Self-taught Swedish artist Janeric Johansson has become a sort of itinerant diplomat. Johansson was born in 1950, and became a Christian in 1966 in a Pentecostal church, and now is a Baptist. He first exhibited in Copenhagen and Stockholm during the early 1970s. Various exhibits in Arab nations, Israel, New Zealand, Ireland, and Europe during the 1980s put the artist in contact with cultural officials from the Baltic states, Russia, and China.

Johansson’s compassion for those oppressed by their governments led him to develop graphic word concepts that had an intentionally challenging content.

These works will be featured in Work of Heart, a book scheduled for publication in Switzerland in the fall (and will be available through the Internet at www.janericjohansson.com).

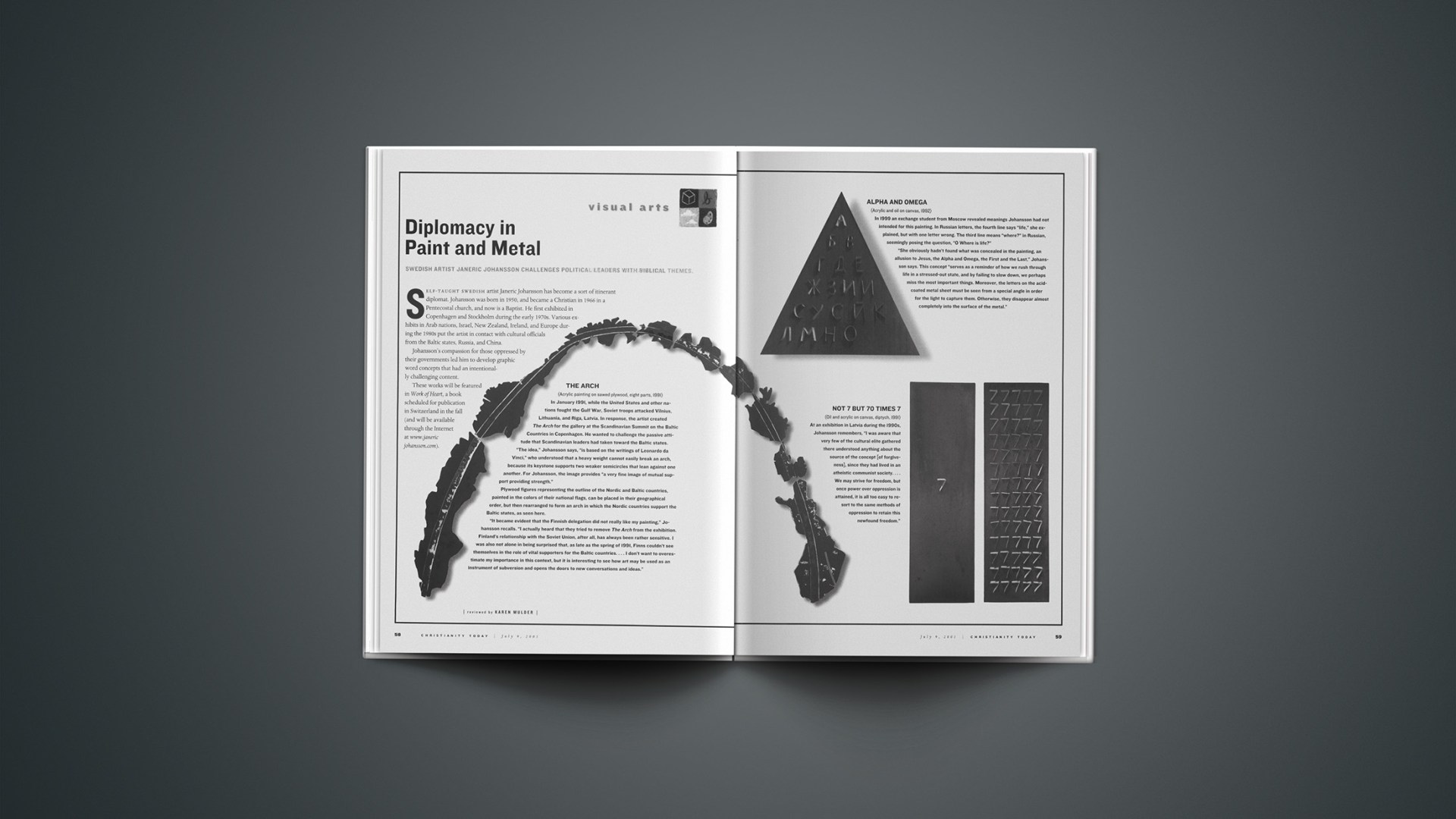

The Arch

(Acrylic painting on sawed plywood, eight parts, 1991)

In January 1991, while the United States and other nations fought the Gulf War, Soviet troops attacked Vilnius, Lithuania, and Riga, Latvia. In response, the artist created The Arch for the gallery at the Scandinavian Summit on the Baltic Countries in Copenhagen. He wanted to challenge the passive attitude that Scandinavian leaders had taken toward the Baltic states. “The idea,” Johansson says, “is based on the writings of Leonardo da Vinci,” who understood that a heavy weight cannot easily break an arch, because its keystone supports two weaker semicircles that lean against one another. For Johansson, the image provides “a very fine image of mutual support providing strength.”

Plywood figures representing the outline of the Nordic and Baltic countries, painted in the colors of their national flags, can be placed in their geographical order, but then rearranged to form an arch in which the Nordic countries support the Baltic states, as seen here.

“It became evident that the Finnish delegation did not really like my painting,” Johansson recalls. “I actually heard that they tried to remove The Arch from the exhibition. Finland’s relationship with the Soviet Union, after all, has always been rather sensitive. I was also not alone in being surprised that, as late as the spring of 1991, Finns couldn’t see themselves in the role of vital supporters for the Baltic countries. … I don’t want to overestimate my importance in this context, but it is interesting to see how art may be used as an instrument of subversion and opens the doors to new conversations and ideas.”

Alpha and Omega

(Acrylic and oil on canvas, 1992)

In 1999 an exchange student from Moscow revealed meanings Johansson had not intended for this painting. In Russian letters, the fourth line says “life,” she explained, but with one letter wrong. The third line means “where?” in Russian, seemingly posing the question, “O Where is life?”

“She obviously hadn’t found what was concealed in the painting, an allusion to Jesus, the Alpha and Omega, the First and the Last,” Johansson says. This concept “serves as a reminder of how we rush through life in a stressed-out state, and by failing to slow down, we perhaps miss the most important things. Moreover, the letters on the acid-coated metal sheet must be seen from a special angle in order for the light to capture them. Otherwise, they disappear almost completely into the surface of the metal.”

Not 7 but 70 Times 7

(Oil and acrylic on canvas, diptych, 1991)

At an exhibition in Latvia during the 1990s, Johansson remembers, “I was aware that very few of the cultural elite gathered there understood anything about the source of the concept [of forgiveness], since they had lived in an atheistic communist society. … We may strive for freedom, but once power over oppression is attained, it is all too easy to resort to the same methods of oppression to retain this newfound freedom.”

Copyright © 2001 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.