When we floated some topic ideas for future issues of Christian History & Biography to our readers at www.christianhistory.net last year, our suggestion of “Phoebe Palmer and the American Holiness Revival” elicited a resounding “Huh?”

This was all the excuse we needed. This was one of those cases of someone almost unknown today, who actually left a Rushmore-sized impression on America’s religious landscape.

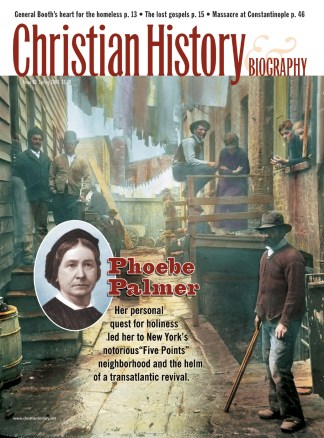

Phoebe Palmer was the most influential woman in the largest, fastest-growing religious group in mid-19th-century America—Methodism. By her initiative, missions were begun, camp-meetings instituted, and many thousands attested to the transforming power of divine grace. She mothered a nationwide movement that birthed such denominations as the Church of the Nazarene and the Salvation Army, bridged 18th-century Methodist revivalism to 20th-century Pentecostalism, and pioneered in social reform and female ministry.

And these are only a few parts of her compelling life story, which in turn is only one part of the wider story of the American holiness revival.

That larger story explains why, for example, the great evangelist D. L. Moody, nearing the end of this life, told his lieutenant R. A. Torrey to preach “the baptism of the Holy Spirit” above all else. It explains how such non-Wesleyans as Moody and Torrey used that electric phrase in a transitional sense—somewhere between an early Methodist meaning (an experience that brought a person to a new plane of holy living) and a Pentecostal meaning (a Spirit-empowerment signalled by speaking in tongues and other extraordinary spiritual gifts).

The holiness kaleidoscope

Through the holiness movement, a high proportion of 19th-century American Christians, and a hefty chunk of the 20th- and 21st-century church too, have been touched in some way by teachings about “Christian perfectionism”: Wesleyans (Palmer) and Reformed (the Keswick movement); Quakers (Hannah Whitall Smith), Baptists (A. B. Earle), and Congregationalists (Charles G. Finney); mystics (Thomas Upham), urban missionaries (the Salvation Army), and abolitionists (the Wesleyans and Free Methodists); respected evangelists (D. L. Moody) and fringe utopians (John Noyes)—all drew from the 18th-century teachings of John Wesley and reinterpreted them through the 19th-century tradition of revivalism.

Throughout Christian history, from the martyrs and monastics to the Puritans and Pietists, movements have arisen in pursuit of a deeper devotion and more active Christlikeness. So it was in 1837 when, fresh from a personal tragedy and a transforming experience of “entire consecration” and “entire sanctification,” Phoebe Palmer struck out from her comfortable New York home to do whatever the Lord demanded of her.

It turned out this included ministering to Methodist bishops in her parlor, launching benevolent missions in the worst slums of New York, mobilizing an army of lay evangelists, writing impassioned biblical arguments for women in ministry, and preaching on two continents. And as she did these things, she helped launch a revival that changed a nation.

To everyone she met, Palmer brought a message that if one consecrated oneself entirely, believed the Bible’s promises of a new empowerment to live a holy life, and asked for the grace to live that life, then one could truly testify to “entire sanctification” or holiness of heart and life. And Americans responded by the thousands, testifying as she did.

Love in the modern world

What was it about the holiness teachings of Palmer and others that appealed to such a large, diverse constituency? We need to peer inside their social world to see why these Victorian Christians felt so passionately about the potential for a “higher Christian life.”

In the competitive, upwardly mobile world of mid-19th-century northeastern cities, thousands were seeking a closer walk with their Lord. Many of them had moved into the northeast’s business and commercial centers from the small towns and farms of what had only recently been frontier land.

Especially as the Victorian era entered its most prosperous phase around the time of the Civil War, many felt alienated in the increasingly wealthy, formal, and (to their eyes) cold and nominal churches of the Big Denominations.

Methodists, Presbyterians, Congregationalists, and many others yearned for the kind of direct, joyous communion with God and fellow believers that they had found in the old-time, warm-hearted frontier religion of the Methodist preacher Peter Cartwright or the updated but still emotionally powerful revivalism of the Congregationalist evangelist Charles Finney.

Adrift in church environments that seemed to them not much more “Christian” than their worldly work-places, these believers struggled—in camp meetings, parlor meetings, and prayer closets—to retain an intimate, powerful connection with Christ. They sought to regain the “first love” of their conversions.

The teachings of Palmer, Finney, and the many other Wesleyan and Reformed holiness teachers of their century focused on this struggle. Some did and some did not stress the possibility of an instantaneous, complete post-conversion change from sinner to saint. But all helped build up the warm communal bond of those who were “going on in Jesus” and tasting a “deeper life” in him.

Many also taught that Christ wanted his children (including laypeople!) to reach out to the poor and outcast around them with material and spiritual help. And some saw in their experience of sanctification the foreshadowing of a new age of unity between Christians of all denominations.

Such were the visionaries and rank-and-filers of the holiness movement. Join us as we get to know them better.

Copyright © 2004 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History & Biography magazine. Click here for reprint information on Christian History & Biography.