Visualizing the future, several businesspersons at a Manhattan hotel are acting out what the ideal corporate board meeting will look like in 2012. "May all the decisions we make today be guided by values and by love," the board chairman says. "Let's meditate on it. Tune in to your intuition on all levels."

It's the Spirit in Business World Conference, where more than 500 businesspeople and assorted "change agents" have come to help unleash each other's inner powers. They will spend three days spurring each other on to positive thoughts at the Sheraton New York Hotel and Towers, a sanctuary from the grit and litter outside. Then they will go to the ends of the earth as part of a fledgling movement to transform the world.

Yes, they're believers—in human potential. They believe in the power of enlightened business to imbue life with meaning. Many of them, especially their leaders, believe business will help usher in a universal shift in consciousness.

They mean many things by the term shift in consciousness, including the notion that businesspeople should rely less on rational thought and more on intuitive "inner wisdom." On a less esoteric level, the envisioned business revolution would affirm values—rather than shareholder value—as the driving force of business. Paradoxically, most of those values have biblical roots.

The spirit-minded consultants, executives, and academics are, after all, into ethics as much as energy fields. One of at least 15 such conferences taking place yearly (up from two in 1994), this event is sponsored by Greenfield, Massachusetts-Based Spirit in Business Inc. It is one of a cluster of conference organizers unifying the disciples and doctrines of a constellation of neopagan and panreligious philosophers, metaphysical futurists, and self-proclaimed gurus who recognize the power of business in today's society.

They grapple with what to call their movement, which is growing behind the wedge of spirituality in the workplace. Outsiders, such as Regent College professor of marketplace theology R. Paul Stevens, call it the New Business Spirituality. One of the institutional hubs of the movement, the Ojai, California-based World Business Academy, uses the term New Paradigm business. That term, after all, denotes a "paradigm shift" or change in fundamental assumptions about the nature of reality.

That is what the visionaries in the movement advocate: business playing a key role in a paradigm shift from scientific materialism to a metaphysical outlook—the mind influencing or dictating reality. Going global will help. The conference goal of launching a Spirit in Business World Institute & Global Network is meant to unify member institutes around the world and help corporate leaders to connect with a transforming divinity—the god within, or something.

Old Song, New Arrangement

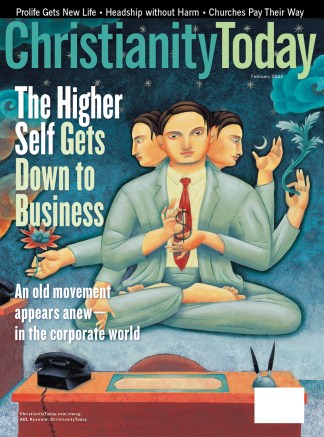

This may sound like that ol' time New Age religion, but only because it is. Having shed fringe elements like crystal gazing, the New Age movement's fundamental tenets—both human-centered spirituality and its oddly compatible neopagan cousins—are moving into the mainstream.

In this movement, infiltrating the daily world of business is paramount. The New Age movement of the 1980s discovered the business world in the 1990s. New Age bookstores planted business sections, and the business sections of mainstream booksellers began sprouting New Age-tinted titles by authors from pop guru Deepak Chopra (The Seven Spiritual Laws of Success) to Michael Ray (The New Paradigm in Business), a professor at Stanford University's graduate business school.

BusinessWeek counted 79 books on spirituality in the workplace in its November 1999 cover story. A search on "business spirituality" at Amazon.com now produces 116 titles. Not all have New Paradigm content and some reflect Christian approaches, but the New Age faction has definitely taken its place in the emerging business and workplace spirituality.

"There is a feeling we know as spirit—only the names and words change," Terry Mollner, a top New Paradigm consultant and author, tells 150 people at a Founders Meeting for the global institute and network. "Imagine your nervous systems connecting, and we're all part of the one. … a circle of intentionality and knowing and warmth."

Before the session ends they will pass around a black stone. Upon receiving it, each is to say "the word that gives force to what you will bring to the conference." Imagination. Authenticity. Mystery. There is little repetition, except for a few words like Joy. The stone continues around the room. Magic. Intuition. Connection. Divinity. Eternal life.

A bell chimes, and Mollner shuts his eyes to give a closing blessing. "Let the pure light of intentionality behind each of these words resonate," he says. "We are all in this together. We are all in this together. We're here to be open-minded. We're going to rise from here with an energy that says, 'We're going to serve as servant leaders—just for the d— joy of it.' Amen."

Wha. … ?

In the new millennium, the New Age label itself falls away. Like Baptist and other churches disowning their denominational identifiers to present themselves as "community churches," postmodern New Agers would rather not be encumbered by the pigeonholing of the New Age brand name.

The code words for New Age spirituality remain—intuition, transformation, interconnectedness—but even New Age Journal changed its name to Body & Soul last year to break free of extremist or negative connotations. The preferred term within the movement, emerging mainstream, is telling.

Into the mainstream, indeed, basic New Age tenets are flowing through the culvert of business. As Mollner indicated, everyone is interconnected and, by extension, one with that undefined deity of different names. Monism—like much New Age thought, borrowed from Eastern religions—holds that everything and everyone, including the divine, is one. Hence the New Age tendency to blur the distinction between the human and the divine.

This religious belief sneaks into the office through the secular guise of seemingly neutral meditation techniques (See "Prosperity Consciousness," p. 38). The Spirit in Business conference offered no fewer than nine talks on or exercises in inner-directed meditation. Not to mention the homily that S.N. Goenka, founder of the Vipassana Meditation Centers Worldwide, delivered to the full assembly.

I went into a conference "moving meditation" exercise aware of its well-documented benefits for stress reduction. Stepping about in a circle at varying rhythms to recorded instrumental music (mainly zither, I think), my fellows and I became mindful of our connection with the floor. We sat for a guided meditation, focusing first on merely being, and then working toward a finer appreciation of nothingness. It was pretty relaxing. I got a little tense, though, when meditation leader Sam Kirschner brought the monism to the surface.

"From this place," Kirschner informed us, "you can authentically change your reality to whatever you want it to be."

The Dalai Lama—Not

Presiding over the conference was a mishmash of religious icons, including Buddhas and Hindu gods, with the biblical traditions represented by a candelabrum, a small statue of the Virgin Mary, and man-sized, bronze angels. They formed a kind of altar to multiculturalism.

Mollner invoked the all-inclusive, generic deity of this altar when he told groups preparing their mock 2012 board meetings, "People are connected with and inspired by the divine in a way that inspires all their choices."

The Dalai Lama had agreed to deliver a keynote address, organizers said, but illness forced him to cancel his scheduled trip to the United States. It would have been natural for him to attend. Since the mid-1990s, dozens of New Age-tinged conferences on spirituality in business and the workplace have cropped up from Canada to Australia—The Message Company's "Eighth International Conference on Business and Consciousness" took place in Santa Fe, New Mexico, just last month—but this one was higher in profile. It brought to the nation's financial nerve center the leading thinkers in the movement—Mollner, futurist John Renesch, and Canadian consultant/author Martin Rutte, among others—and representatives from global firms such as Honeywell, Hewlett-Packard, and American Express.

In his stead the Dalai Lama sent his special envoy, Lodi Gyari. In his plenary address, Gyari said he did not mind criticisms in the East that some lamas have been born—that is, reincarnated—into the commercial classes. "To be reborn as a businessperson is certainly not seen as a downgrade," Gyari assured the conference guests.

Peter Senge, senior lecturer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and author of the organizational theory classic The Fifth Discipline, addressed the conference. Historically, spirituality has been inseparable from religion, he said. Standing no more than 10 feet from the multicultural altar of world religions, he went on to say that a solution awaits this "profound problem—how we can disentangle the confines of religion from spirituality."

Senge had no complaint against the religious systems of "indigenous peoples," though. Indeed, his main challenge was, "What will it take to become indigenous?"

Maybe water can tell us, he continued, proceeding with an extended talk on the soothing effect that phrases like Love and Appreciation, taped onto glass jars, have on the molecular structure of the water within. The presentation included macro photographs of the starry water molecules in their bliss, as well as images of the disfiguring terror they apparently experienced after spending the night with messages of murderous threats or the name Adolph Hitler.

"What we think, what we feel, actually matters," Senge said. The point being: The elements are alive, in line with the Gaia hypothesis of Earth as a conscious organism. The subtext: Thus will the planet all the more readily comply with development and deployment of man's consciousness. Moreover, a conscious planet is all the more fit to be worshipped (if you're a neopagan) or to be one with the Universal All (if you're a New Ager).

Such pseudoscience meshes well with the metaphysical vision underlying New Paradigm business and underscores the peculiar gospel that Senge ultimately proclaimed: science (with help from business), rather than religion, will be the new institutional home for spirituality.

These kinds of philosophies lie behind some of the environmental concerns in New Paradigm business; a conscious planet surely calls for preservation. On the more practical side, Ben Cohen, cofounder of Ben & Jerry's Homemade Ice Cream Inc., gave a seminar on how business can benefit environment and community.

The new Ben & Jerry's flavor "Karamel Sutra" notwithstanding, Cohen typifies New Business leaders who may not adhere to all the exotic philosophies underlying the movement but are at the forefront of its overt goals: providing employees with values-based motives more than material incentives, caring for the environment, and honoring local and global stakeholders—vendors, customers, owners, and stockholders.

Ben & Jerry's was among the first companies to conduct a "social audit," measuring its effect on the local and world community. Employees report high job satisfaction because of the meaning they find in the "social mission" of the company. The South Burlington, Vermont-based firm encourages employees and customers to have fun and to serve others through company-sponsored social activism. It has poured a higher than average proportion of its profits back into the local community through charitable giving.

Asked about his spiritual influences, Cohen said growing up in a Jewish home instilled in him an empathy for the poor and oppressed.

"After that, a big influence was The Grateful Dead," Cohen said. "They have a lot of lyrics about spiritual values."

Fringe to Mainstream

Like Christians in business who have integrated their faith into their marketplace callings, those attending the Spirit in Business conference were well past the stage of joking that "business spirituality" is an oxymoron.

Christians have seen the emergence of 900 marketplace ministries in the past decade. Like them, the conference participants knew that business lies at the heart of a vast range of spiritual issues, including the quest to connect with a higher purpose.

In many ways, they are inadvertent allies to building biblical values into the workplace. Some of the movement's key tenets—such as bringing the "authentic" or "whole" self to work, rather than merely one's utility—have been stated in other terms by renowned Christian business leader Max De Pree, and before him by mainstream management icon Peter Drucker (also a Christian).

As early as 1954 Drucker wrote in The Practice of Management that firms can "hire only the whole man." The "Quality Circles" structure that Drucker and others pioneered have helped workers fulfill their potential by imbuing them with responsibility and creative outlets. Such corporate innovations dovetail nicely with New Paradigm tenets designed to boost human potential—as they do with biblical values that promote human dignity.

Most of the New Business values fit well into Christ's kingdom: love; honor; service and servant leadership; trust-based ("covenantal") relationships between manager and employee, rather than fear-based ones dependent on corporate hierarchy; community; environmental stewardship; creativity; cooperation; qualitative company assets like a sense of achievement; competence; ethical behavior; corporate higher purpose and responsibility; and personal fulfillment and development.

Not that the values espoused by New Paradigm business originated with it. Most had found their way into the mainstream long before the movement adopted them: Participative decision-making and servant leadership models that favor horizontal management structures, values-driven and people-first corporate philosophies, workplace wellness programs, and vision and mission statements. All emerged atop the tide of the past century's evolving management theory—itself often influenced by biblical values.

With this mixed bag of spirituality, it is difficult to say how much New Paradigm thought has "emerged" in the mainstream. Consultants at the conference noted that the hard-nosed business mainstream scorns some of their beliefs—for example, that profit is secondary to personal and community transformation as a company's raison d'être. Conference organizers acknowledged their failure to draw some high-profile executives still afraid to identify themselves with a movement regarded in important quarters as New Age fringe.

That an executive from the securities firm Goldman Sachs participated in the conference was significant, Spirit in Business president Andrew Ferguson told CT. "But I can't tell you how many top-level executive people I've talked to who would love to be here, but are not ready to do it in prime time," he said.

Sander Tideman, who described himself as an agent of the Dalai Lama, told CT he was an executive at a bank in Amsterdam but wouldn't reveal which one. "I'd rather not say, in this context," he said.

The conference visionaries believe they are caught up in the initial stages of a universal paradigm shift. As such, they do see their cause making steady progress. "Several years ago I would have said this kind of workplace spirituality was on the periphery," consultant and speaker Martin Rutte told CT. "I'd say it's on the periphery of the center now." Judi Neal, founder of the Association for Spirit in Work, estimates that at least 10 percent of management consultants include spiritual emphases.

How much New Age content seeps into the office along with the New Business values is also an open question. New Paradigm author John Renesch wondered how many conference participants saw the "metaphysical big picture" of the need to evolve spiritually.

"That was the question I came with," Renesch said in an interview. "Because if business doesn't change, the world is doomed—because business is leading the pack."

Recent corporate scandals and anti-globalization rants are signs that traditional business ("the Old Paradigm") is in decline as the New Paradigm is ascending, Renesch said. The term New Paradigm, though, is rarely used outside of the movement's thought leaders. "New Paradigm was too academic," he said. "It's probably going to get renamed."

New Business visionaries continue to grapple with appropriate language—including, perhaps, what to call that generic "higher power"—and it remains largely a movement without a name.

"I don't think we've got the language yet," Ferguson said. "And I don't think that hitting the business world with spirituality is going to do it."

Founding Visionary

The esoteric use of ordinary words like self-actualization, intuition, and visualization in the New Business spirituality (see "Utopia or Kingdom Come?" p. 36) cannot be appreciated without considering their role in the cosmic scheme of the movement's unofficial father: metaphysical futurist Willis Harman.

Harman, who died in 1997, founded the Institute of Noetic Sciences and helped start the World Business Academy. Noetic comes from the Greek word for intuitive knowing. Intuition was no mere "gut feeling" for Harman, but the very means of connecting to the one Universal Mind. Nor was visualization merely a means of clarifying goals, but of altering material reality.

Both intuition and visualization were central in the evolution of consciousness that Harman envisioned. Gathering the philosophical, scientific, and paranormal wisdom of the ages, Harman developed a metaphysical vision of the planet in which business, as the emerging dominant power, would play a central role.

Harman's vision fits, if not defines, the New Age tenet of mystical evolution—humanity's (markedly anti-Darwinian) spiritual progress toward a utopia of sharing and abundance; a common code word is transformation. While Renesch is reluctant to use utopia to describe the goal of New Paradigm business, a spiritually idyllic society is the hope and goal of faith in mystical evolution.

This ultimate destiny, in both New Business and New Age thought, requires a shift from rational thought to intuition. Cultivating this intuitive "inner wisdom" means doing away with "the belief in the limited extent of one's own ability to create what one wants," as Harman wrote.

A participant at the Spirit in Business conference hinted at her faith in this mystical evolution toward spiritual paradise. She exclaimed, as part of her seminar group's visualization of a corporate board meeting in 2012, "We are consciously metamorphosing!"

Awards Gala

The conference culminated in the bestowing of the first Willis Harman Spirit at Work Awards, which were also open to nonprofit organizations. London-based Body Shop International, Anita Roddick's values-driven, socially active company that supports local buyers and sells environment-friendly products, took first place "for the explicit embracing of spiritual principles." An East Coast rep for the Body Shop was on hand to accept the award.

John Renesch, a disciple of Harman, handed out the awards to seven organizations—including a few of Christian tradition. Houston-based Methodist Health Care System won fourth place for its "explicitly spiritual, nonsectarian charter. … and its appointment of a Vice President of Spiritual Care."

Catholic health care and housing organization Wheaton (Ill.) Franciscan Services Inc. took the seventh place award for creating a Spiritual Services Function department. The award also honored the nonprofit organization for the spiritual enrichment of its leaders at its annual retreat.

Before Renesch recognized the winning organizations, he paid homage to Harman. As he spoke, Neal of the Association for Spirit at Work stood with one arm raised and the other around Renesch.

"I wouldn't be doing anything in my life that I'm doing if not for him," Renesch said, pointing out that Harman cofounded the World Business Academy, that his Institute of Noetic Sciences had 60,000 members at one time, and that his Global Mind Change was still in print. "I still love him."

Vocation, or calling, is central to any spirituality of business, and perhaps Harman is as close as New Paradigm advocates get to a Caller. It was the former New Age Journal that, in a 1996 issue, suggested readers think of their work as a calling in order to "feel more fulfilled."

That suggestion—unmindful of the problem created when there is no distinction between the Caller and the called—reflects a spiritual yearning. Perhaps it is the yearning of a people who, with eternity set in their hearts, nevertheless cannot fathom their Creator (Ecc. 3:11).

As Christian theologies of vocation assert, the identity of the Caller is more important than the calling. Regent College's Stevens notes that Christians do best not to seek fulfillment in work but to find satisfaction in God through work, among other means.

"With absolute courtesy, Jesus comes to us in the workplace not to tell us what to do with our lives, but to ask what we are discovering in our search for meaning in our work," Stevens says. "And then, with infinite grace, he offers himself."

Jeff M. Sellers is an associate editor of Christianity Today.

Copyright © 2003 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere

Also appearing on our site today:

Utopia or Kingdom Come? | Discerning wheat from chaff in the new business spirituality.

Prosperity Consciousness | How the higher self gets down to business.

Organizations or conferences mentioned in the article include:

- Spirit in Business

- Institute of Noetic Sciences

- World Business Academy

- The Message Company

- Spirit at Work

- International Conference on Business and Consciousness

Scruples' online sites offer resources, articles, and web forums on spirituality in the workplace.

Marketplace Ministries exists to share God's love through chaplains in the workplace by on-site Employee Assistance Program for client companies.

In November 1999, BusinessWeek looked at the growing presence of spirituality in Corporate America in the article, "Religion in the Workplace."

Beliefnet.com has an archive of articles on spirituality and religion in business.