In this series

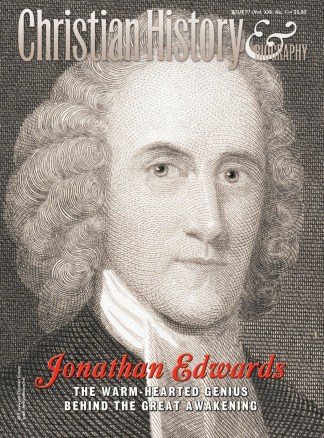

Puritanism had lost its vitality, and for years, the "friends of vital piety" had prayed for revival. Finally, in the late 1730s and early 1740s, a great spiritual dam seemed to break in New England. Streams of Christian conviction and conversion rushed through the land.

One historian has compared the emotional force of the Great Awakening to the radical furor of the 1960s, with its civil rights demonstrations, campus disturbances, and urban riots.

The new excitement and new ideals of the awakened brought with them controversy and divisiveness—much of it over the nature of religious experience.

The controversy is easy to understand. Some converts claimed new religious insight. Others erupted in emotional outbursts. Still others censured their pastors for lack of spiritual fervor. Even friends of the revival could see that not all the fruit of this new season came from the Spirit.

But how to distinguish genuine religious experience from counterfeit? The question haunted Jonathan Edwards as he pondered the meaning and results of the Awakening.

How do I know I'm saved?

Two short-lived revivals in his Northampton parish (1734-35, 1740-41) provided the laboratory for Edwards to observe what the Puritans had always called "experimental" (that is, experiential) religion.

For more than a decade, Edwards researched the fruits of revival. He publicized the results and his conclusions first in letters describing the revival in his own congregation, then in several sermons, and finally in his book-length treatise, Religious Affections (1746).

When the excitement had died down, Edwards emerged from this period with an insightful, biblically rooted scheme of evidences by which revival participants might discern the true meaning of their religious experiences.

Edwards did not want merely to describe the mental and spiritual state of the awakened. He sought to establish "signs" or indicators of those truly regenerated by the Spirit of God. Drawing from the Bible, traditional Puritan use of heart-language, and Calvin's notion of sensus suavitas—a sense of God's beauty, sweetness, or holiness that saints apprehend or taste—he developed a new psychology by which to understand the regenerating work of God's Spirit.

The revival laboratory

In "Faithful Narrative of the Surprising Work of God" (first written as a letter in 1735 and then published in 1737), Edwards chronicled the events that triggered the revival of 1734-35, including several deaths that seemed to impress locals with seriousness about the state of their own souls.

Then he described the unusual number of conversions that ensued and sketched the changes he observed in the lives of the converted. Outwardly, the saved abandoned old vices and contentious ways; inwardly, they testified to a new or "lively" sense of the divine presence and a new "disposition" toward religious things.

"More than 300 souls were savingly brought home to Christ," exulted Edwards.

Yet, several occurrences marred the orderly work of the Spirit. In a state of spiritual despondence, Edwards's uncle committed suicide. Two people in nearby towns went mad "with strange enthusiastic delusions." Others "[broke] forth into laughter, tears often at the same time issuing like a flood, and intermingling a loud weeping."

Despite these incidents, in his "Faithful Narrative" and his subsequent "Distinguishing Marks of a Work of the Spirit of God" (1741), Edwards defended the revival as God's work by demonstrating the authenticity of the conversions.

"In the main, there has been a great and marvelous work of conversion and sanctification among the people here," he reported.

He admitted there were irregularities and excesses but suggested heeding the advice of the writer of 1 John to "try the spirits whether they be of God" (4:1).

He proposed "signs" (both positive and negative) by which an experience might be judged legitimately the work of the Holy Spirit.

In "Some Thoughts Concerning the Present Revival of Religion in New England" (1742), Edwards expanded his discussion of "signs," calling the "fruit of the Spirit" in Galatians 5:22-23 (love, joy, peace, long-suffering, gentleness, etc.) "religious affections."

Holiness, Edwards argued, came from the heart (the center of both thinking and feeling) or the will, rather than the understanding. And holy or religious affections (again, emotions and the will) are the substance of genuine religion.

Edwards thus rejected the widely accepted "intellectualist" view that associated passions solely with the body (the untamed "animal nature"), over which the reason must triumph.

"He that has doctrinal knowledge and speculation only, without affection," he concluded, "never is engaged in the business of religion."

Between "Old Brick"and the radicals

In 1746, two years after he declared the revival over, Edwards published his Treatise Concerning Religious Affections. Here he attended systematically to the nature of revival and to religious experience generally.

The Religious Affections describes the spiritual character of the converted, those who grasp the beauty of God and delight in him. It is a taxonomy of the soul, classifying the perceptions, attitudes, and actions of the regenerate.

On one hand, the treatise shares the preoccupation of the eighteenth-century Enlightenment with scientific inquiry and empirical proof; on the other, it denies the Enlightenment confidence in the autonomous human intellect.

Edwards defends "true religion" against such critics of revival as Charles "Old Brick" Chauncy, the respected minister of the First Church in Boston. Chauncy denounced the revival as "enthusiasm" (literally, a mad belief that one is directly inspired by God). At the same time, Edwards countered enthusiastic radicals who took it too far.

The book's "sermon text" is 1 Peter 1:8—"Whom having not seen, ye love; in whom, though now ye see him not, yet believing, ye rejoice with joy unspeakable and full of glory" [KJV]. Edwards argues that when "full of glory," the believer's whole being is endued with a sight, a sense, and a power beyond nature—a supernatural sense beyond the five senses.

My affections, right or wrong

Drawing on English empirical philosopher John Locke (1632-1704), Edwards says that God created the soul or mind with two "faculties," intellect and will. While these faculties are interconnected, Edwards distinguishes between them in order to show the heart's priority in the believer's experience of God's saving work.

Intellect is the knowing or perceiving faculty, which Edwards calls "speculative knowledge." This involves assenting to "words" or "signs" without either approving or disapproving of them. For example, we may memorize a mathematical formula or the Ten Commandments, but the mere knowledge has no influence upon our motives or actions.

The faculty of will (or heart) not only "speculates and beholds," but also "relishes and feels." The most lively and intense operations of this heart-sense—the most "vigorous and sensible exercises"—are what Edwards calls the affections. These include love, hate, desire, joy, grief, and sorrow.

Some affections are morally and spiritually right. Some are wrong. Right affections incline the self away from self-interest and toward divine glory: "The Scriptures place religion very much in the affection of love, in love to God, and the Lord Jesus Christ, and love to the people of God, and to mankind."

Heart signs

Before considering signs of a true work of God, Edwards discusses twelve "no signs" that neither confirm nor deny the presence of the Spirit. Among them Edwards includes the immediate intensity of the religious experience, "bodily manifestations," extensive and fervent religious conversations, a devotion to religious practices, knowledge of Scripture, and even direct communication by God (for God spoke to the reprobate in Scripture). Though he calls these signs uncertain, he treats them as potentially good things in the life of the Christian.

Then Edwards turns to the twelve signs of a true Christian, all of which point to the glory of God. The first five highlight the divine source of the affections: they are wholly supernatural, "above nature," providing a new taste for divine things. Exercising that taste, the Christian loves God and Christ not for the benefits of peace, comfort, or eternal life—though these do come as by-products of salvation. Rather, the believer loves God for his own, intrinsic "beauty and sweetness."

Signs 6 through 11 focus on the character of the Christian. Edwards notes those who gave the appearance of change but then went back to their old, sinful ways.

Such people, says Edwards, are like a dirty pig that has been washed clean: the cleanliness is only temporary, for the pig will soon return to its pig nature—namely, its innate desire to wallow in the mud. Self-deceived hypocrites are like Ephraim of old, "a cake not turned," half roasted and half raw: there is no uniformity in their affections. Or they are like meteors that flare suddenly in a blaze of light but soon fall back to earth.

True saints are like fixed stars that shine brightly through time and space. They are humble, loving in spirit, spiritually hungry, self-reflective, and steady and abiding in their display of holy affections.

The "sign of signs"

The twelfth sign is "the chief sign of all the signs of grace," "the sign of signs, and evidences of evidences, that which seals and crowns all other signs." The true mark of a Christian is found in Christian practice or the outward display of love, for it is "the principal sign by which Christians are to judge, both of their own and others' sincerity of godliness."

Edwards dwells at length on this point: "Godliness in the heart has direct a relation to practice, as a fountain has to a stream, or as the luminous nature of the sun has to beams sent forth, or as life has to breathing." Holy action "is ten times more insisted as a note of true piety, throughout Scriptures … than anything else."

Religious practice lived out consistently amid the trials of life is also the most empirically verifiable religious affection. In the laboratory of Christian life, "the saints have the opportunity to see, by actual experience and trial, whether they have a heart to do the will of God, and to forsake other things for Christ, or no."

Though Edwards valued emotion as a sign that a person was truly doing the "business of religion," he refused to see true revival as a matter of experience divorced from the everyday expressions of love. A person can feel—or indeed talk, listen, sing, and pray—incessantly, but these will not promote religious renewal or give verifiable evidence of spiritual integrity unless accompanied by works of love and mercy.

Made weary by congregants who spent more time embroidering and broadcasting their testimonies than doing the work of the gospel, Edwards offered a piece of pointed advice: "We should get into the way of appearing lively in religion, more by being lively in the service of God and our generation, than by the liveliness and forwardness of our tongues."

David W. Kling is an associate professor in the department of religious studies at the University of Miami.

Copyright © 2003 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History magazine. Click here for reprint information on Christian History.