village burning homes, raping, and killing along the way. Muridi fled and made it to safety, but he never saw his parents again. He was 16 years old, and all that was familiar had been stripped away.

‘Sometimes we never even had water. We didn’t have enough food.’ Halima on her experience in the Kakuma refugee camp in northern Kenya

Camp life’s cruel realities

Following hundreds of thousands of Somali Bantu and others who flowed into Kenya like migrating herds, Muridi reunited with a brother and an uncle in the squalor of the Dadaab refugee camp.

Food was scarce. Violence, starvation, and the death of newborns were common. But Muridi came to manhood and steered clear of most trouble. Occasionally, he found work as a janitor. He let his uncle find a bride for him. “Halima? She is good,” Muridi says, describing his arranged marriage. “Even I have two children from her. How can I leave her? I love her so much. Halima, she’s my wife.”

Halima’s family also fled Somalia when she was very young, and she has no memory of the trip. But she and her children, like half the Somali Bantu, have no memory of anything but exile. She is tiny—100 pounds of lean muscle. Gaining much weight in a refugee camp is unheard of. Daily survival requires the hard labor of hauling water and firewood. “That’s how we lived,” she now says. “Sometimes we never even had water. We didn’t have enough food.” The U.N.’s World Food Program rations made the difference between life and death. “We had no money so there was no food. We just had the food the white people give us. Just corn; we used to eat that.”

But even in the camps, Somali Bantu suffered discrimination from other refugees. They endured violent attacks more than other ethnic groups. In time, relief workers uncovered their plight, and the United Nations High Commission on Refugees (UNHCR) now recognizes them as a minority at-risk population.

Eventually, many Somali Bantu, including Muridi and Halima, relocated to Kakuma, another sprawling camp of 60,000 on the Kenya-Sudan border. Many Somali Bantu made the best of their situation, attending classes and working at meager jobs. They elected elders to represent their interests with aid organizations, their first taste of self-determination. Traditionally moderate Muslims, they resisted pressure to join extremist sects. Though they have been a small group within the refugee camp, they held a majority of the manual labor jobs. They quickly gained a stellar reputation among international aid workers.

Pius Sefu, a project manager for World Vision at Kakuma, says, “I find the Somali Bantu very industrious. Have you looked at the cleanliness of that place?” The Somali Bantu have made their own bricks to build extensions onto their houses, decorated their homes with intricate whitewash designs, and dug irrigation to grow gardens in an otherwise arid wasteland. “That’s unique to the Somali Bantu,” Sefu says.

While many ethnic Somalis look forward to returning to Somalia when peace returns to their nation, the Bantu know they cannot go back. It was never really their home. In 1997, the UNHCR began negotiations to resettle the Somali Bantu to ancestral homelands in Mozambique and Tanzania. Burdened with their own internal problems, both nations backed away from the idea.

In 1999, the Clinton administration offered asylum to all Somali Bantu who had agreed to resettle in Africa. A long process ensued to verify exactly which refugees qualified. Applicants had to prove that they were indeed Somali Bantu and that they had been persecuted in Somalia.

Halima’s family fled Somalia when she was very young, and she has no memory of the trip. But she and her children, like half the Somali Bantu, have no memory of anything else but exile.

The U.S. government’s offer turned out to have an astonishing price tag. By the end of August 2001, the Bantu finally were ready. But the September 11 terrorist attacks changed everything. With new security risks, Americans could not safely visit refugee camps to conduct immigration interviews. All Somali Bantu had to be re-verified to ward against infiltrators. The men also had to prove they were not a security threat to Americans. The only way the State Department could honor its offer and maintain U.S. security was to set up a new, secure processing office and move the Somali Bantu to a safe holding site until they migrate. To do so, the State Department expects to spend $50 million for staff, security, and supplies in one of the world’s least hospitable places.

The U.S. government has a revolving fund to transport the refugees to their new homes in America. The fund pays for tickets to America, $850 per adult, and refugees have three years to repay it, interest free.

Mobilizing for America

Deep inside the Kakuma camp, Issa Abdullahi Mberwa stands at a chalkboard in a covered pavilion before 16 benches filled with women nursing their babies. The board is littered with the day’s lessons: “Walk. Don’t walk. Stop.” He lectures on traffic lights to women who may not see a single motor vehicle for days at a time.

The class reads in unison as gritty dust blows through the students’ headscarves.

What is your address?

“4501 Mason Street,” they chant.

What do you do if your house is on fire in the United States?

“9-1-1!”

The Somali Bantu are mobilizing for America. Until recently, most of these women had never held a pen, let alone written their name. Many couldn’t say the days of the week in any language. Instructor Mberwa asks one student her name and marital status. But she stares at the floor. He coaxes an answer from her and encourages eye contact, telling her that she must practice speaking to men and strangers. Her new life demands it.

Elders require every man, woman, and child to attend English literacy classes. Adults who didn’t know their own age can now tell time and write the alphabet.

In America, “Everything involves reading,” says Mohamed Awers Juma, an elected community elder. “Even a door has a sign that says ‘Open.’ “

The Somali Bantu have about a 200-year technology gap to fill just to live in an American house.

“We are making a lot of efforts to get literate,” Juma says. Still, it’s a long road from holding a pen to landing a decent job.

“Bantus are not used to being idle. We are a people of work,” Juma says. The biggest question he and other Somali Bantu ask is whether they will find jobs in America. “We don’t want to be idle a single day. We want to work.”

From Kakuma to O’Hare

Muridi was among the first wave within his tribal extended family to journey to America. In late November, he lands at Chicago’s O’Hare Airport with two kids, one wife, and no checked bags. His first gift in America is a winter coat.

Ryan Smith, resettlement director for World Relief in suburban DuPage County, welcomes the family at O’Hare along with three middle-aged women offering smiles and baby blankets. The trio comes from the human concerns committee of Bethel United Church of Christ, the church in suburban Elmhurst that sponsored the Mukomwa family.

The Mukomwas’ first cultural challenge occurs as they exit the airport and approach a minivan. Eleven-month-old son Mussa has lived his whole life in a sling strapped to his mother. Whenever he fusses, she breast-feeds him. Somali Bantu infants rarely cry. They rarely need to.

It takes several volunteers to help navigate the sliding door. Then the seatbelt. Then the child carrier. Little Mussa screams. The 30-minute ride to their new home may be the longest he has ever been separated from his mother. His parents have just entered the Promised Land, and their child who never cries is crying out, and they can’t help him. His 2-year-old brother joins the cacophony.

They all arrive at the lovely suburban home of John and Jane Stoller-Schoff, members of St. Mark’s Episcopal Church in Geneva, Illinois. As they unload in the driveway, their eyes drink in the unfamiliar surroundings: A suburban brick two-story home complete with a sport utility vehicle and a trampoline. For the next 10 days, this is America.

World Relief’s Smith says the Somali Bantu have about a 200-year technology gap to fill just to live in an American house. “They learn that in a couple weeks,” he says, and the best way is for an American family to teach them.

But the next few days prove daunting for both families. The Mukomwa family sleeps in their winter coats, but leaves the house wearing sandals. The couple stares blankly at the abundance of housewares American Christians put at their feet, more material possessions than they could have imagined ever owning. Muridi and Halima are deathly scared of the family’s tiny dog, obliging the Stoller-Schoffs to restrain their much-loved pet. Within 72 hours of her arrival, Halima is bedridden with homesickness. On day four, the parents, unable to consume American-style food, refuse all food except chicken and rice.

“I feel dizzy,” Halima says through an interpreter. “My heart was getting pulled. I couldn’t even breathe. When I couldn’t see my mother the first night, I woke up. But I couldn’t move my legs. I couldn’t feel them at all.”

But as day five dawns, the Mukomwas have a breakthrough. Halima counts to ten in English, and her toddler son discovers Teletubbies. She conquers the washing machine and sees snow. Day eight is Thanksgiving, and they eat platters full of turkey and potatoes. They decline the cranberry sauce.

A week after their arrival, still in the throes of culture shock, Muridi admits that no class in Kenya could have fully prepared him for American life. When he arrived, he didn’t know how he would get the bare necessities. “I move with one bag. I have only clothes and shoes,” he says. “I don’t have money. No money. Total no money.”

“First of all, I was worrying about clothes for my children,” he adds. “It is not possible to count, now I have so many. Also, I have clothes, and also my wife. Now I think only one thing remains—to know something and to learn, and to find a job.”

World Relief’s Smith couldn’t agree more. To get started in America, the Mukomwas receive help in a patchwork of public assistance and faith-based outreach. All are designed to carry them for about four months, allowing the adults to concentrate on becoming employable.

Ten agencies in the United States, including World Relief, are charged with the Somali Bantus’ sustenance and success here. To accomplish this, World Relief partners with churches to help integrate immigrants into American society. When a church like Elmhurst’s Bethel UCC wants to sponsor a family, they are advised to budget $5,000 for a family of four. These funds help cover rent, medical help, and startup costs like dishes and diapers.

But World Relief’s goal is for refugees to become self-sufficient. “We want churches to give, but give wisely,” Smith explains. “They’re helping a family up on their feet, then letting the family walk on their own.” He says the challenge is on the front end, in the first few years. More than half the Somali Bantu are under age 10, such is their high birth rate and short life expectancy. Most will attend school and be fluent in English in a couple years.

“They’re going to be Americans,” he says. “Just look at these kids. Their future is unlimited.”

Denise McGill is a writer and photojournalist from Ohio.

Audio Clips

How to Help a Refugee

|

Hear stories of refugee resettlement. Jane Stoller-Schoff shares how her own family was changed by hosting refugees in her Chicago-area home. Click here Muridi Mukomwa tells his story about being a refugee for more than 10 years. Click here Osman Mussa Mganga describes life for refugees in their desolate camp in northern Kenya. Click here The Somali Bantu will resettle in about 50 cities across the United States. Five national faith-based agencies are helping with their arrival. These groups are responsible for providing all essential services during the first 30 days a refugee is in the United States. Most agencies continue to advise refugees or make referrals for at least six more months. Visit their websites to find an office near you and learn ways to become involved. World Reliefwww.wr.org/how_can_i_help/volunteer/us_ministries.asp. Or, call Beth 443-451-1990 Church World Serviceswww.churchworldservice.org/Immigration/affiliates.html. Or, call Thomas Abraham 212-870-2815 Episcopal Migration Ministrieswww.episcopalchurch.org/emm/. Or, call Rev. John Denaro 212-716-6057 Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Serviceswww.lirs.org/What/partners/affiliates.htm. Or, call Susan Baukhages 410-230-2791 U. S. Catholic Conference—Migration and Refugee Services www.nccbuscc.org/mrs/refprog.htm. Or, call 202-541-3352 |

Copyright © 2004 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

Also posted today is Inside CT: Bike Rides with Refugees

Other Christianity Today articles from Somalia include:

Split Families in Limbo | Relief agencies push Bush to reverse sharp decline in refugee resettlement program. (Dec. 13, 2002)

Yemen Court Sentences Somali Convert To Death | Former Muslim given one week to recant Christianity or face execution. (July 7, 2000)

Somali Convert in Yemen Transferred to Immigration Jail | U.N. agency proposing emergency resettlement for Christian convert from Islam. (July 21, 2000)

Somali Convert Released From Jail in Yemen | Reunited family en route to New Zealand. (Aug. 29, 2000)

Freed Somali Christian Arrives in New Zealand | ‘It was God who saved me,’ Haji declares. (Sept. 6, 2000)

Other Christianity Today articles on refugees include:

Before the Refugee Dam Breaks | Agencies prepare to help up to 900,000 people in Iraq War. (April 24, 2003)

Churches Demolished at Sudanese Refugee Camp | Bulldozers raze prayer centers as part of government “re-planning” exercise. (Dec. 30, 2003)

Leaders Press for Refugee Asylum | Christians demand Australian government show compassion. (Oct. 17, 2001)

Finding Homes for the ‘Lost Boys’ | They’ve seen their parents shot, their villages burned, and their homeland recede in the distance as they escaped. Now these Sudanese youth build a new life in suburban Seattle. (July 20, 2001)

Ministries Intensify As East Timorese Refugee Camps Grow | Evangelicals working furiously to meet physical and spiritual needs (Dec. 6, 1999)

Coming to a Neighborhood Near You | Refugees from around the world are knocking on our door. (July 12, 1999)