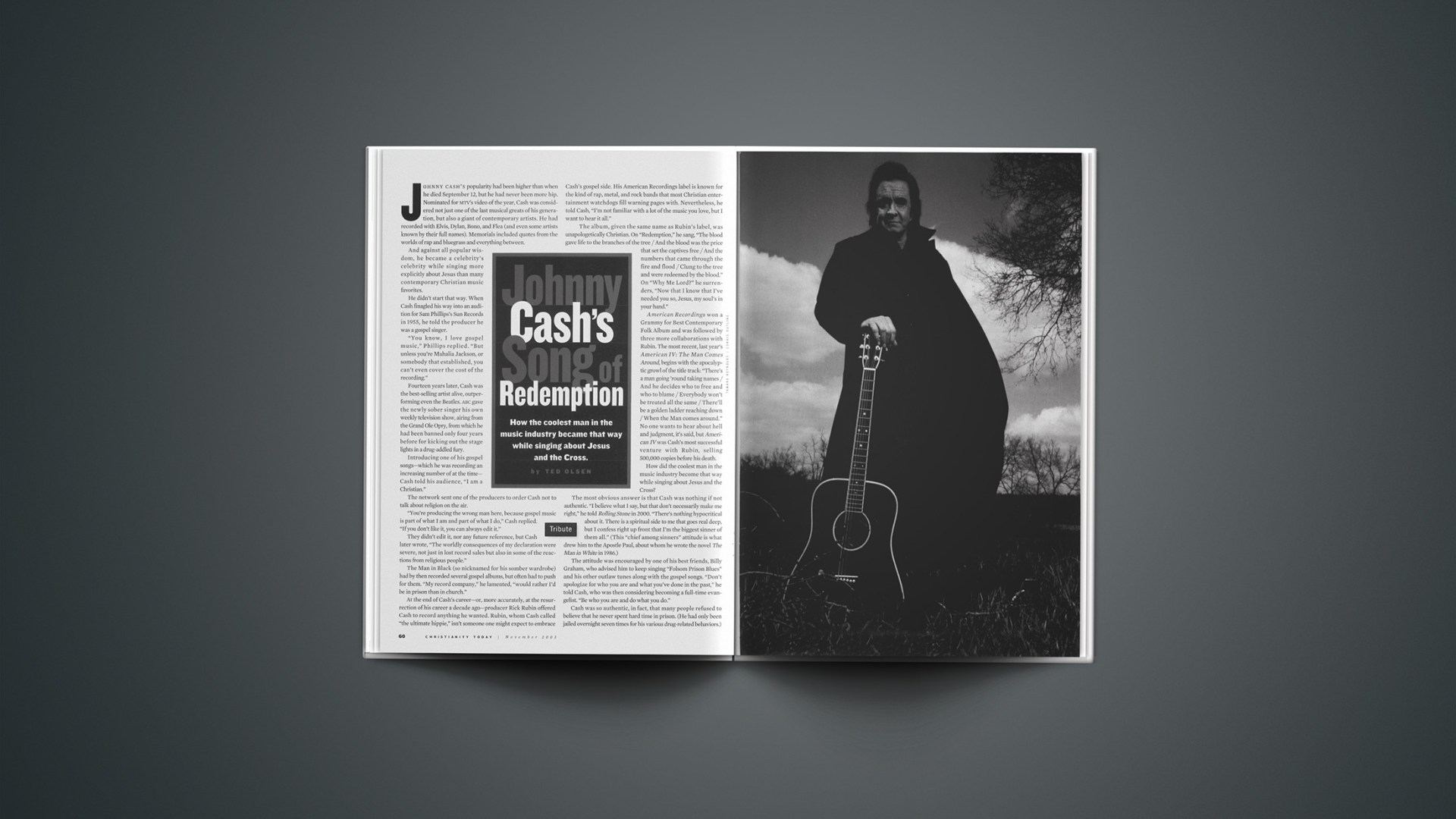

JOHNNY CASH’S popularity had been higher than when he died September 12, but he had never been more hip. Nominated for MTV’s video of the year, Cash was considered not just one of the last musical greats of his generation, but also a giant of contemporary artists. He had recorded with Elvis, Dylan, Bono, and Flea (and even some artists known by their full names). Memorials included quotes from the worlds of rap and bluegrass and everything between.

And against all popular wisdom, he became a celebrity’s celebrity while singing more explicitly about Jesus than many contemporary Christian music favorites.

He didn’t start that way. When Cash finagled his way into an audition for Sam Phillips’s Sun Records in 1955, he told the producer he was a gospel singer.

“You know, I love gospel music,” Phillips replied. “But unless you’re Mahalia Jackson, or somebody that established, you can’t even cover the cost of the recording.”

Fourteen years later, Cash was the best-selling artist alive, outperforming even the Beatles. ABC gave the newly sober singer his own weekly television show, airing from the Grand Ole Opry, from which he had been banned only four years before for kicking out the stage lights in a drug-addled fury.

Introducing one of his gospel songs—which he was recording an increasing number of at the time—Cash told his audience, “I am a Christian.”

The network sent one of the producers to order Cash not to talk about religion on the air.

“You’re producing the wrong man here, because gospel music is part of what I am and part of what I do,” Cash replied. “If you don’t like it, you can always edit it.”

They didn’t edit it, nor any future reference, but Cash later wrote, “The worldly consequences of my declaration were severe, not just in lost record sales but also in some of the reactions from religious people.”

The Man in Black (so nicknamed for his somber wardrobe) had by then recorded several gospel albums, but often had to push for them. “My record company,” he lamented, “would rather I’d be in prison than in church.”

At the end of Cash’s career—or, more accurately, at the resurrection of his career a decade ago—producer Rick Rubin offered Cash to record anything he wanted. Rubin, whom Cash called “the ultimate hippie,” isn’t someone one might expect to embrace Cash’s gospel side. His American Recordings label is known for the kind of rap, metal, and rock bands that most Christian entertainment watchdogs fill warning pages with. Nevertheless, he told Cash, “I’m not familiar with a lot of the music you love, but I want to hear it all.”

The album, given the same name as Rubin’s label, was unapologetically Christian. On “Redemption,” he sang, “The blood gave life to the branches of the tree / And the blood was the price that set the captives free / And the numbers that came through the fire and flood / Clung to the tree and were redeemed by the blood.” On “Why Me Lord?” he surrenders, “Now that I know that I’ve needed you so, Jesus, my soul’s in your hand.”

American Recordings won a Grammy for Best Contemporary Folk Album and was followed by three more collaborations with Rubin. The most recent, last year’s American IV: The Man Comes Around, begins with the apocalyptic growl of the title track: “There’s a man going ’round taking names / And he decides who to free and who to blame / Everybody won’t be treated all the same / There’ll be a golden ladder reaching down / When the Man comes around.” No one wants to hear about hell and judgment, it’s said, but American IV was Cash’s most successful venture with Rubin, selling 500,000 copies before his death.

How did the coolest man in the music industry become that way while singing about Jesus and the Cross?

The most obvious answer is that Cash was nothing if not authentic. “I believe what I say, but that don’t necessarily make me right,” he told Rolling Stone in 2000. “There’s nothing hypocritical about it. There is a spiritual side to me that goes real deep, but I confess right up front that I’m the biggest sinner of them all.” (This “chief among sinners” attitude is what drew him to the Apostle Paul, about whom he wrote the novel The Man in White in 1986.)

The attitude was encouraged by one of his best friends, Billy Graham, who advised him to keep singing “Folsom Prison Blues” and his other outlaw tunes along with the gospel songs. “Don’t apologize for who you are and what you’ve done in the past,” he told Cash, who was then considering becoming a full-time evangelist. “Be who you are and do what you do.”

Cash was so authentic, in fact, that many people refused to believe that he never spent hard time in prison. (He had only been jailed overnight seven times for his various drug-related behaviors.)

But Cash’s resilient repute was about more than authenticity. Many musicians are authentic, including authentic thugs, authentic boors, authentic sex addicts, or authentic frauds. Cash’s true strength was authenticity’s elder brother, integrity.

Cash had integrity in the moral sense, certainly. Once sober, he made up concerts that he’d skipped or fudged during his amphetamine binges, for example. But Cash had integrity in the sense of being a whole. In his liner notes for American Recordings, Cash lists 32 subjects he loves in songs, from railroads and whiskey to Mother and larceny. But in all these songs he was really singing about one thing: the connection between sin and redemption. He saw that on either side of sin was enjoyment and death, and that on either side of redemption was Death and Enjoyment.

Cash never denied the pleasure of sin, and many songs reflect that pleasure honestly—but unlike those in other outlaw tunes, the subjects of Cash’s songs rarely sin without consequences. “I shot a man in Reno just to watch him die,” regretfully sings the blue man in Folsom Prison. “I took a shot of cocaine and I shot my woman down,” sings the prisoner of “Cocaine Blues.”

Even Cash’s love songs carry the theme: In “I Walk the Line,” he worries about his own infidelity. In “Jackson,” he tries to cover it up. “Ring of Fire,” written by June Carter Cash and sung by Johnny while the two were flirting but married to others, carries unsubtle references to damnation.

But for Cash, the worst consequence of sin wasn’t what happened to the sinner. Nowhere is this clearer than in the final moments of the MTV award-nominated “Hurt” video, where the lyrics “I will let you down / I will make you hurt” are illustrated with Christ’s crucifixion.

In a 2000 interview with Rolling Stone, Cash compared drugs’ spiritual consequences with their physical and emotional devastation: “To put myself in such a low state that I couldn’t communicate with God, there’s no lonelier place to be. I was separated from God, and I wasn’t even trying to call on him. I knew that there was no line of communication.”

Though he’d professed Christ at age 12, Cash wrote that by 1967, “there was nothing left of me… I had drifted so far away from God and every stabilizing force in my life that I felt there was no hope.” He decided to crawl into Nickajack Cave on the Tennessee River, get lost, and die. “The absolute lack of light was appropriate,” he wrote. “My separation from Him, the deepest and most ravaging of the various kinds of loneliness I’d felt over the years, seemed finally complete.

“It wasn’t. I thought I’d left Him, but He hadn’t left me. I felt something very powerful start to happen to me, a sensation of utter peace, clarity, and sobriety…Then my mind started focusing on God. He didn’t speak to me—He never has, and I’ll be surprised if He ever does—but … I became conscious of a very clear, simple idea: I was not in charge of my own destiny. I was not in charge of my own death.”

He found his way out of the cave, determined to get clean and sober. He made a good start, and he’s been honest about the slips and relapses along the way—and not just with drugs. “They just kind of hold their distance,” he told Rolling Stone. “I could invite them in: the sex demon, the drug demon. But I don’t. They’re very sinister. You got to watch ’em. They’ll sneak up on you. All of a sudden there’ll be a beautiful little Percodan laying there, and you’ll want it.”

The connection with God makes it all worth it, he said: “The greatest joy of my life was that I no longer felt separated from Him. Now he is my Counselor, my Rock of Ages to stand upon.”

Cash, many obituaries suggested, seemed obsessed with death. It was something he denied. “I am not obsessed with death; I’m obsessed with living,” he said in 1994. “The battle against the dark one and the clinging to the right one is what my life is about.”

Living, he knew, was death to self. His favorite verse, he often said, was Romans 8:13: “For if you live according to the sinful nature, you will die; but if by the Spirit you put to death the misdeeds of the body, you will live.”

A paradox? Not to Cash, who encountered death shortly before accepting an altar call. His brother Jack, two years his senior, fell on a table saw, cut from ribs to groin. “Mama, don’t cry over me,” he said, as Johnny and the rest of the family stood by. “I was going down a river, and there was a fire on one side and heaven on the other. I was crying, ‘God, I’m supposed to go to heaven. Don’t you remember? Don’t take me to the fire.’ All of a sudden, I turned, and now, mama, can you hear the angels singing?”

She said that she couldn’t, and Jack squeezed her hand.

“Oh, mama, I wish you could hear the angels singing,” he said, and died.

Like Christ, Cash felt no shame or theological dissonance at crying in the face of death. But make no mistake: he never forgot the joy waiting on the other side. Now, on the other side of the river, the Man in Black wears glorious white, reunited with his brother and face-to-face with his Lord.

Later this year, it has been reported, American Recordings will release a CD boxed set, with as many as 100 outtakes of Cash’s work with Rubin over the last decade. Among the CDs will be Redemption Songs and the long-delayed Songs from My Mother’s Hymn Book. Surely in the other albums there will be tunes of death and sin. Taken as a whole, it will be unmistakable that Cash was correct from his first day at Sun Records: He really was a singer of the gospel.

Ted Olsen is online managing editor for

Christianity Today

.Copyright © 2003 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere

Cash’s official site, JohnnyCash.com, offers photos, music clips, a discography, a forum board, and many other items.

American Recordings’ official Johnny Cash site, JohnnyCashMusic.com, is good for news and links, including reams of obituaries.

CMT has a tribute video.

Cash’s “Hurt” video is available in both RealVideo and Windows Media (high bandwidth | low bandwidth) formats.

Steve Beard, who wrote about Cash’s Christianity for the book Spiritual Journeys, also compiled several obituaries and tributes.

Rolling Stone has published some excellent articles on Cash over the years.