Thousands of red brick homes, the shade of dried blood, enfold mountainous Medellín like the memory of an infamous killing. Death, Colombians say, is pan diario (daily bread), as commonplace as that staple of life. This culture of death yields 3,000 homicides a year in Medellín alone, by knife, machete, pistol, machine gun, grenade, and bomb.

Where Medellín's mountains touch the valley floor stands Bellavista. This prison complex, constructed of that same blood-red brick (painted blue and white) is where hundreds of Colombia's worst criminals and guerrillas have met an evil end in vendetta slayings. Fourteen years ago, violence reigned over Bellavista. But through the persistent efforts of Christians, Bellavista has become a spiritual clearinghouse where Colombians, deeply divided along religious, economic, and political lines, may reconcile their differences.

In Bellavista's chapel, white voile curtains cover the barred windows that overlook the prison's courtyards, where inmates once slaughtered both guards and other prisoners. Each Thursday, inmate small-group leaders from each of Bellavista's cellblocks fast, pray, and study Scripture. On this particular summer morning, a clutch of eight gathers in the chapel's corner office for worship, singing along with a videotape:

Sana nuestra tierra

("Heal our land")

Escucha hoy mi oración

("Hear my prayer today")

A tí levanto mi clamor

("To you I lift my cry")

Eyes closed, hands clasped or arms raised, the inmates lift their prayers for the salvation of Colombia. An hour later, the men prostrate themselves on the floor alongside an open Bible in the center of the room. As they weep and wail, the penetrating sound of their sobbing carries through the closed door into an adjoining room. "We repent. We exalt your name. Heal our land."

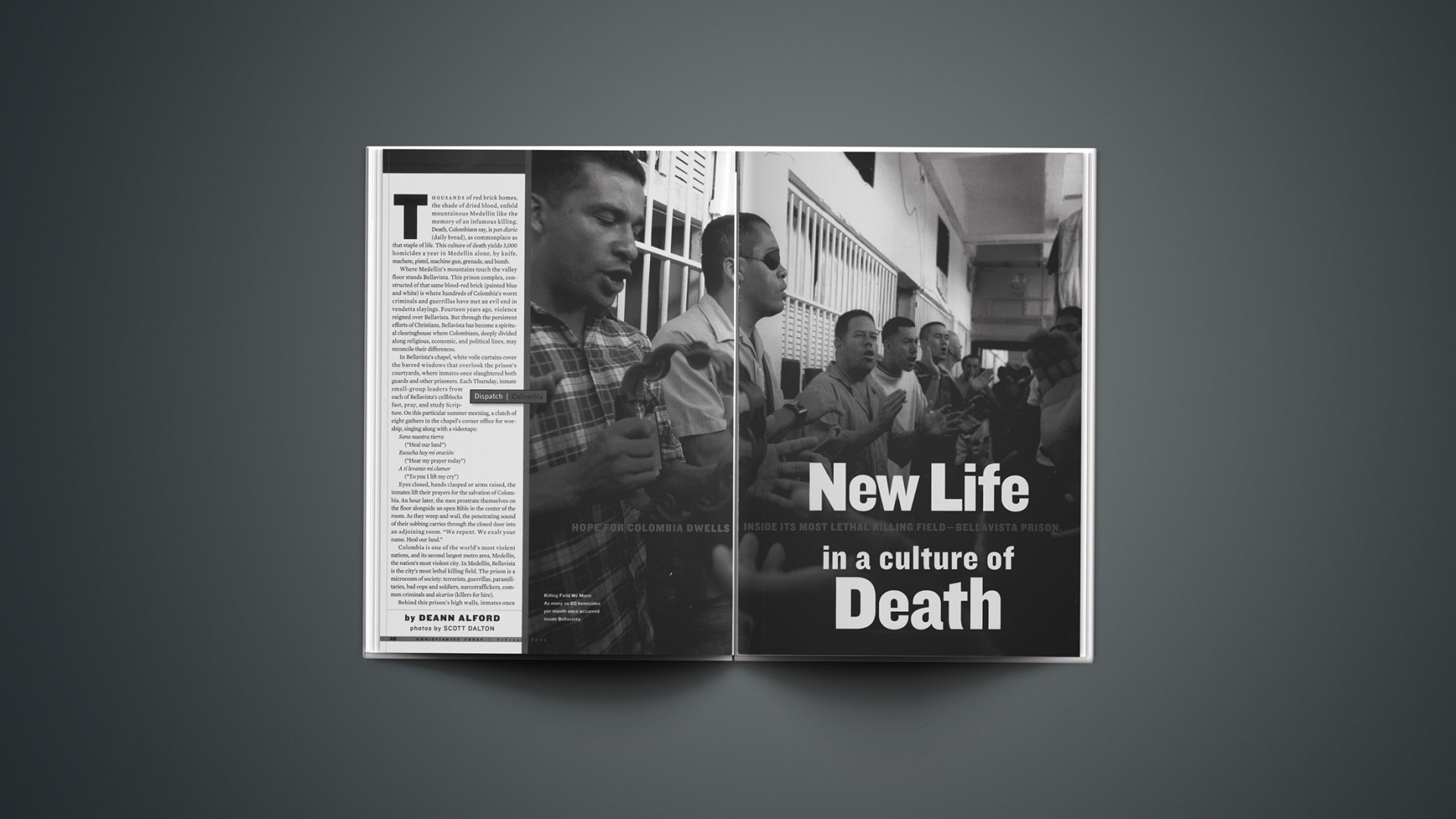

Colombia is one of the world's most violent nations, and its second largest metro area, Medellín, the nation's most violent city. In Medellín, Bellavista is the city's most lethal killing field. The prison is a microcosm of society: terrorists, guerrillas, paramilitaries, bad cops and soldiers, narcotraffickers, common criminals and sicarios (killers for hire).

Behind this prison's high walls, inmates once played soccer with a severed human head. Bella-vista's death toll ran as high as 60 a month as rival groups extended their warfare into the prison's maze of cardboard and scrap-wood cubicles, where inmates are quartered.

In January 1990, inmates rioted after daily violence prompted prison guards to walk off the job. Local leaders called on the Colombian army to intervene. But days into the standoff, Oscar Osorio, a Bellavista convict who became prison chaplain, gathered a handful of Christian volunteers associated with Chuck Colson's Prison Fellowship International. Singing hymns and carrying white flags, Osorio and his volunteers marched in procession through the prison gates, unsure if their lives would be spared.

Osorio found the prison's public address system was still working, so the chaplain boldly called prisoners to repentance. Stunning prison authorities, the inmates laid down their weapons. The riot was over. But more than that, the killing stopped and the gospel swept through Bellavista like holy fire. During the intervening 14 years, evangelicals have embraced Bellavista as an important place to help Colombians practice mutual forgiveness and achieve reconciliation.

'Lord of Bellavista'

"The presence of God is in that prison," says Jeannine Brabon, who heads Prison Fellowship for the Medellín region's 2 million people. Though less than 10 percent of inmates are believers, it's enough salt and light to bring peace.

That means, for example, Bellavista's police soccer team plays the delinquents' team, and right-wing paramilitaries play FARC (the Revolutionary Armed Forces, Colombia's most notorious guerrilla group). Before the 1990 revival, such games would have ended in a bloodbath.

"There can be hope for Colombia," Brabon says. Armies, weapons, and government legislation will never break the power of evil, she says. "You can't look to government and expect it to do what only God can do."

A child of missionary parents from Ohio and Michigan, Brabon was born in Colombia, where Protestants faced generations of severe discrimination until 1991, when government reforms ended the Catholic Church's privileged position. Her parents helped create Medellín's Biblical Seminary of Colombia. Brabon grew up during La ViolenciaS, the modern era of bloodshed triggered in 1948 when guerrillas assassinated presidential candidate Jorge Gaitán. Leaders of the FARC and other armed rebel groups trace their roots to guerrilla armies formed in the 1940s to press for political reforms. More than 200,000 died in the free-for-all before it segued in the late 1950s into the modern era of guerrillas warring to bring communism to Colombia's 44 million people.

By 1991, Brabon, an Old Testament scholar by training, had returned to Colombia from mission work in Spain to teach at the seminary. Chaplain Osorio asked her to preach at a Bellavista worship service. At the end of Brabon's sermon, 23 terrorists and sicarios accepted Christ, an event chronicled in journalist David Miller's book The Lord of Bellavista.

Brabon began discipling these killer-converts and holding Bible studies inside Bellavista. The next year, she took a giant step by launching one of the very few theological institutions inside a prison. Today, that institute is central to the strength of Bellavista's outreach. The training is deeper than what most Colombian pastors receive. Bellavista's brethren test doctrines and they know their Bibles.

Inmate encounters with the gospel start with the Psalm 27:10 mural near the prison entrance. Prisoners awake to the sounds of singing in the cellblocks. Believers hold evangelistic services. Each Christian aims to share his faith twice a day. On weekends the believers stage evangelism campaigns for their unbelieving fellow inmates and thousands of visitors.

"People tend to look down on people in prison," Brabon says. "They don't think they're people of worth. But they are. At the Cross there's level ground." And those prisoners want to reach Colombia for Christ, starting with the nation's 57,000 inmates. Prison has become a strong ministry focus for Colombia's evangelical Protestants, who are growing at about 7 percent a year. (According to a leading evangelical researcher in Colombia, there are 5 million Colombian evangelicals. In 1933, there were 15,000.)

A Rifle as God

How the Bellavista prison became a hub of Christian ministry draws in the stories of many individuals scarred by violence or abuse. Christianity Today gained rare access to Bellavista to interview several of the most influential individuals in ministry there.

In 1993, the army captured guerrilla Fredy Arias (then 21) and hauled him to a village jail deep in the heart of Colombia's war-torn Antioquia region.

Arias was a poster child for Colombia's social problems. His deep, abiding anger traced to an abusive stepfather, grinding family poverty, and a cousin who raped him repeatedly over two years. He became a street kid in Apartadó, a violent town near Colombia's border with Panama, dominated by narcotraffickers and four illegal armed groups. FARC guerrillas befriended Arias when he was 9 and taught him reading, writing, and Marxism. When he reached 17, they handed him a machine gun. The armed rebellion proved a natural outlet for his unfocused rage.

Colombia's rebel ranks are filled with teenage boys who become fighters because the armed factions offer pay, power, and purpose. For four years, Arias guarded hostages and fought against Colombia's army. He loved the rebels' cause: a new and just Communist society. "My rifle was my only god because it saved my life," Arias says.

After his capture, Arias arrived at Bellavista poised to continue his bloodletting. But his thoughts turned to a little girl who watched as Arias helped murder her father for spying. His soul was pricked by a contradiction. "If supposedly we were social transformers, why did we kill?" Arias says. "The Bible began to speak to me. What kind of transformer was I if I was destroying what God created? I began to cry." One night after somebody talked with him about Christ, Arias got on his knees in bed to beg God's forgiveness.

One inmate who served time with Arias watched God change a coarse, strong-willed rebel to a man utterly committed to Jesus. "Fredy had a lot of problems, and God took his hand and wouldn't let go," he says.

Freed in late 1994, Arias moved into a halfway house sponsored by Prison Fellowship. Like many of Colombia's warriors, his only professional skill was efficient, remorseless murder. Brabon taught him to paint houses, and that trade helps him earn a living.

In 2001 Arias wrote an open letter to the families of missing New Tribes missionaries Dave Mankins, Rick Tenenoff, and Mark Rich, kidnapped by FARC in 1993 and later declared dead. Arias shared the story of his conversion and asked forgiveness for rebel involvement. Now 31, Arias aspires to attend seminary to equip himself for helping street kids.

Arias recently enrolled in school as a step forward to his ministry goal. Where once he read Karl Marx, Arias studies the Bible and preaches in the Bellavista cellblocks. It's his way of offering back more than what he took from his homeland.

"Every day I ask myself why my country is like it is," Arias says. "It's for lack of God."

Blinded and Blessed

According to estimates, 30,000 Colombians are members of paramilitary and rebel groups. Very few of them ever face prosecution for their crimes, and Colombians by the millions have been their victims during the last 50 years.

Alex Puerta had every reason to embrace Colombia's ruthless ethic of murderous reprisal. A rebel sympathizer killed his father, and guerrillas forced his family from their home, stole their horses and cattle, and confiscated most of his family's plantain farm in Apartadó. But Puerta says he surrendered "life, soul, and hat" to Christ because of rebel death threats against him. He turned down the paramilitaries' invitation to take revenge.

Then an armed neighbor threatened Puerta and physically assaulted his mother. Though enraged and tempted to grab a rifle, Puerta suddenly stopped himself. "I saw I could become a vengeful person, or I could follow God," he says. "I realized that if I didn't forgive them, I wasn't really a Christian."

His pledge endured a trial by fire in the predawn hours of September 20, 1995. Puerta, then 27, was riding in a bus filled with 27 farm workers. FARC guerrillas stopped the bus. Four boarded with machine guns and forced everyone off, marching the group to a spot where 60 guerrillas were waiting.

Puerta immediately prayed. Sensing that death was at hand, he started to sing the chorus "You are my hiding place." Rebels tied the workers' hands with plantain rope and made them lie face down. "I told my people to remember the Word of God I had shared with them and get ready to enter God's presence," he recalls.

As the guerrillas began the slaughter, Puerta realized that while most of his workers had heard the gospel, the guerrillas had not. Seconds later, a bullet lodged in the bridge of his nose, grazing the optic nerve of his left eye. The bullet's impact blew out his right eye socket and part of his face.

Puerta went blind, but, he recalls, "I began to shout with all my heart, 'Christ loves you!' " A guerrilla's kick shattered his jaw, silencing him. Other guerrillas killed the remaining workers with guns and machetes. Drowning in his own blood but clinging to life, Puerta was the massacre's only survivor.

After five reconstructive surgeries, Puerta has a new face. He refers to the massacre as "the accident."

"If you're close to God, the worst thing can happen to you, and it won't hurt you," he says. "I don't ever want to feel like a victim. God is my healer."

When word got out that Puerta was alive, rebels began hunting him down. Christians hid Puerta for two years. Then, cautiously, he began to share his testimony at Bellavista. An inmate who took part in the massacre heard that testimony and feared Puerta would turn him in. But Puerta sent word to the inmate that he had forgiven him. Later, two other inmates heard Puerta's story and broke down sobbing. Both were top guerrilla leaders inside Bellavista. Puerta's story led one of them to Christ. That leader declared Puerta a man of valor. The death order was rescinded, allowing Puerta to minister openly.

Puerta still carries his military photo id; it portrays a strikingly handsome 18-year-old, serious but not angry. Now, a black patch covers his eye socket. His smile pulls to one side as half his face remains numb. An x-ray revealed that many pieces of shrapnel were lodged in his skull. The bullet destroyed his sense of smell. His neck bears long, white machete scars. Brabon says Puerta is reconciliation and forgiveness incarnate. "He is the message for Colombia."

Puerta graduated from seminary in 2003, serving his year-long ministry practicum at Bellavista, where he taught Bible and discipled prisoners. Before "the accident," Puerta struggled with why God allows suffering. "There was a profound silence until I understood that the most important thing in life is to love him," Puerta says. "He is my life. God allows problems but gives us victory over them if we trust in him.

"God is good. No matter the circumstance, he is all that matters."

Hope on the Line

"Prison ministry" usually means those on the outside reaching in, but not at Bellavista. An inmate-produced radio program, Cry of Hope, broadcasts from behind the prison's walls. It's a shining example of the inmates' highest aspiration: to reach their nation.

Before a recent 10:30 A.M. broadcast, chapel worship leader Daniel Muriel calls a Christian radio station from a prison telephone near the chapel's pulpit. Muriel, pencil behind his ear, clutches the receiver and greets listeners: "Jesus Christ is our rock and salvation, and we're safe every day with him. He is our king and hope and strength." He quotes part of Psalm 27 from memory, then says, "He will take care of you. God loves you so much. We want God to bless your life. We want to encourage you. Set your eyes on Jesus Christ."

He passes the phone to an assistant who holds it high as Muriel plays at the keyboard. Prisoners gather around the phone, singing and clapping, "The Lord is the light and the rock of my salvation" in soulful, exuberant worship. The chapel steward waves for quiet and passes the phone to preacher Enrique Rivera, whose text is Deuteronomy 1. Rivera paces behind the pulpit, gesturing broadly with the hand not clutching the receiver: "He who has ears to hear, let him hear. Let the Word change the way you live." The program ends after 30 minutes, right on schedule.

Rivera hangs up the phone as if he'd been chatting with a friend. It's hard to imagine the strict but affable Rivera, 36, before he turned to Christ eight years ago. He was a policeman who did "social cleansing"—killing off bad elements in Medellín. Three murder convictions landed him in Bellavista. But his life was turned upside down by what he found in a stolen briefcase: a New Testament. In jail and handcuffed to fellow prisoners, Rivera pored over his stolen Bible. On his first day in Bellavista, he heard the gospel and accepted Christ.

Brabon attributes the success of Bellavista and its daughter churches in prisons across Colombia to the willingness of believers to sever ties with their poisonous past. "There's no power without purity, and they're willing to pay a price for God to work," she says.

Accountability doesn't stop with conversion. A Bellavista ministry leader who sins grievously must step down from his post for at least six months until he is restored through counseling and peer ministry. Brabon says, "They're in a pressure cooker, but they realize they're not going to be any different coming out if they're not different inside the prison."

One critical step for Bellavista's Christian inmates is a commitment to reach out regardless of their circumstances. If a believer's sentence is long, he becomes a career missionary of sorts to Colombia's prison system. If an inmate is released, often he returns to his former peer group (sicarios, guerrillas, narcotraffickers, or common criminals) to reach them for Christ.

Medellín itself is full of men who have served time at Bellavista and now work in rehabilitation programs, drug ministries, and churches. For Bellavista believers, commitment to the Cross doesn't come cheap. They're willing to pay the price for obedience, even unto death. At least one believer was martyred for his faith in the mid-1990s. "We're under [spiritual] attack all the time, in every way," Brabon says, asking for prayer for Bellavista's inmate ministers. "When we're in print, we come under horrific attack."

The deep hope of Bellavista's evangelist-convicts is that their prison revival will chart a path for one-to-one reconciliation, moving their nation toward peace. "Humanly speaking, there's no solution" to Colombia's quagmire, says Richard Luna, director of Open Doors Latin America.

Rivera says, "The only thing that can change this is a miracle of God."

Given that violent crime flourishes almost completely unpunished in Colombia, it's a miracle that any of Bellavista's brethren are alive and that they survive in prison. "When the people of Israel were in the desert, they experienced the glory of God," says Prison Fellowship volunteer Omar Monsalve. "Why did I land in jail? We're all here by the grace of God."

Deann Alford is a writer and editor in Austin, Texas.

Copyright © 2004 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

Also posted today is the testimony of a converted felon.

The Prison Fellowship International web site has more information.

More CT articles from Colombia include:

Kidnappers Release Two Christian Relief Volunteers in Colombia | Ransom demand paid for evangelical lawyer and businessman. (Jan. 05, 2004)

Colombian Rebels Kill Evangelical Pastors | Two church leaders ambushed in August. (Sept. 03, 2002)

Rebels Force Churches to Close in Colombia | Christians accused of political involvement in May 26 elections (May 16, 2002)

Missionaries Defy Terrorist Threat in Colombia | U.S. Embassy says North Americans are guerrilla targets. (April 30, 2002)

Missionaries May Be Target Of FARC Guerrillas | U.S. embassy in Colombia issues warning to missionaries and churches. (March 08, 2002)

New Tribes Missionaries Kidnapped in 1993 Declared Dead | Mission concludes Colombian guerrillas shot the three men in 1996. (Sept. 27, 2001)

Risking Life for Peace | Caught between rebels, paramilitaries, and crop-dusters, peacemaking Christians put their lives on the line in violent Colombia. (Sept. 07, 2001)

Hostage Pastor Released Unharmed In Colombia | Wife pledges to stay in Colombia because the kidnappers cannot stop the Lord's work. (Aug. 20, 2001)

CT articles on prison ministry include:

The Legacy of Prisoner 23226 | Twenty-six years after leaving prison, Charles Colson has become one of America's most significant social reformers. (July 29, 2001)

Prison Ministry in Mozambique | Missionary says women suffer grave injustices. (Aug. 4, 2000)

Setting Captives Free | It takes more than getting a woman inmate out of jail to turn her life around (Jan. 10, 2000)