So from now on we regard no one from a worldly point of view. Though we once regarded Christ in this way, we do so no longer. Therefore, if anyone is in Christ, he is a new creation; the old has gone, the new has come! All this is from God, who reconciled us to himself through Christ and gave us the ministry of reconciliation.

Louie crew is the worst nightmare for many of my fellow conservatives in the Episcopal Church: he is an openly homosexual man, 65 years old, who often signs his Internet postings as “Quean Lutibelle of the Alabama Belles” and presses for changing the church’s policy on ordination and marriage. Crew and I could not be much further apart in what we think about sex and who we consider our theological kindred spirits.

Yet in the week before Thanksgiving last, as a nationwide battle for the White House disclosed anew some of the deepest cultural divisions in America—state by state and often county by county—Louie Crew and I sat working side by side in a basement meeting room of an Episcopal cathedral in South Bend, Indiana. For the first time since I met Crew nine years earlier, we worked toward a common goal as friends. In earlier years, we had developed a cautious respect for each other; we offered one another friendly words, both privately and publicly, but we had never really sat together, one on one, with our defenses down.

We were both participants in a meeting of the New Commandment Task Force (NCTF), a joint project of Crew and the theologically conservative Brian Cox, an Episcopal priest who has devoted much of his pastoral ministry to reconciling unlikely parties, whether in Africa, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, or the Midwest of the United States. Eighteen people—conservatives, liberals, and three moderates—had gathered at the Episcopal Cathedral of St. James in downtown South Bend for five days of sharply honest discussion about what divides us and what (if anything) might unite us. By the penultimate afternoon, I joined Crew to combine various people’s notes into a one-page public statement. We removed this piece of jargon and tweaked that sentence to describe what common ground we had discovered. We laughed together and complimented each other’s editorial choices.

This experience may not sound at all extraordinary, but it was. In retrospect, I also realize it was a milestone in my long, often subconscious search for the elusive quality of reconciliation.

Unlikely Allies

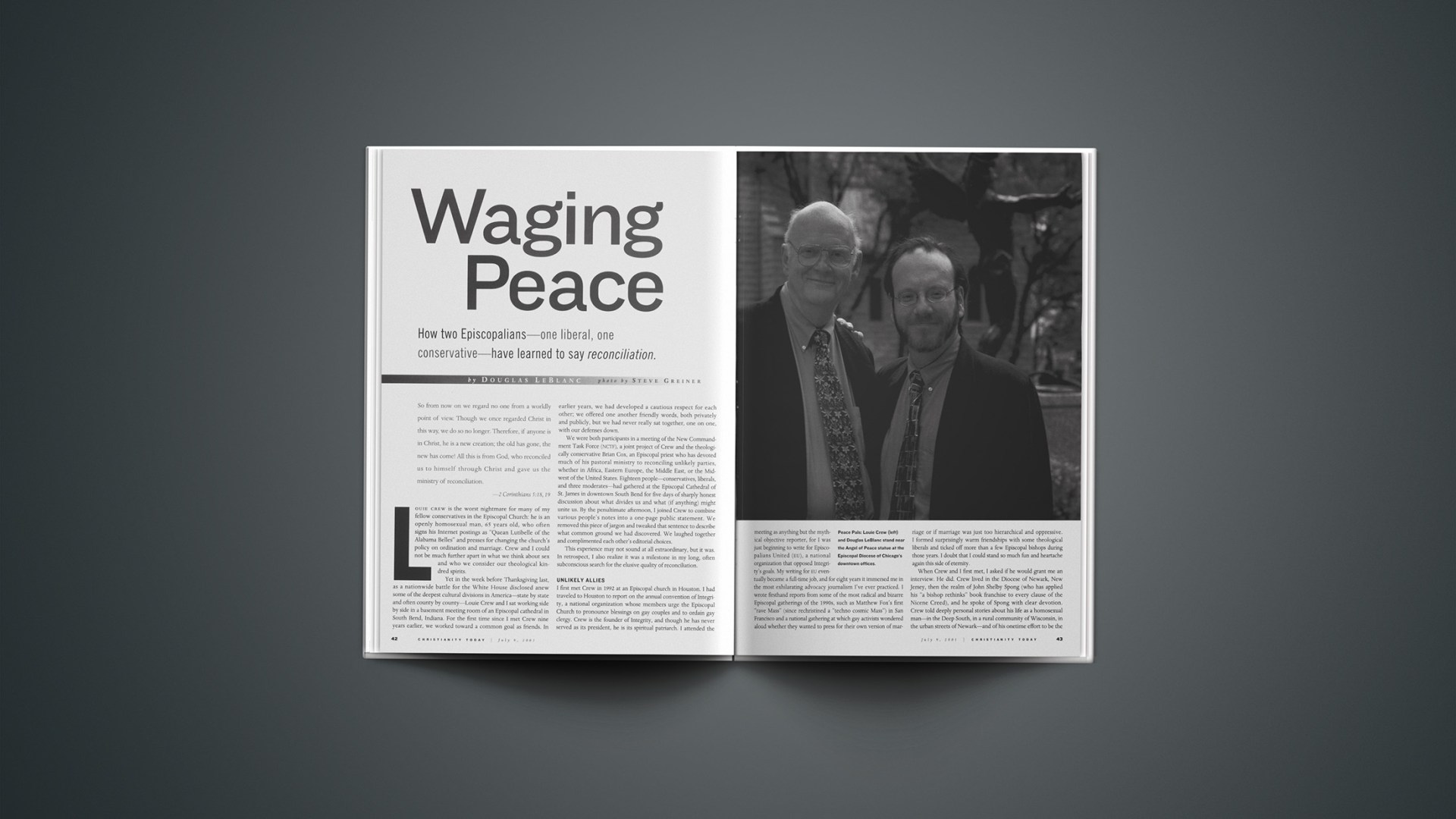

I first met Crew in 1992 at an Episcopal church in Houston. I had traveled to Houston to report on the annual convention of Integrity, a national organization whose members urge the Episcopal Church to pronounce blessings on gay couples and to ordain gay clergy. Crew is the founder of Integrity, and though he has never served as its president, he is its spiritual patriarch. I attended the meeting as anything but the mythical objective reporter, for I was just beginning to write for Episcopalians United (EU), a national organization that opposed Integrity’s goals. My writing for EU eventually became a full-time job, and for eight years it immersed me in the most exhilarating advocacy journalism I’ve ever practiced. I wrote firsthand reports from some of the most radical and bizarre Episcopal gatherings of the 1990s, such as Matthew Fox’s first “rave Mass” (since rechristined a “techno cosmic Mass”) in San Francisco and a national gathering at which gay activists wondered aloud whether they wanted to press for their own version of marriage or if marriage was just too hierarchical and oppressive. I formed surprisingly warm friendships with some theological liberals and ticked off more than a few Episcopal bishops during those years. I doubt that I could stand so much fun and heartache again this side of eternity.

When Crew and I first met, I asked if he would grant me an interview. He did. Crew lived in the Diocese of Newark, New Jersey, then the realm of John Shelby Spong (who has applied his “a bishop rethinks” book franchise to every clause of the Nicene Creed), and he spoke of Spong with clear devotion. Crew told deeply personal stories about his life as a homosexual man—in the Deep South, in a rural community of Wisconsin, in the urban streets of Newark—and of his onetime effort to be the husband in a heterosexual marriage. That marriage was not to last. (Crew now refers to a man named Ernest, his partner since 1974, as his husband.) I found this talented and charming nonconformist both fascinating and disorienting.

How much have Crew and I changed since we met in 1992? Have I come to agree with him about blessing gay couples? No. Has he changed his mind about sexuality or become any less an admirer of Bishop Spong? No. But primarily by listening not only to each other’s beliefs but to the reasons we hold those beliefs, we’ve learned to reach across the crevasse of our most profound differences.

This sometimes means sticking up for one another. I have challenged fellow conservatives who depict Crew as a libertine who would celebrate any and every sexual coupling engaged in by Episcopalians. Crew has publicly defended my work as a reporter when he had nothing to gain by doing it. I have tried to be a quiet peacemaker when my fellow conservatives clash with Crew. Crew once expressed his disappointment when my writing about Bishop Spong became too aggressive (I had included Spong’s every verbal pause for effect, and it was a cheap shot).

Suspicion and Skepticism

The New Commandment Task Force has met with an understandable skepticism, especially from conservatives. Frank Griswold, presiding bishop of the Episcopal Church, helped meet expenses for NCTF’s first four meetings, which only added to some conservatives’ suspicions. Conservative critics depicted NCTF as a gathering of theological quislings. (We all know the type of meeting: facilitators-for-hire forbid any appeals to Scripture; declare that every person has an equally true grasp of reality; write every spoken thought, however inane, on a Flip Chart; and imperiously give every person advance permission to “tend to your own comfort needs.”)

If NCTF had borne any resemblance to that picture, based on the real horrors of past dialogues mandated by the Episcopal Church’s national leaders, I would not have felt a moment’s interest in attending its session in South Bend. But in my waning months with EU, I came to know Cox as a priest who clearly affirms historic Christian orthodoxy in his own preaching and writing while striving to keep the Episcopal Church from arguing itself into irreversible division. Knowing and trusting Cox made me confident that an NCTF meeting would be what dialogue-by-fiat can only pretend to be. NCTF offered an honest discussion in which both sides are free to describe their most deeply held beliefs, and to risk the hurt feelings and righteous indignation that such candor usually produces. We’re still encouraged to use “I” statements and to listen respectfully, but appeals to Scripture are welcomed and debated.

In South Bend, for instance, liberals explained to conservatives why the phrase “gay lifestyle” is offensive to them (it implies a uniform pattern of behavior, presumably always debauched, for a wide variety of people). Conservatives explained why we find it so distressing to be described as Pharisees or as driven by presumptions that we “own Jesus.” Some conservatives spoke of feeling on the verge of leaving the Episcopal Church if its liberal moral and theological trajectories continue. Liberals spoke of feeling manipulated by conservatives’ talk of leaving, or by conservatives’ withholding money from our national church headquarters to protest liberal policies.

Behind my fellow conservatives’ strongest criticisms of NCTF are sincere and often unspoken questions: Is it possible to achieve reconciliation with the other side? Should we want to achieve it? And, most important, would God want us to achieve it? To put it in language that conservatives are more likely to use in private, what reconciliation can we achieve with sinners who will not repent and will not even agree that they should repent? I suspect that my liberal friends have similar conversations about conservatives. Is it possible to achieve reconciliation with (choose your adjective: homophobic, heterosexist, misogynist, medieval, Pharisaic, repressed) conservatives? Is that not giving comfort to the oppressor?

Divided by One Word

There both sides would stand, if we left it at that: questioning each other’s motives, assuming that only compromise and heresy can result by our talking with each other, and avoiding any discussion until the other side proves itself ready to repent.

Both sides ask honest questions about the other based on their understanding of the world and of God’s Word. Both sides believe they are challenging the other to live up to the standards of the gospel. But liberal and conservative Christians are often two people divided by one Bible.

Perhaps more precisely, we find ourselves divided by battling hermeneutics. Some liberals, such as author Bruce Bawer, have tried to explain our divisions as the church of law versus the church of love. You can guess which side plays the loathsome villain in that melodrama. Other liberals, such as Bishop Stephen Charleston of Episcopal Divinity School, claim that conservatives believe they “own Jesus.” Again, you can guess which side is better served by such language.

I have my own subjective theory: my side stresses the traditional narrative of Creation, Fall, and Redemption through Christ’s Atonement, while the other side stresses Original Blessing, a limited sense of the Fall, and a not-so-explicit Redemption through God’s all-inclusive love, with little mention of Atonement. I recognize there are exceptions to my generalization, and I hope future efforts at reconciliation will lead me to discussions with people who defy my assumptions. In the fullness of time, people on both sides will encounter God’s perfect truth, and we will understand with soul-shaking clarity whether we rightly discerned and obeyed his truth.

Meanwhile, some of us feel caught up into what liberal Anglican archbishop Rowan Williams of Wales has called “solidarities not of our own choosing.” I would put it more plainly as being stuck with each other, whether by God’s design or by our painful loyalties to a denomination that, despite its many failings, helped lead some of us to saving faith in the Lord Jesus. To state it directly, conservative Episcopalians have only a few options. We can:

Overcome our theological problems with Eastern Orthodoxy or Roman Catholicism and join either of those communions.

Move to another Protestant church that may be less sacramental in its theology or—a common experience—is already wrestling with the very same conflicts that cause us grief in the Episcopal Church.

Move to various bodies, such as the Reformed Episcopal Church, that have splintered off from the Episcopal Church.

I consider any of these choices not only viable but honorable, depending on one’s theological starting points. I rejoice for friends who find a greater sense of spiritual peace and shared mission in another church body. Nevertheless, some of us do not feel similarly called (or freed) by God to leave the Episcopal Church. I believe my loving quarrels with the Episcopal Church may never be finished.

More remarkable, especially compared to how I used to feel about being an Episcopalian, I have become thankful for the spiritual challenge provided by liberal Episcopalians. I often find their choices and priorities bewildering, but if I shielded myself from their presence, I would likely become complacent, smug, mentally and spiritually lazy.

Within the Episcopal Church, reconciliation is unlikely to mean either side changing much in its thinking. Reconciliation does not mean adopting a laissez-faire attitude toward those differences. Indeed, many of us as conservatives express our concerns for the harmful effects of our liberal counterparts’ moral and theological goals. We do not believe the church will be healthier or more conformed to the image of Jesus if liberals prevail on decisions regarding sexual morality. While those legislative decisions are still pending, however, and while the church engages in often anguished discussion about them, we are compelled to be in relationship with those fellow church members who so challenge the church to reconsider its historic teachings.

I recognize the inherent danger here of treating one’s own denomination as the entire measure of who is in proper unity and who has fallen into schism. Further, I know the anxieties of some conservatives that being in conversation with our moral and theological opponents in itself is an act of compromising the gospel. My primary reassurance about standing by the gospel is knowing that my fellow NCTF conservatives speak clearly about our understanding of the gospel when we meet across the table from liberals. Our friendships with them have not distorted our apprehension of Scripture’s clear voice on sexual morality, or on matters of Nicene significance.

I have doubts about how much we really accomplished in November 2000 at South Bend. Our group has not stayed in touch as it should, and one sharp conflict with another South Bend participant left me wondering if either of us had learned a thing. Nevertheless, I think that striving for reconciliation—and even failing in the effort—surpasses the cold comfort of gathering only with my like-minded brothers and sisters and clucking with satisfaction about how terrible the other side is.

Hearing One Another

Until the summer of 2000, I thought reconciliation might at best become an evergreen topic, something I would write about occasionally as a fairly detached observer. Brian Cox disrupted that low-cost plan when we saw each other at the Episcopal Church’s triennial General Convention, which is always the focus of much fear and loathing by activists at both ends of the theological spectrum. That year’s convention, as usual, did not fulfill the most apocalyptic fears of either side—some liberals feared the convention would lack the will to debate sexuality openly, much less cast any decisive votes; conservatives, as we have since the late 1980s, feared that this convention would cast the decisive vote on blessing gay couples.

Cox and I met early one morning after he suggested that God could be calling me into a work of reconciliation. Over coffee and a fast-food breakfast, the man who was once just another subject for a story challenged me to become more than just an observer.

That undertaking has only begun, but I feel that I’ve taken enough steps to apply the apostle Paul’s words at 2 Corinthians to my particular sense of calling.

I am involved in reconciliation work because I want liberal Episcopalians to experience my side of the discussion in terms other than fear and hatred, which seem to be their two most popular understandings of conservative Christians.

When these friends gather with other liberals and talk about conservatives, I want them to remember my kiss on their cheek.

I want them to remember the discussion when they helped me better understand what it’s like to fear for your safety because some thug on a bus has a finely tuned “gay radar.”

I want to remember that discussion when I’m with my conservative friends and talking about liberals.

I want them to remember how deeply it wounds conservatives to have our motives second-guessed.

I want to remember how deeply it wounds liberals to receive our written or verbal anathemas.

I want them to remember, and to feel in their bones, that conservatives do what we do because we love the Lord Jesus and we want to obey him.

I want to keep my eyes and my heart open to recognize when my liberal friends express the same motives.

When I first met Louie Crew in Houston, I was just beginning a course of trying to rescue our beloved Episcopal Church—it’s always beloved when we’re complaining—from people I considered theological interlopers and vandals. But it’s also impossible to cover people for nearly a decade without getting to know them and coming to care for them.

I’m no more in favor of blessing gay couples than I was in 1992, but I hope that by God’s grace I am a humbler representative of my convictions. I know that the street clothes of a peacemaker fit me better than the armor of a political activist.

Copyright © 2001 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

Related articles appearing on our site today include:

Identity-Based Conflicts | Father Brian Cox has preached reconciliation in Eastern Europe, Southern California, and now in his own denomination. (July 6, 2001)Getting Personal | Behind Douglas LeBlanc’s story of reconciliation in the Episcopal Church. (July 6, 2001)

The New Commandment Task Force site includes background information along with LeBlanc and Crew’s report from the 2000 South Bend meeting

Mainstream press coverage of Episcopalian liberal-conservative relations includes: The Post-Gazette,Seattle Times, andLos Angeles Times.

“I have seen the future of trendy ritual in the Episcopal Church, and its name is the Planetary Mass,” LeBlanc wrote in his analysis of Rave Masses for Episcopalians United.

Integrity’s official Web site includes Crew’s thoughts on founding Integrity, historical information and the quarterly magazine.

The Anglican Pages of Louie Crew include his projects, news and FAQ regarding “Quean Lutibelle.”

Anglican Voice has Brian Cox’s report on the Episcopal Church Reconciliation Initiative.

An outline of Brian Cox’s “Reconciliation Institute Basic Seminar” lays out the five-fold purpose of reconciliation.

Recent news articles on tensions within the Episcopal Church include:

Their truths shall set them apart | Citing biblical validity over unity, conservative Episcopalians boldly move toward a likely breakaway church. It’s a pattern as old as Christianity. — Los Angeles Times (June 30, 2001)Civil, religious courts mulled | Accokeek rector plans to file case against bishop, saying she broke church law — The Washington Times (June 30, 2001)Accokeek rector vows to stay despite Episcopal bishop’s suit | lawyer says he may ask denomination’s leaders to act — The Washington Post (June 29, 2001)Anglicans split over ‘illegal’ bishops | Anglican Mission in America controversy may have repercussions for the installation of the new Anglican Archbishop of Sydney — The Sydney Morning Herald (June 28, 2001)More priests a must | New bishop in AMiA sets priorities — Newsday (June 27, 2001)Episcopal bishop sues to regain control of parish | Dispute in Accokeek illustrates growing rift within denomination — The Sun, Baltimore (June 27, 2001)Rector challenges diocese, courts | Secular courts have no business ruling on church law, nor can they bar a minister from his pulpit, says lawyer for Accokeek priest — The Washington Times (June 27, 2001)A new thing in Denver | Oh, dear! It’s come to that: America as a mission field, in need of conversion. — Bill Murchison (June 26, 2001)Bishop sues to oust rector in Accokeek | Although several lawsuits have been filed recently seeking to prevent conservative Episcopal parishes from seceding, this filing marks the first time the church has gone to court to contest the appointment of a rector — The Washington Post (June 25, 2001)

For ongoing coverage, see Christianity Today’s Weblog and Classical Anglican Net News.