In July 1974, 2,700 evangelical Protestants from 150 nations gathered in Lausanne, Switzerland, for the first International Congress on World Evangelization. Time magazine called the gathering “possibly the widest ranging meeting of Christians ever held.” The congress produced the Lausanne Covenant, which set evangelization into a broader context than had been the practice among evangelicals to that point—including the purposes of God, the authority of Scripture, the uniqueness of Christ, the mission of the church, the power of the Holy Spirit and the second coming of Christ. It has been hailed as one of the most significant documents of the 20th century.

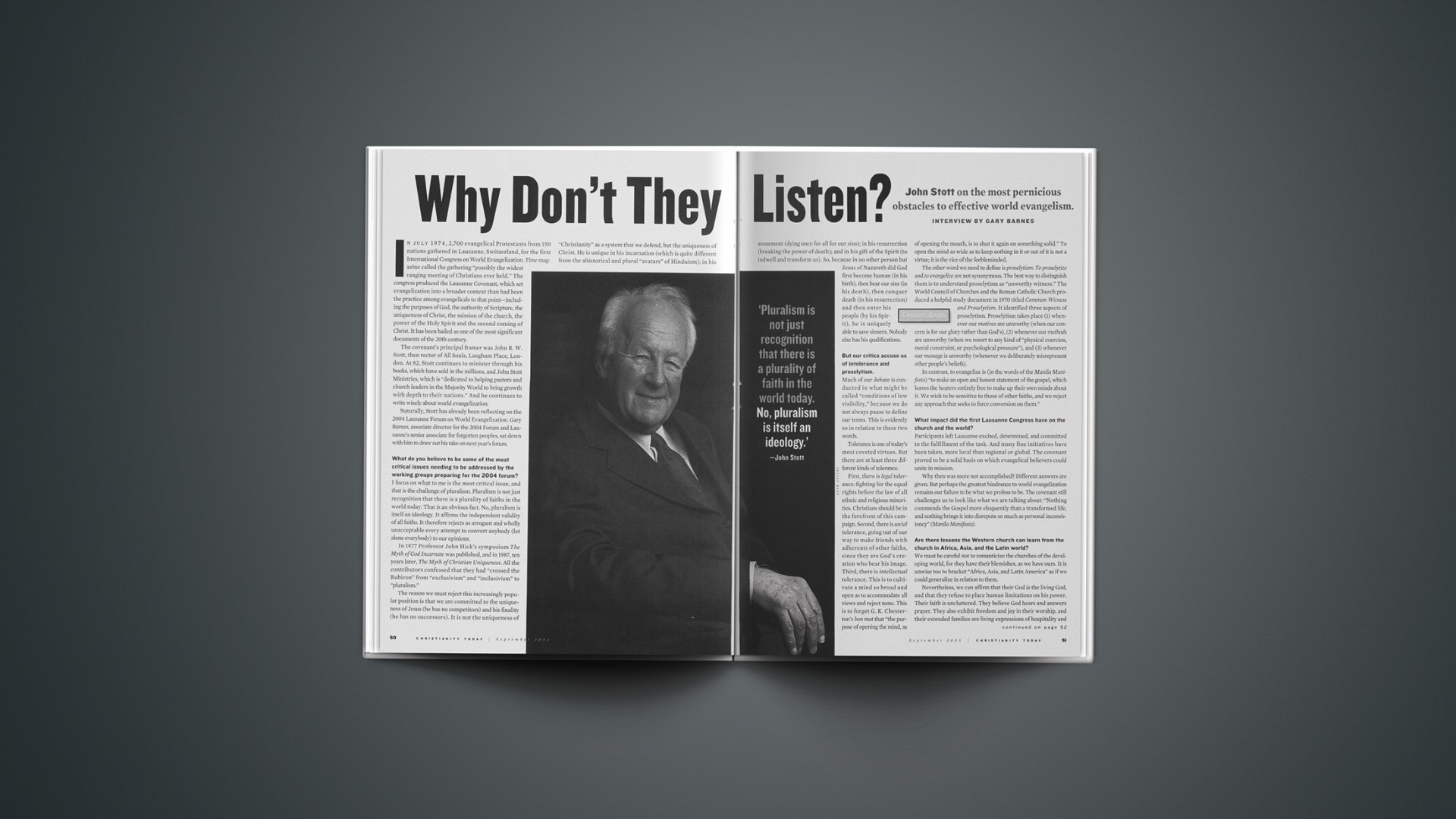

The covenant’s principal framer was John R. W. Stott, then rector of All Souls, Langham Place, London. At 82, Stott continues to minister through his books, which have sold in the millions, and John Stott Ministries, which is “dedicated to helping pastors and church leaders in the Majority World to bring growth with depth to their nations.” And he continues to write wisely about world evangelization.

Naturally, Stott has already been reflecting on the 2004 Lausanne Forum on World Evangelization. Gary Barnes, associate director for the 2004 Forum and Lausanne’s senior associate for forgotten peoples, sat down with him to draw out his take on next year’s forum.

What do you believe to be some of the most critical issues needing to be addressed by the working groups preparing for the 2004 forum?

I focus on what to me is the most critical issue, and that is the challenge of pluralism. Pluralism is not just recognition that there is a plurality of faiths in the world today. That is an obvious fact. No, pluralism is itself an ideology. It affirms the independent validity of all faiths. It therefore rejects as arrogant and wholly unacceptable every attempt to convert anybody (let alone everybody) to our opinions.

In 1977 Professor John Hick’s symposium The Myth of God Incarnate was published, and in 1987, ten years later, The Myth of Christian Uniqueness. All the contributors confessed that they had “crossed the Rubicon” from “exclusivism” and “inclusivism” to “pluralism.”

The reason we must reject this increasingly popular position is that we are committed to the uniqueness of Jesus (he has no competitors) and his finality (he has no successors). It is not the uniqueness of “Christianity” as a system that we defend, but the uniqueness of Christ. He is unique in his incarnation (which is quite different from the ahistorical and plural “avatars” of Hinduism); in his atonement (dying once for all for our sins); in his resurrection (breaking the power of death); and in his gift of the Spirit (to indwell and transform us). So, because in no other person but Jesus of Nazareth did God first become human (in his birth), then bear our sins (in his death), then conquer death (in his resurrection) and then enter his people (by his Spirit), he is uniquely able to save sinners. Nobody else has his qualifications.

But our critics accuse us of intolerance and proselytism.

Much of our debate is conducted in what might be called “conditions of low visibility,” because we do not always pause to define our terms. This is evidently so in relation to these two words.

Tolerance is one of today’s most coveted virtues. But there are at least three different kinds of tolerance.

First, there is legal tolerance: fighting for the equal rights before the law of all ethnic and religious minorities. Christians should be in the forefront of this campaign. Second, there is social tolerance, going out of our way to make friends with adherents of other faiths, since they are God’s creation who bear his image. Third, there is intellectual tolerance. This is to cultivate a mind so broad and open as to accommodate all views and reject none. This is to forget G. K. Chesterton’s bon mot that “the purpose of opening the mind, as of opening the mouth, is to shut it again on something solid.” To open the mind so wide as to keep nothing in it or out of it is not a virtue; it is the vice of the feebleminded.

The other word we need to define is proselytism. To proselytize and to evangelize are not synonymous. The best way to distinguish them is to understand proselytism as “unworthy witness.” The World Council of Churches and the Roman Catholic Church produced a helpful study document in 1970 titled Common Witness and Proselytism. It identified three aspects of proselytism. Proselytism takes place (1) whenever our motives are unworthy (when our concern is for our glory rather than God’s), (2) whenever our methods are unworthy (when we resort to any kind of “physical coercion, moral constraint, or psychological pressure”), and (3) whenever our message is unworthy (whenever we deliberately misrepresent other people’s beliefs).

In contrast, to evangelize is (in the words of the Manila Manifesto) “to make an open and honest statement of the gospel, which leaves the hearers entirely free to make up their own minds about it. We wish to be sensitive to those of other faiths, and we reject any approach that seeks to force conversion on them.”

What impact did the first Lausanne Congress have on the church and the world?

Participants left Lausanne excited, determined, and committed to the fulfillment of the task. And many fine initiatives have been taken, more local than regional or global. The covenant proved to be a solid basis on which evangelical believers could unite in mission.

Why then was more not accomplished? Different answers are given. But perhaps the greatest hindrance to world evangelization remains our failure to be what we profess to be. The covenant still challenges us to look like what we are talking about: “Nothing commends the Gospel more eloquently than a transformed life, and nothing brings it into disrepute so much as personal inconsistency” (Manila Manifesto).

Are there lessons the Western church can learn from the church in Africa, Asia, and the Latin world?

We must be careful not to romanticize the churches of the developing world, for they have their blemishes, as we have ours. It is unwise too to bracket “Africa, Asia, and Latin America” as if we could generalize in relation to them.

Nevertheless, we can affirm that their God is the living God, and that they refuse to place human limitations on his power. Their faith is uncluttered. They believe God hears and answers prayer. They also exhibit freedom and joy in their worship, and their extended families are living expressions of hospitality and care. They take naturally to evangelism, and new converts are expected immediately to witness to Christ their Savior. Spontaneity is the word which springs naturally to my mind to describe their Christian discipleship, and the most appropriate Greek word might be parresia which means outspokenness; it denotes a holy boldness and freedom in both worship and witness.

Do you have concerns about the church in the West?

My main concern for the church everywhere is that we often do not look like what we are talking about. We make great claims for Christ, but there is often a credibility gap between our words and our actions.

For example, consider the implications of 1 John 4:12: “No one has ever seen God; but if we love one another, God lives in us and his love is made complete in us.” The invisibility of God is a great problem. It was already a problem to God’s people in Old Testament days. Their pagan neighbors would taunt them, saying, “Where is now your God?” Their gods were visible and tangible, but Israel’s God was neither. Today in our scientific culture young people are taught not to believe in anything which is not open to empirical investigation.

How then has God solved the problem of his own invisibility? The first answer is of course “in Christ.” Jesus Christ is the visible image of the invisible God. John 1:18: “No one has ever seen God, but God the only Son has made him known.”

“That’s wonderful,” people say, “but it was 2,000 years ago. Is there no way by which the invisible God makes himself visible today?”

There is. We return to 1 John 4:12: “No one has ever seen God.” It is precisely the same introductory statement. But instead of continuing with reference to the Son of God, it continues: “If we love one another, God dwells in us.” In other words, the invisible God, who once made himself visible in Christ, now makes himself visible in Christians, if we love one another. It is a breathtaking claim. The local church cannot evangelize, proclaiming the gospel of love, if it is not itself a community of love.

Copyright © 2003 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere

The text of the Lausanne Covenant is available at the website of the Lausanne Committee for World Evangelization.

Previous CT articles on John Stott include:

Basic Stott | The wisdom of evangelicalism’s premier teacher on gender, charismatics, leaving the Church of England, the poor, evangelical fragmentation, Catholics, the future, and other subjects (Jan. 8, 1996)

Pottering and Prayer | As John Stott turns 80, he still finds weeds to pull, birds to watch, and petitions to make. (April 27, 2001)

The Quotable Stott | Reflections on the occasion of John R.W. Stott’s 80th birthday. (April 27, 2001)

An Elder Statesman’s Plea | John Stott’s ‘little statement on evangelical faith’ reveals the strengths and limitations of the movement he helped create. (Feb. 7, 2000)

Guardian of God’s Word | The amazingly balanced, wise, biblical, and global ministry of a local pastor, John Stott.” (September 16, 1996)

Articles on Stott from Christianity Today sister publication Books & Culture include:

WWJSD | The global ministry of John Stott. (March/April 2002)

Basic Christianity—with an Oxbridge Accent | John Stott and evangelical renewal. (Sept./Oct. 2000)